Wandering through the old hutongs of central Beijing during the months of February and March, one noticed a security guard and volunteer at every newly-gated alley entrance, making sure everyone coming and going is "on the list." At the village level, local committee leaders have gone door-to-door telling residents not to return to cities after Chinese New Year. Village residents have sometimes awoken to find the only road in and out of their town is blocked and guarded by local volunteers.

These are all pieces of evidence that we are entering a world that has completely changed.

Village residents have sometimes awoken to find the only road in and out of their town is blocked and guarded by local volunteers

In residential blocks, the meager authority of the "residential management committee" members has ballooned. At the beginning of the crisis, to avoid residents hitting the streets to shop and horde masks that were in short supply, these local leaders acted as distributors, rationing out masks, and enforcing movement restrictions. And the emergency paint bucket brigades have been at work, everywhere—demarking public life in evenly spaced increments. At the entrance to every park, subway, or similar public area, there are newly painted lines roughly six feet apart, reminding people to stay apart as they wait to enter.

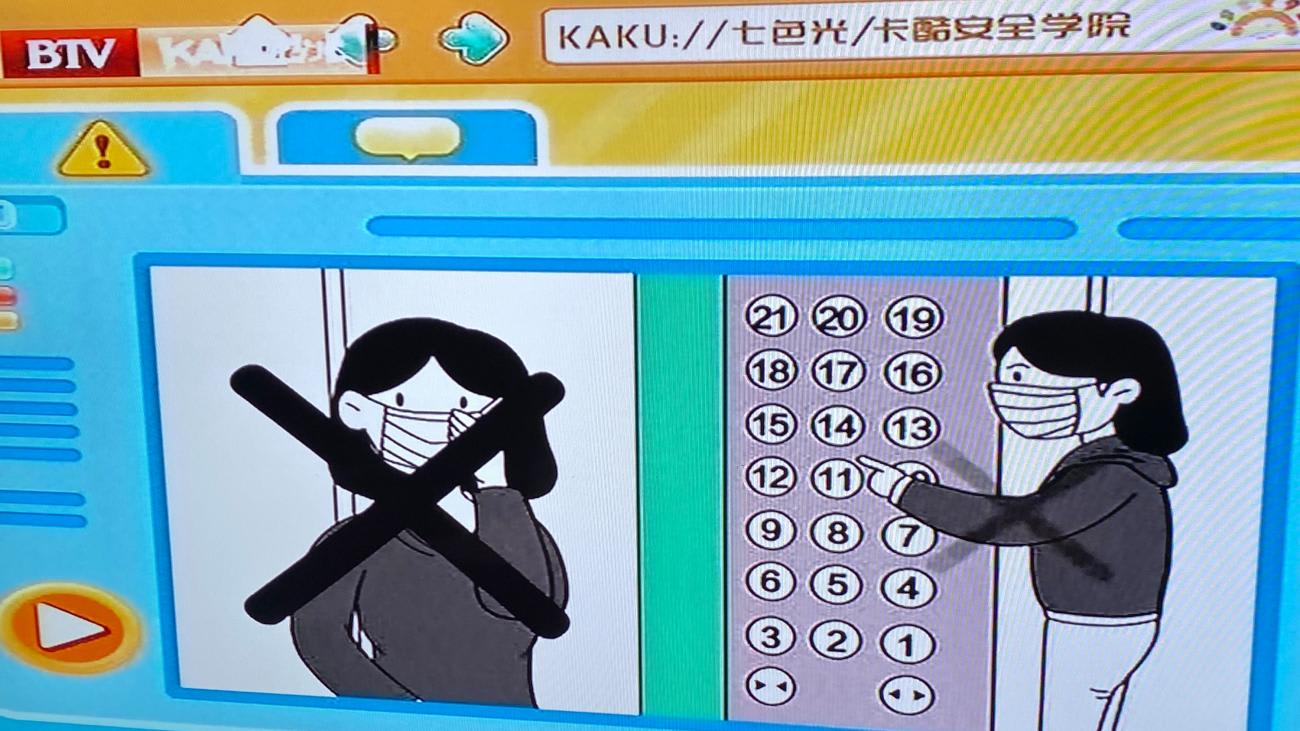

Children's television has become awash with social distancing messages, with every commercial break telling kids in age-appropriate terms about the importance of wearing masks or washing hands or not touching common areas. One of our children pointedly said, "I hate these new commercials."

