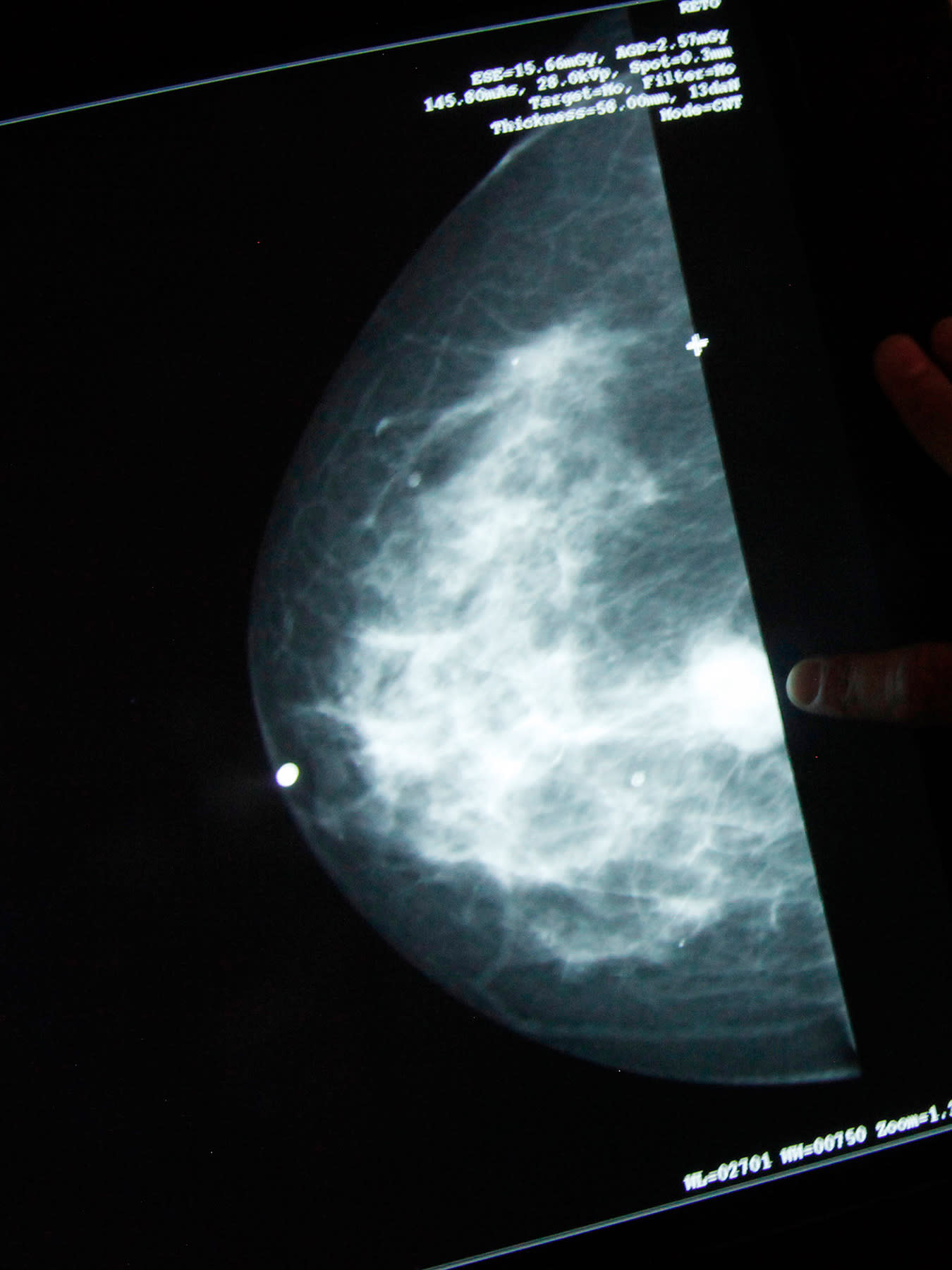

Annual mammogram screening delays in the current pandemic will only exacerbate the systemic race gap in breast cancer diagnoses for minority women in their forties. The fallout from COVID-19 (particularly in the Tri-State area) has restricted routine breast screenings and postponed biopsies and surgeries. These delays have left a backlog of people anxious about tackling their cancer at the earliest stages to maximize their chances of being cured. Pre-coronavirus, ethnic women in their forties had already been struggling with the unjust delays called for by the revised 2016 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) mammogram guidelines, which recommend skipping annual screenings altogether before the age of fifty, even though breast cancer diagnoses peak for Black, Hispanic, and Asian women in their forties.

Fails to account for ethnic differences in age-related breast cancer data

As a South Asian woman in her forties who was not high-risk and dodged breast cancer two years ago because of annual screenings, I object to the revised Task Force blanket recommendations, first published in 2016, for all average-risk groups to stop annual mammograms at age forty and to start biennially instead at age fifty. The new approach fails to account for ethnic differences in age-related breast cancer data for Black, Asian, and Hispanic women, while misapplying arguments about overdiagnosis, false positives, mortality, and cost to create fallacious perceptions.

There are four issues with the new recommendations worth highlighting in this essay.

Issue #1: Too Much Emphasis Placed on Avoiding Overdiagnosis

Autopsies occasionally discover unknown asymptomatic breast cancers that would never have affected a person's life or life expectancy, thereby insinuating that some cancers can be left untreated in a living person. Perhaps, a slow-growing cancer in a seventy-eight-year-old nearing the end of her life could reasonably go untreated.

Breast cancers in younger women often tend to be more aggressive

