This summer in Washington, DC, President Donald Trump deployed federal forces to address purported crime and disorder, including by clearing encampments of unhoused people in parks near tourist areas. These abrupt sweeps have not followed encampment resolution best practices, such as giving adequate notice, ensuring that appropriate housing options are available, and storing people's belongings.

Although local service providers have tried to secure shelter and hotel rooms, many unhoused individuals have simply been dispersed to nearby areas, likely losing belongings such as identification cards, access to survival spaces, and connections to social services. Multiple cities now brace for similar purges in the wake of an executive order signed in July that supports the removal of encampments.

Such sweeps hinder people's ability to go to medical appointments, destroy medications and equipment such as walkers and wheelchairs, and expose people with limited ability to protect themselves from the elements. The unhoused must constantly move and often endure sleep deprivation. Further, such forced displacement interrupts treatment for those with mental health issues, including substance misuse. These challenges accumulate to worsen the health of the unsheltered and can contribute to expedited deaths.

These actions risk making more people vulnerable to becoming unhoused as they attempt to access underfunded medical facilities and are faced with a growingly hostile housing market

These misguided sweeps are coupled with the Trump administration's larger plan to dismantle Housing First, an initiative prioritizing rapid placement in permanent housing for those in need, as the main approach to addressing homelessness by reducing funding overall (including ending the Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS program) and redirecting it from subsidized housing to shelters and compulsory treatment. The passage of Trump's so-called One Big Beautiful Bill could result in more people's losing health insurance, driving up medical debt, and causing many to be severed from disability benefits due to work and reporting requirements. These actions risk making more people vulnerable to becoming unhoused as they attempt to access underfunded medical facilities and are faced with a growingly hostile housing market.

Such a two-pronged approach goes against decades of research demonstrating that subsidized housing has been successful in reducing homelessness, most notably among prioritized groups such as veterans, and threatens to make a larger population susceptible to unsheltered homelessness, sweeps, and involuntary treatment.

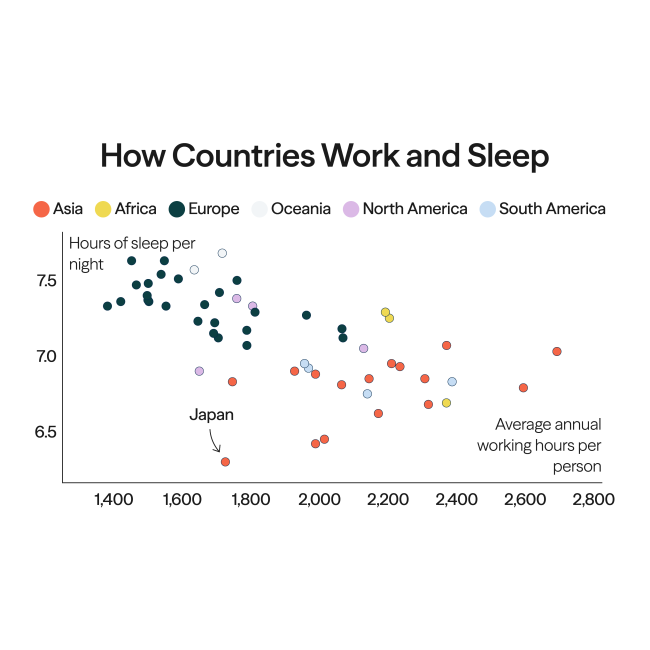

As opposed to these harmful tactics, examples from other regions could provide guidelines for implementing needs-based, holistic public assistance programs that can be delivered efficiently and help people escape homelessness in a durable fashion. Over the past two decades, Japan has used such an approach to achieve a remarkable 90% reduction in unsheltered homelessness [PDF].

Housing First

On a visit to Japan in 2019 during President Trump's first term, then-Fox News host Tucker Carlson interviewed him. They juxtaposed the cleanliness and lack of signs of unsheltered homelessness on the streets of Tokyo and Osaka with cities in the United States, especially those led by Democrats. President Trump asserted that he would end homelessness in U.S. cities, but did not reflect on how cities in Japan had achieved such low levels of visible homelessness.

By 2000, Japan's prolonged economic stagnation had generated encampments of thousands of people, mostly men who had worked in construction and manufacturing, living in plywood and blue-tarp huts in all major parks of Tokyo and Osaka. Rather than proceed with sweeps, one large-scale housing-first initiative in Tokyo called the Moving to Community Living Project [PDF] moved nearly 2,000 people from parks directly into apartments between 2004 and 2009.

Social workers set up mobile offices in parks and, over time, engaged with unhoused residents to help them move directly into subsidized master-leased apartments for which they only paid 3,000 yen (about $30 at the time) per month for two years. All residents were given a health screening and provided the opportunity to enroll in the national health insurance program.