These changes to society, both large and small, are looking like the new norm—one that will continue as China gets back to work. Most factory workers eat subsidized meals in company canteens. As these factories restart, seating areas are being set so that employees sit at least two meters apart, with no single employee directly facing another. Office buildings have mapped out entry and exit points to individual floors that minimize employee groupings or close interaction in hallways or elevators. Stores send WeChat message saying "we are open…. but be sure to share your green QR code" to get in. Citizens instinctively extend their arms at every building entrance, expecting the inevitable temperature check.

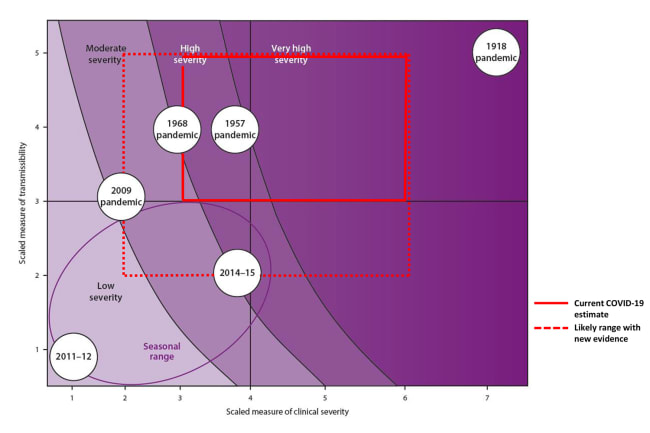

From the beginning of the Wuhan "lockdown" on January 23, we carefully observed the progress China has made in suppressing the transmission of COVID-19, with reported new infections dropping to roughly fifty per day—as well as the number of new deaths from the virus decreasing, as shown in the chart below.

New Deaths from COVID-19 in China

Number of coronavirus deaths reported daily through late March during the outbreak's peak in China

No matter your view on the origins of or the responsibility for the COVID-19 pandemic, this drop in new cases merits study—and can provide ideas for other governments and their agencies on how to deal with their specific situations.

China's experience highlights a few challenges common to all countries impacted by the pandemic.

- How to keep crowds off the street?

- How to shift idle labor from crippled businesses to those facing a sudden demand?

- How to support people's daily lives while limiting human-to-human interactions?

- How to locate and dispatch scarce medical supplies to where they're needed most?

Timeline of Events in China Over the Last Three Months

The table shows significant events in the COVID-19 outbreak and how the country responded

In summary, the actions in China can be categorized as four main efforts.

- For all people, social distancing became the norm. Authorities enforced social distancing by restricting movement and entry at the national, regional, citywide, and block level, enlisting large hordes of volunteer forces to support these restrictions. Business action, large and small—from facilitating home delivery and moving industrial capacity to reduce shortages—also made social distancing easier.

- The government increased the capacity of the medical industry to respond to the crisis and focused that capacity on the highest impact areas. They rapidly expanded production of key medical items—especially test kits and masks—and ramped up health care capacity at the outbreak's epicenter. The Chinese mobilized its national health care industry to provide needed help in heavily impacted Hubei. They also sought to reduce high-risk, human-to-human interactions by employing autonomous vehicles, robots, and other means.

- Data sharing between government agencies and the public was established and enhanced to enable more informed citizen and business decisions. Key outputs included city maps showing the location of new confirmed infections (with each district collecting details daily from local hospitals) and travel checkers that enabled one to see if they traveled in the same train or plane with someone who tested positive.

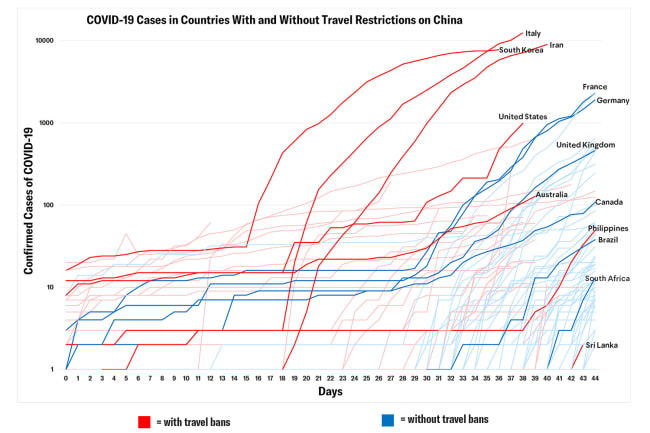

- Finally, shift effort to reduce the risk of imported cases as the disease epicenter shifted included travel bans, special quarantine hotels for landed travelers, and most recently a focus on finding asymptomatic virus carriers.

