During a morning rush hour in early June, Deepali Mukhyadal received a phone call from her husband. Vicky, a 35-year-old police officer with the Mumbai railways, said he had completed his night shift and asked whether she needed anything from the market on his way home. Soon after, other police officers arrived at Deepali's doorstep.

Her husband, they said, had been injured in a train accident at Mumbra, a major suburban station on the Mumbai suburban railway network, and had been moved to their village for better treatment. When the homemaker and her 4-year-old son reached the village that afternoon, they learned that Vicky had sustained head injuries after falling off an overcrowded train and had died.

"He said he was coming home in 10 minutes," says 24-year-old Deepali, "All of a sudden, everything was over."

Vicky was one of 13 passengers who fell off the two trains on the morning of June 9, 2025—and one of the five who were killed. The accident took place when the trains, moving in opposite directions, crossed each other. Passengers, hanging off the footboards of the overcrowded trains, collided and fell off.

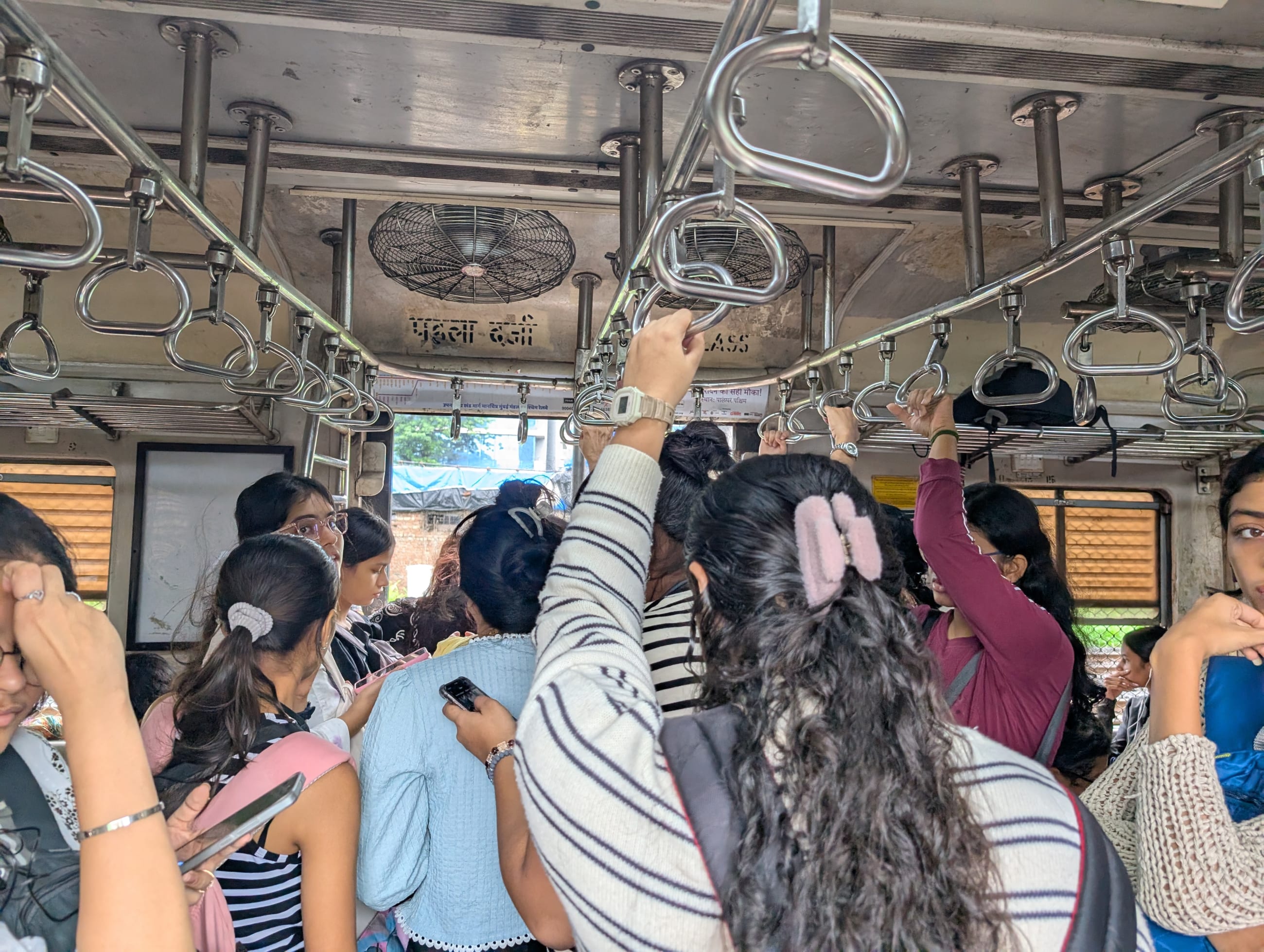

Between 2004 and 2024, Mumbai's trains claimed nearly 66,500 lives, and one of the primary causes was falling off overcrowded trains. Known as the city's "lifeline," Mumbai's suburban railway network carries 8 million passengers across the route's 400 kilometers every day—the busiest commuter railway network in the world. But the rail system is also one of the globe's deadliest, even as railway networks across South Asia report fatalities due to overcrowding.

The casualties continue to mount despite indictments by the courts and media, says A. K. Jain, a former commissioner for planning with the Delhi Development Authority, who authored a paper in 2013 for the United Nations about sustainable mobility in southern Asia [PDF]. "This is mainly due to lack of accountability, responsibility, reforms and new technologies for a more safe and sustainable public transit system," Jain says. "Comprehensive safety rules exist, but the problem lies in implementation."

The Accident

