Trade rules, including those established by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and its 164 member countries, affect the movement of goods, services, and people, in addition to protecting intellectual property rights. As such, nearly all of trade policy could play a role—either positive or negative—in helping address the coronavirus pandemic. So far, for example, there is much concern that increased tariffs on imports of medicines and equipment, and export bans by countries seeking to horde their medical supplies, are exacerbating the situation.

Here's what a trade agenda designed to support the fight against coronavirus might look like:

1. Eliminate Tariffs on Imports of Pharmaceuticals and Medical Equipment

Many countries do not produce the medicines and medical supplies needed to fight the coronavirus, so they have no choice but to import the goods they need. Other countries are able to produce some or all of the requisite drugs and equipment, but not necessarily in large enough quantities or fast enough, and many of them are reliant on imports for certain active ingredients for drugs or crucial components for the production of equipment.

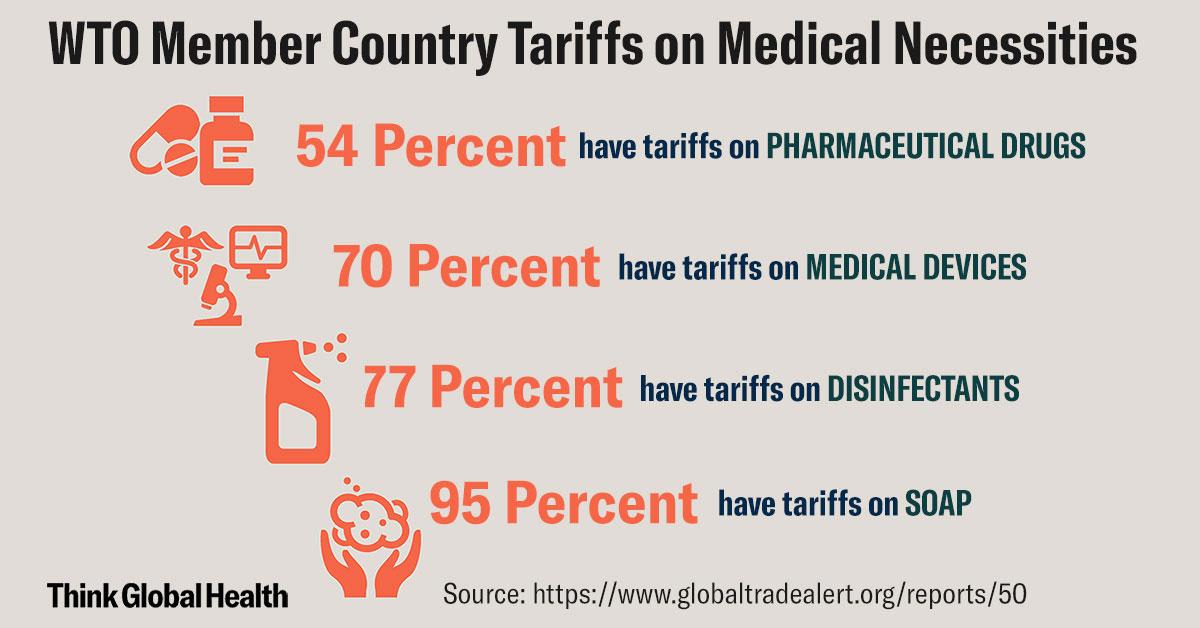

As a recent Global Trade Alert report makes clear, many countries impose tariffs on medical devices like patient monitors, ultrasound instruments, EKGs, and other diagnostic equipment (70 percent or 114 out of 164 WTO members); or on common medicines like antibiotics, painkillers, or insulin (54 percent or 88 countries); most of the world imposes tariffs on disinfectants (77 percent or 127 countries); and virtually all countries (95 percent or 155 out of 164 WTO Members) charge import tariffs on soap.