Many of these actions reflect the unique structure of the Chinese government, and therefore would not translate "directly" into an appropriate response in other countries. Many actions were tied to the unique time of year in China, the lunar new year, which is the largest human migration on the planet. As evidenced by the more successful virus suppression efforts in Korea, Japan and Singapore, multiple models exist. We must all remain optimistic that innovation – in technology, in medicine, in public-private collaboration – will let life return to normal without loss of freedom or privacy.

Making social distancing the norm across the country

In the last three months, China has used an entire quiver of levers, carrots, and sticks to enforce social distancing and other behavioral changes required to slow transmission. These levers were implemented across all areas where humans could interact, from the home to the street to public transportation and recently to offices and factories as they re-opened.

China has used an entire quiver of levers, carrots, and sticks to enforce social distancing and other behavioral changes required to slow transmission

For instance, most Chinese live in residential compounds managed by resident management committees. Nationwide, these committees became low-level enforcers of social distancing. Based on top-down mandates, they took the lead in enforcing the norms of wearing masks, sanitizing hands, and following stringent rules about entry and exit. For the most part, complexes have shut all entry points except the main gate, and each gate was manned by security guards checking temperature, allowing only residents inside, and in the early days of the outbreak, distributing masks and medical supplies. Contributors still remember waiting in line at the registration desk to reserve their first allotment of "5 masks for ten days" during early shortages. There are local variations as local authorities (such as the Beijing Mayoral Office) control local travel rules—but always with consent and potential override from central authorities.

Industries worked hard to make social distancing easier and more convenient for people, especially regarding online food and product delivery. As more than 95 percent of restaurants have remained closed throughout the outbreak, people needed new ways to get food on the table. This growth required more than a million new part-time employees in the online delivery businesses. The country launched a "shared work initiative" whereby idle restaurant and hotel employees were loaned to home delivery companies on a monthly basis, with third party companies handling the contracting, payment transfer and paperwork.

Using Data to Enable More Informed Decision Making

Despite strict government regulations and social conformity measures, it is impossible to stop all human interactions that could transmit the disease. Therefore, enabling citizens to make smarter decisions about the level of risk is critical. This requires knowing who is sick or has been sick, where have they been, and with whom have they been in contact.

At its peak, Wuhan was testing roughly 20,000 people per day, or roughly 0.15 percent of its total population daily.

The most valuable type of data available are test results, and initially China faced an issue now central in newly emerging epicenters—a lack of test kits. A broad number of startups and established companies rapidly entered the market. One leading company ramped up from making zero to about 600,000 test kits per day from the end of January to the middle of March. One major electronics manufacturer can now test twenty thousand workers per day on an internally designed and manufactured test kit. By March 5, China had distributed roughly 15.5 million tests, with kits supplied by twelve licensed enterprises (there is no official data available on total tests performed). At its peak, Wuhan was testing roughly 20,000 people per day, or roughly 0.15 percent of its total population daily.

China rolled out a national system to merge positive testing results with existing registration, location and travel databases – and then to share synthesized and analyzed information with the population. The government, led by the National Health Commission, played the central role in aggregating and communicating the information.

The system collected data from multiple sources and multiple tools, including the following:

- Local hospitals used commercial, "off the shelf" programming tools (downloaded from the app store of major Internet companies) provided by tech companies to upload patient data to government authorities.

- Residential compounds required residents to fill in location and health forms, usually via scanning a QR code (a daily requirement at the beginning of the containment measures, now weekly).

- Subways setup scanning kiosks at each car's entrance, where passengers scanned a QR code which would note the station, the line and even the car in which the passenger sat

- Domestic and arriving international travelers have been required to provide contact information, destination information and health status on a paper form.

- When entering commercial and other building, everyone must scan bar codes, triggering location data collection by the mobile telecom companies.