Twenty-four-year-old Akshay Sheravade was commuting to work on June 9 when the Mumbra accident occurred. He says that when the two trains crossed each other at a curve, his friend Aadesh Bhoir fell off and sustained fractures on his hand and leg. His train was overcrowded and both trains were moving at high speeds, he says, but the curve was particularly hazardous and caused one of the trains to tilt closer to the other one. "It's a weird curve. Similar incidents have been reported there before, but the government did not take any action," Sheravade says.

When people raise these issues, authorities ignore them—and now that this big incident has happened, they've sat up and taken notice

Lata Argade, chairperson of Federation of Railway Passenger's Association

Lata Argade, chairperson of the nonprofit Federation of Railway Passenger's Association, blames overcrowding for the accident, which forced passengers to hang off footboards. To manage congestion, Argade's organization has long campaigned with authorities to increase the frequency of train services and have automatic, self-closing doors installed in trains on the Central Line—one of three main railway lines on the Mumbai suburban railway network, where Mumbra is located.

The railways did launch air-conditioned trains with automatic doors in 2020, and 80 air-conditioned services now operate weekdays along the Central Line. Argade says, however, that these options cost six times more and remain unaffordable to many passengers. Citing the example of a one-way train journey between Mumbra and Mumbai's Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, Argade says that the fare for an air-conditioned train is 100 rupees ($1.10), much higher than the 15-rupee ($0.17) fare for a train without air conditioning.

"When people raise these issues, authorities ignore them—and now that this big incident has happened, they've sat up and taken notice," Argade adds.

Five months after the accident, official investigations blamed it on excessive train speed and the failure of two railway officials to repair a flood-damaged section of the track. The police also registered a case against these officials under statutes related to culpable homicide and committing an act that endangers life and personal safety of others. The accused officials, meanwhile, told the court that the accident occurred due to overcrowding. "Had the accident been caused due to the failure of the railways, then the tragedy should have happened with other trains as well since 200 trains pass through the same location," their lawyer argued.

