Skyrocketing from 2 million views in 2021 to more than 1.2 billion in 2023, videos tagged #Ozempic on TikTok have flooded social media. This surge in attention has translated into soaring sales, making Ozempic one of the fastest-growing drug prescriptions of the century. Its effectiveness as a weight loss wonder drug, even though it is classed as a diabetes medication, has fueled incredible curiosity as celebrities continue to popularize its use, motivating adults to seek off-label prescriptions.

Behind the spectacle, however, drugs like Ozempic use natural hormones—such as glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs (GLP-1)—that are made in the gut. Older generation GLP-1 analogs (exenatide, dulaglutide) have existed for decades, but the newer ones have greater potency and have recently become a cornerstone of clinical practice for patients with obesity as well as with type 2 diabetes.

Because of new clinical shifts in provision, doctors are increasingly prescribing these medications to children and teens struggling with obesity. The use of GLP-1s in adolescents has increased by nearly 600% over the last five years. Given the rising prevalence of childhood obesity and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of these medications after the age of 12 in the United States, this trend of increased use is not surprising, but access and usage of these medications vary widely. Further, data on GLP-1 usage is limited internationally, and examining the global landscape for these drugs primarily highlights the scarcity of pediatric specific evidence and guidelines across countries.

How GLP-1 Drugs Are Used in Pediatric Weight Management

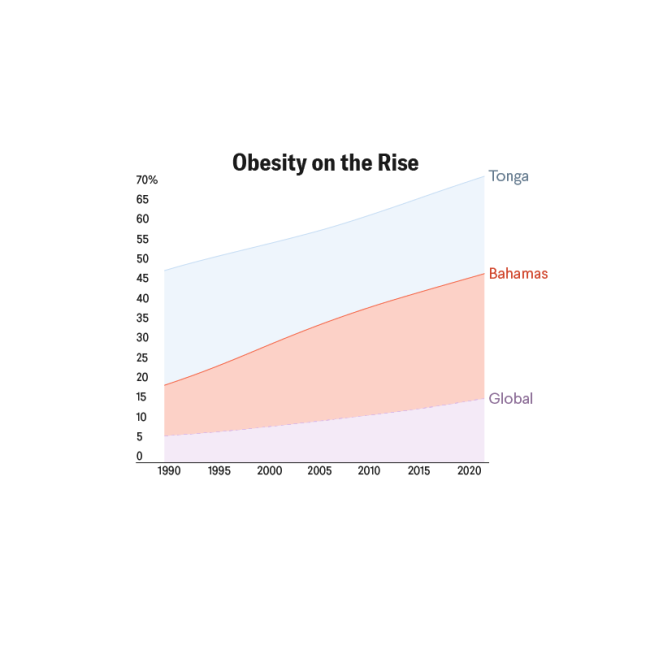

According to the Global Obesity Observatory, the United States has the tenth-highest obesity rate in the world. Care for chronic conditions such as obesity relies on the medical home: a concept of comprehensive and strategic coordination among multiple providers, such as weight management specialists, behavioral health experts, nutritionists, and primary care, to provide long-term care to patients as they transition from childhood to adolescence and adulthood.

Doctors are increasingly prescribing these medications to children and teens struggling with obesity

GLP-1s are becoming increasingly popular as first-choice medications for obesity—relative to other drugs such as metformin and Qsymia—because of changing patient preferences, differences in effectiveness, and the positive effects of GLP-1s on comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Yet many pediatricians do not prescribe drugs such as metformin and Qsymia directly to pediatric patients but instead refer them to weight management programs, pediatric obesity experts, or endocrinologists who can issue prescriptions.