By mid-February, there was a new "Health Code" app launched at the district level that enabled citizens to get a "risk rating." If you score "green" you can pass freely. If you score "yellow," then you are required to take a seven-day quarantine. And a "red" score requires a fourteen-day quarantine. Citizens used this data to restart their social interactions, as people knew that "green can close the distance with green."

At the height of the crisis millions of citizens would be able to open maps of their city and answer the question "Are there any new cases and where?"

How did this data get into citizen's hands (and phones)? People's Daily, the main government media outlet, took the lead in publishing hourly updates on confirmed cases and locations. Third parties, ranging from hospitals to city governments to Internet giants like Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent made the data consumer friendly. At the height of the crisis, millions of citizens would be able to open maps of their city and their district and answer the question "are there any new cases…and where were they diagnosed?" Those who had traveled would be able to find out if they shared a train or an airplane with someone who later tested positive and take appropriate actions.

Building medical capacity at the epicenter

By now, the story of the Wuhan and Hubei lockdown is well known; no entry or exit, the rapid creation of triage hospitals, quarantining of all positive tested citizens, and grouping "similar risk" cases together to maximize health worker capacity. Many have debated the effectiveness off grid-by-grid and block-by-block management of citizen's movements and activities.

The less told story is the one in which the country collectively increased the medical capacity at the epicenter to deal with a rush of cases that overwhelmed the installed capacity previously in place.

An estimated 40,000 personnel ended up transferring into Hubei for the duration, supported by more than 20,000 students

Each of China's thirty other provinces identified and assembled medical professionals, generally 200 or more by province. These personnel were airlifted into Wuhan in early February. An estimated 40,000 total personnel eventually ended up transferring into Hubei for the duration, supported by more than 20,000 student volunteers. Shelter hospitals rapidly built or placed in existing structures (e.g. stadiums) housed infected patients with lighter symptoms. These shelter hospitals in Hubei province are now closing as cases can now be managed at standard hospitals. To enable efficient allocation of medical supplies from less impacted areas to Hubei, each city in the province was adopted by a "sister province" to which it could turn for supply allocation.

Telemedicine, enabled on both official channels and ad hoc WeChat or Zoom calls, increased onsite worker capacity by letting people who were at-home or quarantined get medical attention.

Tech platforms stepped in to enable supply-demand matching of medical equipment. Of note were many volunteer groups, including employees from global and local companies, alumni associations, and foundations, who collected supplies from inside and outside China and distributed them to impacted areas.