The Policy Issues

After the Mumbra accident in June, the Bombay High Court expressed deep concern over the "alarming and disturbing situation" on Mumbai's suburban trains. It highlighted that in 2024 alone, 3,588 commuters were killed—an average of 10 deaths per day. To reduce fatalities, the court called for preventive steps such as installing automatic doors on local trains—a recommendation that a parliamentary committee had made eight years ago.

Similarly, in 2015, the Railway Board, the highest decision-making body of the Indian railways, had recommended that the number of coaches in Mumbai's trains be increased from 12 to 15. This would raise the capacity by 25% per train and help reduce accidents caused by overcrowding. A decade later, only 16 of the 258 trains in Mumbai have 15 cabins each. A $101 million project, destined to replace 12-coach trains with the 15-coach variety in one section of Mumbai's railway network, remains largely unimplemented seven years after Central Railways proposed the plan.

"The implementation delays are because the average commuter is a common citizen, a middle-class person whose life has no value," says Sameer Zaveri, a railway activist, who lost both his legs in a railway accident more than three decades ago. Zaveri has been filing public interest litigations to make Mumbai's trains safer since 2008. His legal successes have secured court orders to compel the government to deploy ambulances outside railway stations and build emergency medical rooms on platforms. More should be done to control overcrowding, he says.

"Every year, around 2,500 people fall off Mumbai's trains. About 700 of these succumb to their injuries; others are left permanently disabled. This is because the official seating capacity of a 12-coach train is 1,200, but during the peak hours, about 5,500 people travel in these trains," he states. "These deaths and injuries are preventable."

These deaths and injuries are preventable

Sameer Zaveri, railway activist

After the Bombay High Court came down heavily on railway authorities following the Mumbra accident, the government filed an affidavit in court, a copy of which Think Global Health obtained. In the affidavit, authorities admitted that falling off overcrowded trains was one of the major reasons for deaths on Mumbai's trains, and that they had implemented preventive measures such as knurling on grab poles to make them less slippery, adding additional grab handles, and asking more than 800 establishments to stagger office hours to reduce train ridership during peak rushes. The authorities stated that they were also in the process of implementing long-term structural upgrades, such as extending railway platforms to accommodate 15-car trains, further developing railway stations to ease congestion, and introducing capacity-enhancing upgrades across certain corridors.

However, various factors could impede the projects, the government stated in its affidavit, such as slow construction during monsoon seasons, land acquisition barriers, encroachment issues, and high traffic volume that restricted daytime work.

Overcrowded Trains Across South Asia

Other South Asian nations also face safety dilemmas because of overcrowded trains. In Bangladesh, commuters falling off the rooftops of overcrowded trains is a common occurrence. According to Bangladesh's railway police, an average of three people were killed in railway-related accidents every day in the past decade, and one of the major reasons for these deaths was falling off train rooftops. Further, in 2019, passengers in Bangladesh blamed a major derailment on overcrowding, which killed four and injured 67.

Sri Lanka, too, has reported instances of commuters falling to their deaths from overcrowded trains; in Pakistan, overcrowding is often cited as the underlying cause for major train accidents, including fires.

"The situation is nowhere as bad as Mumbai," Zaveri says. "The numbers of deaths and injuries that we see here . . . no other railway network is as dangerous."

Following the Mumbra accident, the government announced newly designed trains, expected to be rolled out by January 2026. Among their new features, the coaches will have vestibules so that passengers can move from one coach to another and balance out the crowd. For some commuters, these measures are too late.

Rehan Sheikh, a 25-year-old auto rickshaw driver, is another passenger who fell off the train on June 9. He wasn't standing on the footboard, he says, but a falling commuter grabbed his T-shirt for support, throwing Sheikh to the tracks, too. The next thing he remembers is awaking in a hospital with three bones broken in his right hand and injuries on his legs that keep him from walking for more than a few minutes at a time.

"I'd earn around 600 rupees ($6.78) from driving my auto rickshaw daily. But since that day, I haven't earned a rupee," says Sheikh, the only breadwinner in his family. "None of this was my fault."