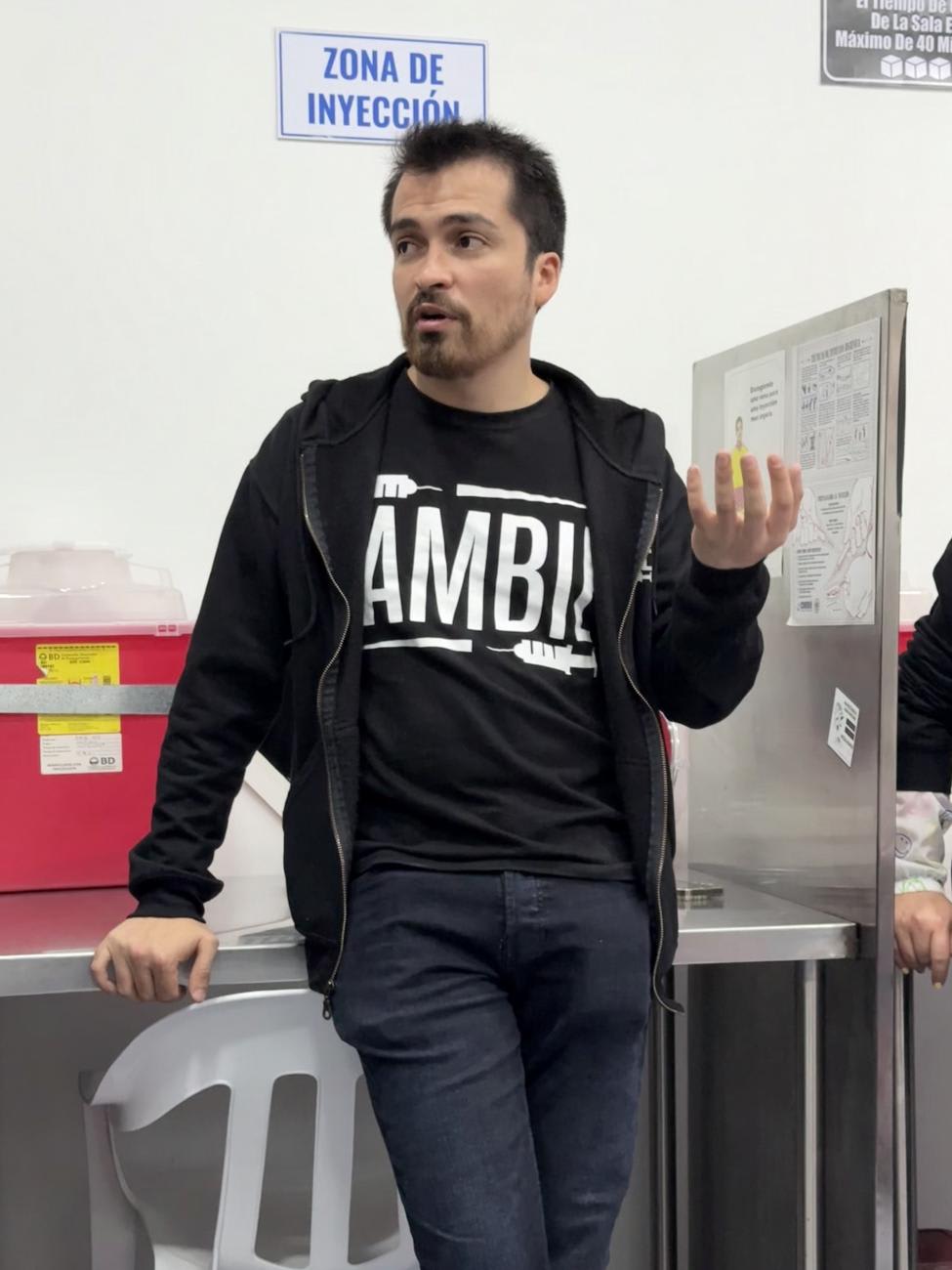

David Moreno has worked in social services for more than a decade, but he especially loves his role at Cambie—the first officially sanctioned safe injection site in Latin America.

Located in the Santa Fe neighborhood of Bogota, Colombia, Cambie has had to overcome all the criticisms typical for harm reduction facilities that provide a place to use illicit drugs under trained supervision. Most governments haven't sanctioned safe injection sites, also known as overdose prevention centers or supervised consumption sites, because of the prohibited substances and claims that the facilities attract crime.