However, using autopsy findings to push screening delays is negligent for the younger forties age-group in which breast cancer diagnoses are more common among minorities, based on a major study by Harvard researchers. Although diagnoses amongst white women peak in the sixties, a significant 23 percent are still diagnosed under fifty. Moreover, breast cancers in younger women often tend to be more aggressive, making overdiagnosis a hollow argument as missing a potentially aggressive malignancy could have particularly devastating life expectancy consequences for this age group.

Issue #2: Using False Positives as a Reason to Defer Mammograms

False positives refer to suspected lesions in mammograms, which upon subsequent imaging or biopsies prove benign.

87 percent of all mammogram findings are accurate

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force states that false positives are a "principal harm" of mammography, insinuating that mammograms are not as valuable in the forties because they could be wrong. However in reality, 87 percent of all mammogram findings are accurate. Furthermore, 3D mammograms (tomosynthesis) comparatively produce 40 percent better detection, making them especially useful for women in the forties who may have dense breast tissue. Any exploratory imaging can only highlight potential areas to investigate. Although the Task Force emphasizes that diagnostic testing induces anxiety, it neglects to explain that this anxiety is fairly minimal compared to the subsequent stress endured by ignoring an area that turns out to be a pre-cancer or cancer. Minority women cannot be pacified through ignorance.

Issue #3: Overreliance on Mortality Data

By focusing on only mortality data, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines completely ignore quality of life improvement possible by catching an abnormality early enough to dodge harsher treatments, disfiguring surgeries, and debilitating side-effects that can chronically overwhelm patients, both emotionally and physically.

A woman enduring years of treatment for a later-stage cancer catch could theoretically live an equally long life as a peer who was diagnosed at an earlier stage and underwent less harsh treatment, but at what quality of life expense? Women in the forties are often in energetic roles as mothers, wives, workers, and community members. Ultimately, under the delayed screening guidelines, minority women of this age group will not only suffer greater mortality by being potentially diagnosed at a more advanced cancer stage, but also consequently endure a far lower quality of life while alive.