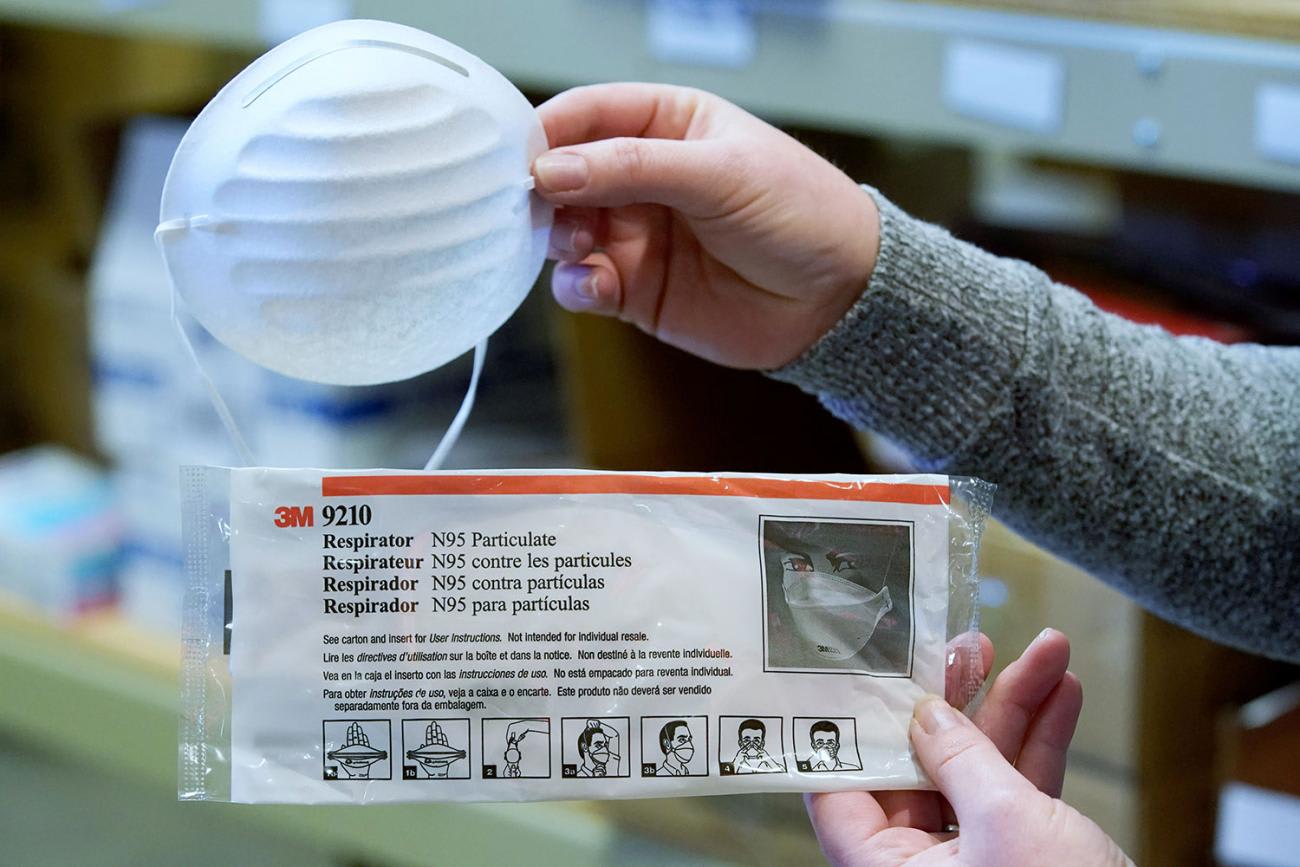

In the United States, the traditional tariffs have been exacerbated by the Donald J. Trump Administration's decision to impose additional duties—some at 25 percent and some at 7.5 percent—on nearly $370 billion in imports from China, including, as pointed out in a recent Peterson Institute of International Economics report, personal protective equipment, masks, sterile gloves, and goggles that doctors and nurses wear to limit the spread of infectious disease, along with disposable equipment such as hospital gowns, surgical drapes, as well as thermometers and breathing masks—exactly the items that risk falling into short supply as the pandemic spreads.