What's Happening Now and What's Next

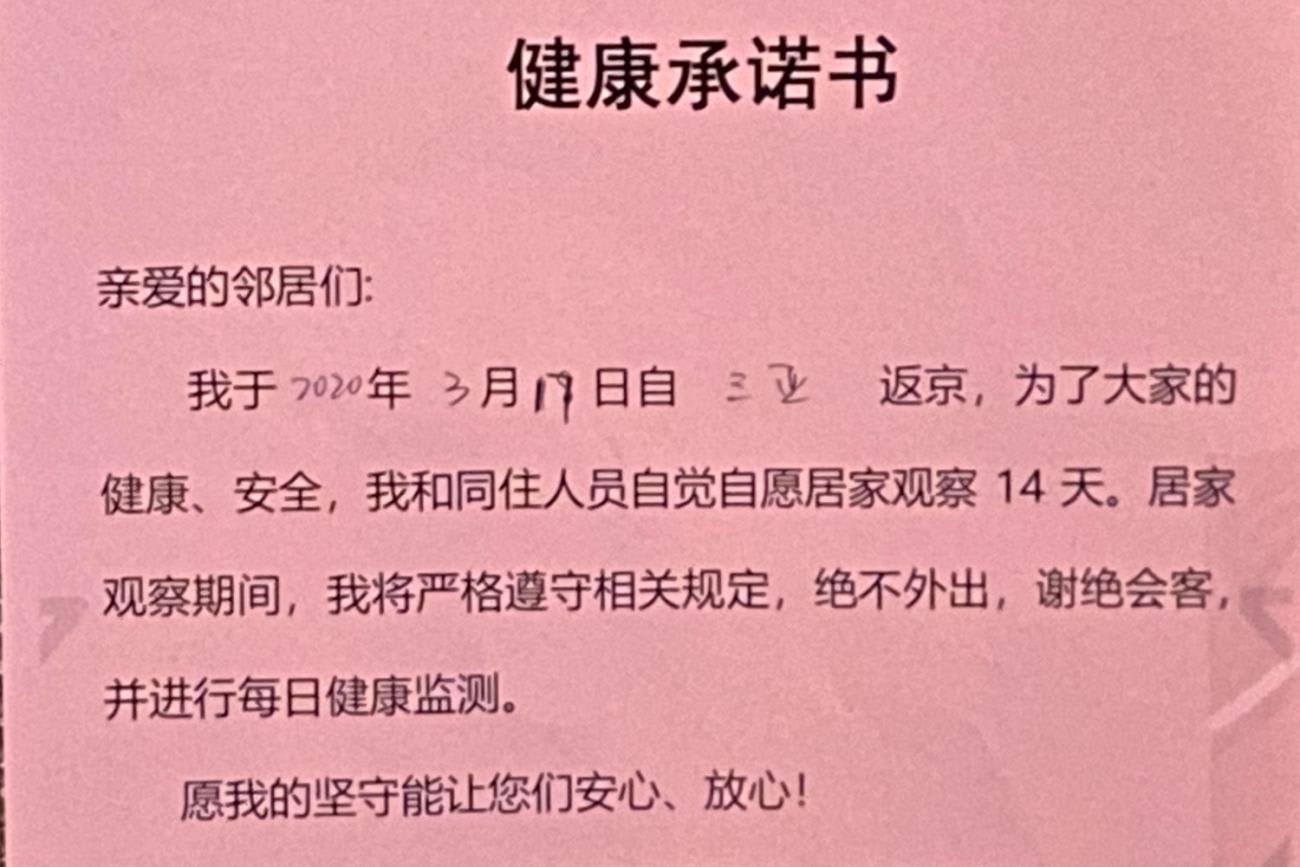

As China aims to restart its economy, strict measures are remaining in place. As factories re-open, employers are required to quarantine all returning workers for fourteen days before letting them on the shop floor. The "red-yellow-green" status of office workers is checked at the entry to commercial compounds. White collar workers sit in strategic formation at meetings, aiming to maximize social distance. Companies deliver a health report to the authorities regularly, often on a daily basis. Domestic travelers to the capital, Beijing, are required to do fourteen day home quarantine even if they have not returned from abroad.

China has begun adopting increasingly strict methods to limit re-infection and importing of cases

As the epicenter has moved to other parts of the world, China has begun adopting increasingly strict methods to limit re-infection and importing of cases. As of March 21, all arrivals to the country had to undertake nucleic acid testing (requiring six hours of waiting for the result), followed by fourteen-day quarantines at designated hotels on the outskirts of cities (self-paid, usually about $60 a night). International schools across the country are being told by the Ministry of Education, "tell your overseas employees not to come back to China yet." And, as of the writing of this article, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced the "temporary suspension of entry of foreign national holding valid visas" with no notice as to when these "closed borders" would reopen again.

Despite the recent encouraging results, there remains risk of new outbreaks. Tens of millions of migrant workers have not yet left their hometowns and returned to work. Thousands of expatriate workers are waiting to return from overseas. Most schools have not yet re-opened. More than 98 percent of citizens have not been tested for COVID-19.

Yet one sees more and more scenes of pre-virus life mixed in with the "new normal" of social distancing. Children are out in force in public squares and parks, colliding with each other as they chase soccer balls. Business lunches are back on the agenda, preferably held on balconies or open-air lounges. In Beijing, one increasingly sees people strolling without masks. People are balancing the need to "live life" versus the fear of the virus returning—a balancing act that will likely be required by all countries for quite some time.

As countries make hard decisions between economic damage, reduction in personal freedoms and public health, we remain hopeful that innovation enables the tradeoffs to be less sharp. Ingenuity, new ideas, and hard work can enable nations to make public health decisions consistent with their core values—so government can enable citizens to be both safe and free.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author thanks the Stanford University community in China, including Alan Guo, Katherine Huang, Ji Gu, Huimin Lu, Jenny Cai Maher, Chenyu Ren, Xue (Xander) Wu, Doug Cougle, Rong Zhang and Chen (Jaggie) Zhu for their contributions.