People capable of work were provided with part-time public employment and job search assistance in the initial six months. Those who could not find work were enrolled in Japan's public assistance program, which provided a housing subsidy. About 80% to 90% remained in housing in the years after placement. In general, those who did not take the initial offer for housing were not forcibly removed. A few did stay in tents and huts along the Sumida River for years afterward but eventually moved into subsidized housing.

The general U.S. population is 2.7 times larger than Japan's, but the U.S. unsheltered population is 100 times larger

Government leaders expanded the concepts behind this project, namely, the use of public assistance, into a national effort that has produced impressive results.

In January 2025, the Japanese government counted 2,591 people living outdoors nationally [PDF], down from the peak of 25,296 in 2003 [PDF]. In contrast, in the United States, 273,224 people were counted as unsheltered in 2024 [PDF], a number that has been consistently increasing since 2015.

The general U.S. population is 2.7 times larger than Japan's, but the U.S. unsheltered population is 100 times larger.

What Has Made the Difference?

One key factor is the role of public assistance systems. Three features of Japan's Seikatsu Hogo (Livelihood Protection) system—generality, comprehensiveness, and expeditiousness [PDF]—seem to be contributing to the reduction of street-level homelessness. To understand how these features operate, a comparison can be made with the public assistance program for elderly and disabled adults in the United States. Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is the default program for low-income people who are ineligible for traditional social security benefits.

Generality refers to Livelihood Protection's targeting of all those in need rather than narrow categories as in the United States. The system is designed so that anyone under a certain income level can receive it. The concept of homelessness refers to a condition and those pushed into it are a diverse group. So, if the system is designed according to categories, as is the case with public assistance in the United States, some people risk being left behind.

The eligibility requirements under SSI detail that a person must either be 65 years old or older or have a disability as defined by the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA). However, claims of disability must be professionally documented, which can be difficult while living on the streets. Acceptance rates have been improved through SSI Outreach, Access, and Recovery (SOAR), a federal program to facilitate access to benefits among unhoused people. Yet between 2007 and 2017, the allowance rate for the unhoused was 45.8%, still about 10% lower than the rate for all applicants. These categories thus fail to encapsulate everyone who could be in need.

The comprehensiveness of Japan's Livelihood Protection works by combining various types of assistance that address multiple aspects of poverty in addition to living expenses. When a person without housing receives Livelihood Protection, they automatically gain access to housing assistance as well as Japan's national health-care system.

By contrast, SSI offers cash benefits, which have not kept pace with rising housing costs, and no rental assistance, leaving some recipients forced to remain homeless. The maximum SSI benefit amount is $967 for a single person, less than half of the fair market rent for a studio apartment in many urban areas. Making housing subsidies automatically available to all SSI recipients would have a dramatic influence on street homelessness. SSI approval does enroll people in Medicaid, a program that helps pay medical costs for low-income individuals, but not in all states, and without housing assistance, navigating a complex health system while living vulnerably on the streets or by the rigid rules of shelters could be overwhelming.

The expeditiousness of Livelihood Protection means that the time from application to adjudication is extremely short. By law in Japan, officials must rule on applications within 30 days, but the norm is within 14 days. Also, because the only requirement for receiving welfare is financial, in only a few cases is an application not approved if the applicant is experiencing homelessness.

According to data published by the SSA, the average number of days between when an applicant applies for SSI and the adjudication was 231 days in 2024—and rising because of staffing shortages. Rejections of SSI applications are also common, but people can appeal within 60 days. However, the average number of days it takes to adjudicate that reconsideration was 213 in 2023—a total period of more than a year (444 days).

In our interviews with people living unsheltered in the United States, we found that eligible people often do not receive SSI smoothly and some are incarcerated for minor offenses, often derailing the application process. Because shelters are full in most American cities, such delays in receiving benefits force many unhoused people to suffer the negative health impacts of unsheltered homelessness and criminalization. One interviewee in Los Angeles had her SSI application rejected four times before it was eventually approved. For years while waiting on the streets and in shelters, she endured traumatic street violence, arrests, debilitating sciatica, and worsening bipolar disorder and addiction.

Japan's reduction of street homelessness has also been aided by other factors, among them the absence of an opioid epidemic, a high level of institutionalization of people with severe mental illness, and a much more friendly rental housing market.

Despite the benefits, Japan's Livelihood Protection is not perfect. The uptake rate is low, around 20%, given the family support inquiries to relatives made at application and the refusal of some welfare offices to accept applications for arbitrary reasons. In addition, when a person without housing receives Livelihood Protection, admission to a facility is given priority over a private apartment, especially in large cities such as Tokyo. Some facilities have such poor conditions that they are referred to as poverty businesses that take recipients' cash benefits and housing subsidies but provide meager, if any, social services.

Despite these shortcomings, the Japanese welfare system has advantages over the American system, especially in terms of reducing unsheltered homelessness by providing quick access to rental assistance. Rather than investing in sweeps and cutting funding for subsidized housing, President Trump could better reduce unsheltered homelessness by paying more attention to addressing the limits of the public assistance system in the United States.