Drug policy is contentious in Colombia, which produces the majority of the world's cocaine supply. The nation's overdoses increased by 356% between 2020 and 2021, from 8.5 incidents per 100,000 people to 40.5. This tragedy motivated the Colombian government to change its approach to overdose prevention and launch the 2023 National Drug Policy, which prioritizes health and well-being over criminalization.

Research shows that safe injection sites lessen public drug use and syringe litter, that they do not increase violent crime or drug use, and that they can dramatically reduce overdose deaths [PDF] as well as hepatitis and HIV rates in the surrounding community. Safe injection sites can even lead more clients to enroll in addiction treatment [PDF].

Safe injection sites can even lead more clients to enroll in addiction treatment

Moreno, who has used drugs himself, understands the stigma around addiction. That's why, when he approaches people in the neighborhood who inject drugs, the first thing he offers is a hug. "Many of them are transgender," he says, adding that they're often treated with ridicule rather than kindness.

Once Cambie launched in June 2023, its staff had one final group of people to convince—its prospective clients. Moreno says that respect is the most valuable part of his approach when he goes to inform people about Cambie's services. The site has registered 87 users from the local community in its first two years of operation.

Compared with other harm reduction facilities, such as needle exchanges, official safe injection sites are rare around the globe—only some 200 have been established. Yet they learn from one another.

Corporación Viviendo, a harm reduction organization in Cali, in southwest Colombia, opened the second safe injection site in the country on July 1. Its executive director Raúl Felix Tovar Beltrán says Cambie is "daring, brave and also clear in their concepts and methods."