U.S. Tariffs have caused overall imports of medical supplies from China to decline by more than $200 million—16 percent

Also on the hook for additional duties are high-tech medical equipment—including CT scanners, ultrasound systems, patient monitors, and X-ray devices used to support the diagnosis and treatment of people suffering from coronavirus. While the Trump Administration has recently issued proclamations excluding some key items such as faces masks, medicine dispensing cups, and sterile drapes from the extra tariffs, many items remain on the list. The tariffs have caused overall imports of medical supplies from China to decline by more than $200 million (16 percent), according to the Peterson Institute's Chad Bown. While imports from other countries increased to meet some of the demand, the increased tariffs have resulted in significant additional costs on medical service providers and have left their reserve stores depleted.

Recommendation: G-7 and G-20 leaders should agree to temporarily suspend all tariffs on needed pharmaceuticals, medical devices and supplies, along with disinfectants and soap. These global leaders should encourage all other countries to follow suit. While the WTO rules include a complicated process for renegotiating higher tariffs on a permanent basis, there are no impediments to countries applying lower tariffs to imports on a temporary basis. Should countries choose, they could revert to higher tariffs once the crisis has passed, but for now, countries should apply a zero percent duty to imports of a comprehensive list of products needed to combat COVID-19.

2. Agree Not to Impose Export Bans on Medical Supplies and Medicines

Equally troubling are the actions by twenty-four countries (and counting) to place export bans on medicines and medical supplies. France, Germany, Russia, and Turkey have imposed limits on exports of medical equipment such as respiratory masks, gloves, and protective suits. South Korea has banned the export of masks and materials used to make respirators while Taiwan and Thailand have banned exports of the finished products. India, the world's main supplier of generic drugs, has restricted the export of twenty-six pharmaceutical ingredients and the medicines made from them, including paracetamol.

Such actions work to the detriment of the world's ability to distribute scarce medical resources to where they are needed most with minimal red tape

Under the WTO rules, export restrictions are generally not permitted and when imposed, must be justified under a specific set of exceptions to the general rule. While actions taken to protect the health of their people may fall within that exception—thereby technically justifying each country's restrictions on exports—such actions clearly work to the detriment of the world's ability to distribute these scarce medical resources to where they are needed most with the minimal amount of red tape. When one country imposes an export ban, others tend to follow, resulting in rising prices and pockets of scarcity outside of the silos created by the bans. Moreover, given the number of components that must cross borders in today's global supply chain manufacturing system, export bans may disrupt supply chains and delay the production of critical medical supplies or devices.

For example, the Swiss-based Hamilton Medical, one of the largest producers in the world of critically needed ventilators, was forced to delay production when needed components from Romania were blocked due to intra-EU export bans While some controls to guard against price-gouging or major purchases designed to horde materials in order to drive up prices may prove necessary, the nature of the crisis suggests starting with a policy of no export constraints until evidence of actual market manipulation is observed.

Recommendation: The G-20 countries should agree not to impose export bans or limits on relevant medical supplies and should urge other countries to follow suit. Keeping markets open is the surest way to create incentives around the world to ramp up production of needed equipment and medicines. If producers operate with the certainty that they can respond to demand both domestically and overseas, they will have a greater incentive to expand capacity and production quickly.

3. Green Light Subsidies for Production of Medicines and Medical Supplies

An additional tool that governments could use to incentivize expanded production of needed equipment and of further research into new medicines or medical devices is subsidies—typically in the form of government grants or tax breaks. Normally, trade in goods receiving such subsidies would be prohibited if the exported goods harmed competitive producers elsewhere or pushed down prices in other markets. But given the tremendous need to provide financial support to those companies capable of ramping up production of medical equipment or of speeding up research, governments should be encouraged to provide such support, and companies should be able to accept it free of concerns that their goods would be subject to challenge under the anti-subsidy rules of the WTO.

Recommendation: WTO members—either formally or informally—should reinstate the concept of a non-actionable or "green light" subsidy found in Article 8 of the WTO's Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures for all subsidies provided to companies producing medical equipment, supplies, disinfectants, and other goods used in combatting coronavirus and for all research conducted to discover vaccines against or medicine to treat the virus.