Data showcases that children with obesity are five times more likely to have obesity in their adulthood than their healthy-weight counterparts. In previous years, pediatric providers treated obesity with only nutritional and behavioral changes. In 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released clinical guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with obesity, recommending the more prompt use of treatments previously considered intensive and thus restricted. The AAP now recommends that pediatricians offer medications or pharmacotherapy to patients 12 years and older with obesity, categorized as those with a body mass index (BMI) in the ninety-fifth percentile or above for their respective age and sex. AAP recommendations also refer patients 13 years and older with a BMI equal to or greater than 120% of this percentile with complications to bariatric surgery, which helps with weight loss by making the stomach smaller or rerouting the intestines.

Medication should not be the first course of action, and current evidence does not support its effectiveness as a sole form of treatment, nor do medical guidelines recommend such use. The AAP supports intensive health behavior and lifestyle treatment programs as the initial step for pediatric weight management, emphasizing more involved and frequent touchpoints with the treatment team.

With their strong focus on family involvement, these programs aim to foster behavioral modifications, health education, and skill-building over longer stretches of time, acknowledging that sustainable progress often requires consistent engagement. Thus these updated guidelines emphasize healthy eating, exercise, and lifestyle patterns that are durable and highlight the increased urgency to course-correct these patterns with thoughtful yet assertive action.

A Global Comparative Look at GLP-1 Use

As noted, research from the Journal of the American Medical Association reveals that GLP-1 prescriptions rose 594.4% between 2020 and 2023. Then, from 2023 to 2025, Wegovy (semaglutide) prescription rates rose 50%, from 9.9 per 100,000 adolescents in 2023 to 17.3 in 2025.

This U.S. trend does not mirror global GLP-1 uptake. Prescribing guidelines vary by country. The United Kingdom (UK) and the Netherlands have only approved GLP-1s for people with BMIs above 30 and 35, respectively. In the UK, a patient must also be reapproved for GLP-1 usage after every two years of prescription.

By contrast, in the United States, most insurance companies only approve GLP-1s for one year, despite its status as a long-term medication. The criteria for coverage in the United States vary greatly depending on BMI and comorbidities. For example, patients who are being prescribed GLP-1s are more likely to get coverage if they also have preexisting conditions such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and the like. This contrast highlights how regulatory bodies have often limited prescribing practices, even as clinical guidelines recognize efficacy across a wider range of individuals, including pediatric patients.

Some nations have released clinical guidelines on pediatric GLP-1 usage and prescription, including but not limited to the Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) as well as the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ). The IAP cites FDA approval guidelines for liraglutide and semaglutide for children 12 years and older in children with class 3 obesity of life-threatening comorbidities who have a BMI greater or equal to 40. The CMAJ recommends GLP-1 use in combination with behavioral and psychologic interventions in children 12 years and older.

However, even though adults are known to be using GLP-1s internationally, data characterizing pediatric usage is still limited, and pediatric data often trail the production of adult data. Thus less specific information regarding clinical trials and regulations from other nations is available. This situation underscores the need for further research to characterize global pediatric usage as well as the nuances of prescribing these medications across clinical contexts.

Conclusion

Despite the new AAP guidelines, important considerations remain about the broader usage of pharmacotherapy and challenges of weight management in children and adolescents. GLP-1 medications are a new dimension of opportunity and possibility for pediatric weight management. Being so powerful, GLP-1s, pharmacotherapy, and intense interventions surely have the potential to influence a child's social well-being, affecting peer relationships, self-esteem, and normal participation in typical social activities.

For starters, when children are started on GLP-1 medications early on in life, it opens the potential for their medication need to extend well into their adulthood. Teenagers, particularly those on the younger side (approximately 13 to 14 years old), may have difficulty fully understanding the long-term implications of initiating a prescription.

Furthermore, body image issues tend to be heightened during adolescence, making young people psychologically more vulnerable to weight-focused interventions. Because of this issue, it is important to strongly consider the psychosocial health of children when also considering initiating them on GLP-1 medications.

Last but not least, given the recency of these prescribing trends, no long-term data on the next-generation effects of these medications is available, leading to several uncertainties about the possibility and implications of long-term use. More research is therefore needed to better understand the safety and benefit GLP-1s offer to children and adolescents and to better understand their place in the broader continuum of weight management.