Cambie's Creation

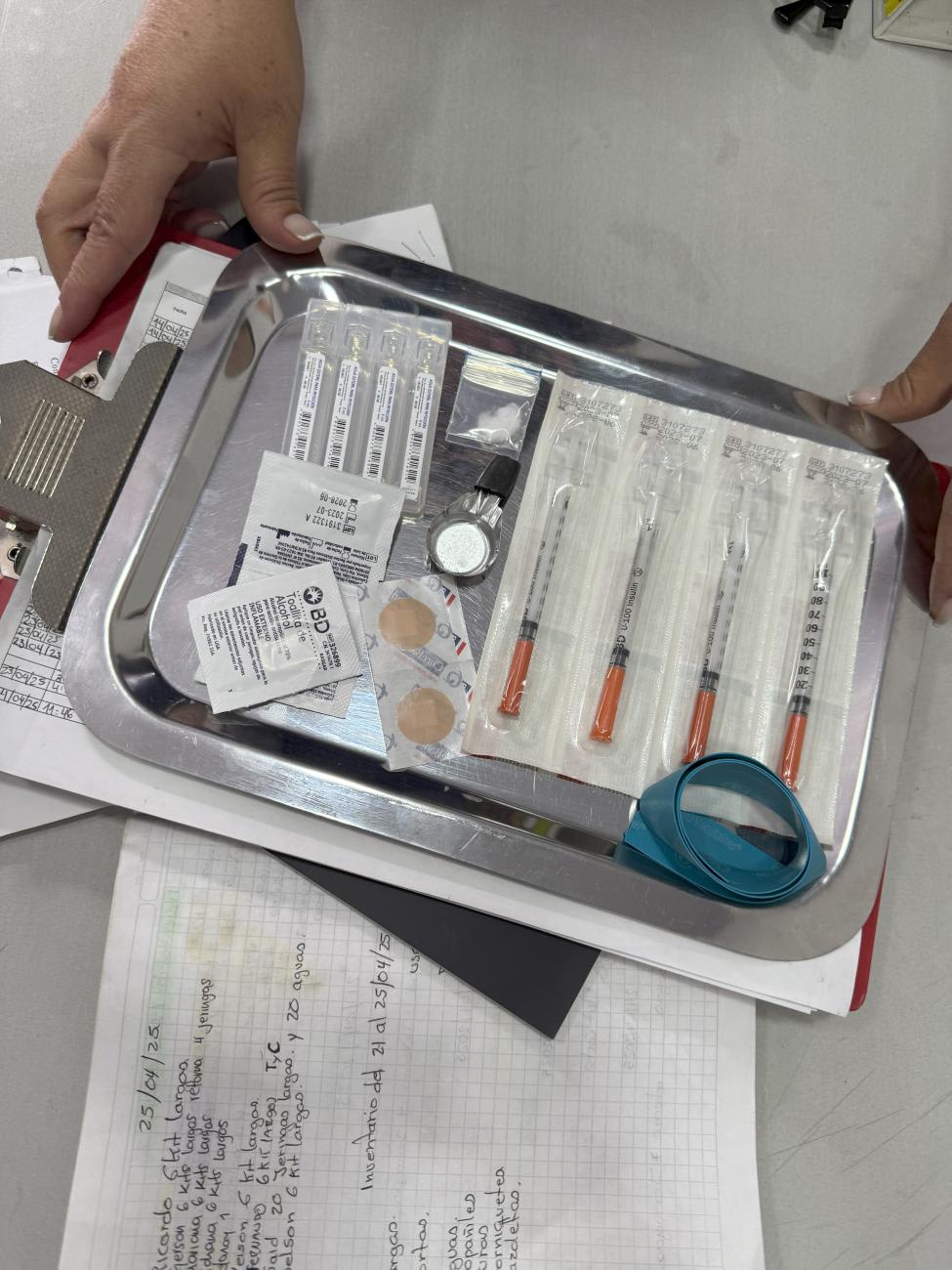

Cambie relies on two principles: prioritizing community buy-in and trust, and meticulous data collection. Daniel Rojas, a psychologist and Cambie's coordinator, developed a tracking system for drug usage. Each client is assigned an anonymized code, and every time they come in to use Cambie's services, they fill out a questionnaire about their recent drug use. What was the last substance you took? How did you take it? How many needles did you use? Where on your body did you inject? Cambie staff use this information to aid clients by identifying the safest dosage or most secure place on the body to inject.

As Rojas deploys this data-backed approach, Moreno tries to calm their state of mind so they are less likely to miss a vein. Clients are often anxious when they arrive, Moreno says, in particular if they're new. So he'll speak in relaxing tones and tell them to take deep breaths. He guides clients as they look at provided mirrors, allowing them to inject with more accuracy.

Rojas is also researching ways to avoid injections altogether. Using needles increases health risk for HIV, hepatitis, and other infections. He conducted a small pilot trial with 10 clients, offering a hammer pipe to smoke heroin rather than their usual tinfoil. Many heroin users opt to inject so that they don't waste any of their supply—because smoking from tinfoil means that much of the heroin could blow away in the wind.

Made with heat-resistant glass, the hammer pipes maintain a consistent flame and are constructed to maximize the amount of product inhaled. According to Rojas, the pipes led his clients to inject less, mirroring past research on the devices.

Julian Santaella Tenorio, a professor of public health at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Cali, received a recent grant to evaluate Colombia's safe injections site—and says that building trust with the local community before opening can help sustain overdose prevention work and make it more effective.

"When you see these more medicalized models in, for example, some places in Europe, it lacks that vibe of the community," he says, citing how Cambie's health workers go out into the neighborhood to prevent overdoses as well. "It permeates the community in a much broader way. So the impact is bigger."

Plans for Expansion

Corporación Viviendo's team is learning from Cambie how to approach small details, including precautions to take with health authorities, as well as practical aspects such as how to set up the injection room and what materials to use. According to Beltrán, in their first week of operation, people used the room 72 times.

"People who have used the room—and those who were initially hesitant—have highlighted the bonds with the team as a fundamental reason for coming and returning. They value the respect, trust, warmth . . . and coffee with something to eat," Beltrán says.

Workers at Cambie and Corporación Viviendo have yet to encounter fentanyl or other synthetic opioids in their drug supply—their drug-checking services have detected only heroin.

During its first year in operation, Cambie prevented every fatal overdose in the community it served. According to its annual report, Cambie reversed 14 incidents, all of which involved heroin. Ten were reversed within Cambie's safe injection facility, and four occurred nearby; clients reported these overdoses to the Cambie team. According to a translation of the annual report, "The main factors identified that lead to overdose in program users are dose escalation, lack of awareness of the dosage, use after periods of abstinence, and concomitant use with other depressants."

In the days before opening Corporación Viviendo in the Sucre neighborhood of Cali, Beltrán says four heroin users died—one of overdose in a public space and three of untreated illnesses. "This reality reminds us that our initiatives can make the difference between life and death," Beltrán says.

Rojas says Cambie's protocol has limitations. He always gets permission from clients to request an ambulance if they overdose, but so far, the ambulance has never arrived after a call to emergency services.

Bétran says that Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Brazil, Bolivia, Peru are all consulting with Colombian harm reduction organizations for lessons on how to open their own safe injection sites.