Issue #4: The Implication of Placing Health Care Cost Over Human Lives

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force claims that its final recommendations were made without cost considerations. Yet, the final Task Force modeling report intended "to help clinicians, employers, policymakers, and others make informed decisions about the provision of health care services," stated, "We compared model results for the twenty strategies to select the most efficient approach. In a decision analysis, we considered a new intervention more efficient than a comparison intervention if it results in gains in health outcomes, such as life-years gained or deaths averted, while consuming fewer resources (or costs)."

Eliminating such benefits would only raise the out-of-pocket costs shouldered by ethnic patients

This content has recently been removed from its website. However, the original cost intent can still be uncovered by reviewing a published U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement reiterating that the "most efficient" screening strategies were informed using a study from Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET), a consortium of top experts funded by the National Cancer Institute. The CISNET study explored twenty screening strategies; only those improving health outcomes "while consuming fewer resources (or costs)" were deemed "efficient." Separate studies confirm that U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations to delay mammograms by a decade will result in billions of dollars in savings. The new start at fifty guideline also potentially raises concerns about whether insurance companies will continue to offer annual mammograms at age forty as part of preventive care. Eliminating such benefits would only raise the out-of-pocket costs shouldered by ethnic patients.

Competing Recommendations Abound

Given this history, major physician groups and cancer organizations have fiercely disagreed with the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force on both its recommendation to start mammograms at the age of fifty and its goal to continue even those just biennially (every other year) for average-risk women. In fact, the National Consortium of Breast Centers, American Society of Breast Surgeons, American College of Radiology, and leading cancer institutions like Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York City and MD Anderson in Houston, Texas, all recommend mammograms start at forty and continue annually because new malignant tissue changes can often occur in just one year, even when there is no palpable lump. I was a case in point of a healthy woman in the 40–45 age bracket (with no genetic or lifestyle risk factors, and no lump), whose critical stage 0 pre-cancer was caught purely by my decision to pursue an annual screening approach, despite a normal mammogram the previous year.

One in eight women gets afflicted in her lifetime, and a 75 percent majority have no family history whatsoever

At stage 0, abnormal pre-cancer cells are unable to move or invade into surrounding tissue. Consequently, this stage is not reflected in true breast cancer (stages 1-4) statistics, which underscore that one in six true breast cancers actually do occur in the forties, one in eight women gets afflicted in her lifetime, and a 75 percent majority have no family history whatsoever. Nevertheless, stage 0 is arguably the most important early diagnosis opportunity to dodge the disease through the least harsh treatment options, including surgical routes that do not require subsequent chemotherapy, radiation, or long-term drugs. Through my journey, I learned that following the advice of major surgery, radiology and cancer treatment institutions to pursue mammograms annually in the forties is best, especially for racial ethnic women (Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians).

Therefore, annual mammogram literacy amongst minorities is crucial so that women in their forties are not blindsided by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force screening recommendations and can have more informed discussions with their own physicians about health choices. Before the pandemic, my efforts to increase awareness at multiple ethnic community centers revealed that only 48 percent of attendees realized malignant changes could even occur in a year. Following my seminar, 83 percent of them understood the importance of an annual mammogram for a healthy person with no family history, and 97 percent felt it was crucial to get diagnosed early at stage 0 (pre-cancer) to "dodge" stage 1 (invasive cancer cells in the breast).

These screenings and procedures cannot be tabled. They are not elective, and for minorities like me they never were.

Yet, the delayed screening approach during the current pandemic only compounds the systemic racial injustices in the Task Force guidelines. Since breast cancer diagnoses for white women peak in their sixties, a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advice to start mammograms at 50, deprives racial minorities (Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians) whose breast cancer diagnoses peak in the forties of that chance to become breast cancer "dodgers" rather than "survivors." Hence, as our nation prepares to reopen, a long-term strategy to ensure expanded health access for routine breast screenings, biopsies, and surgeries should be prioritized, so that a stronger second wave of COVID-19 does not undermine them again. These screenings and procedures cannot be tabled. They are not elective, and for minorities like me they never were.