4. Waive "Buy America" Provisions Limiting Government Procurement

Many of the purchases of medical equipment and supplies to fight the coronavirus will be done by government entities—whether government-run hospitals, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or government-funded clinics. As a result, these purchases may fall under the panoply of mandates collectively known as "Buy America," which require certain government purchases to be of goods made in the United States. These buy america laws were enacted to protect U.S. businesses and labor by barring the use of federal funds to buy foreign products. However, the size and scale of the crisis and the already significant dependence on imported medicines and medical devices means that government-owned medical providers will need more—not fewer—imports, if we are to have a fighting chance against the coronavirus. These government providers need access to these materials from wherever they are most readily available, whether domestic or foreign.

The size and scale of the crisis means medical providers will need more—not fewer—imports if we are to have a fighting chance against the coronavirus

Yet it appears that the Trump Administration may be moving in the opposite direction, with White House adviser Peter Navarro announcing the preparation of an executive order that doubles down—making sure, "Every dollar of government procurement for our essential medicines and medical countermeasures is a dollar spent on 'Buy America'," he said. The administration has also threatened to withdraw the United States from participation in the WTO's Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA), which allows foreign companies from GPA member countries the opportunity to compete for certain government contracts, while giving American companies that same right in foreign markets. A withdrawal from the GPA could mean fewer foreign companies bidding to provide medical supplies to U.S. medical providers.

Recommendation: The President should use the authority granted to him by Congress to waive Buy America requirements for medical supplies, devices, equipment, disinfectants, and soap to ensure that government-owned hospitals and clinics, Veterans Affairs, and Health and Human Services have access to all needed materials to fight against coronavirus, no matter where they are made. Issuing a sweeping waiver right now would give all government medical providers the comfort of knowing that they could make necessary purchases as quickly as possible without concern over whether the items are covered by Buy America or not.

5. Speed Up the Visa and Entry Requirements to Permit Medical Personnel to Travel Where Needed

Even before the coronavirus pandemic struck, the United States was facing significant shortages of doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals.

The U.S. H-1B visa program annually lets in 65,000 workers with a BA degree and another 20,000 with a Master's or higher

The tremendous additional burden placed on front-line health care systems by the intensive treatment required for the sickest people with COVID-19 means that the United States must find ways to speed up the training and licensing of doctors and nurses and explore additional roles for nurse practitioners—but also to open our doors to foreign-trained doctors and nurses. Right now, foreign doctors or nurses wanting to practice in the United States typically are allowed entry and work permits under the H-1B visa program for skilled workers. The program annually lets in 65,000 workers holding at least a Bachelor of Arts degree, and an additional 20,000 workers with a Master's degree or higher. However, the "Buy American, Hire American" program announced in April 2018 has made it more difficult and expensive for employers to obtain H-1B visas and has resulted in higher numbers of denials or requests for more evidence.

Recommendation: The administration should announce immediate efforts to expedite the processing of H-1B visas for health care professionals, including waiving the $4,000-$4,500 fee currently being incurred by hospital and health-care providers employing foreign health care workers. The Administration should also seek a temporary waiver of the 20,000-person cap on the number of highly skilled workers who can be admitted this year.

6. Agree to Compulsory Licensing of Intellectual Property Rights on Needed Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices

Intellectual property rights, particularly patent rights, have always been a two-edged sword when it comes to medicines. The twenty-year exclusive period to make, market, and sell medicines and medical devices gives companies an incentive to incur the millions or even billions of research and development dollars that it takes to bring new products to market. But that same twenty-year period, often extended through the use of follow-on patents, can also make those medical breakthroughs extremely expensive for consumers.

That 20-year period, often extended through the use of follow-on patents, can also make those medical breakthroughs extremely expensive for consumers

When faced with the high cost of drugs to treat HIV/AIDS, the WTO amended its rules to provide increased flexibility for developing countries capable of doing so to produce anti-retroviral and other drugs under compulsory licenses, while those countries without manufacturing capability were given the right to import such lower cost, generic drugs.

Similar flexibilities may be needed to ensure that vaccines created to ward off coronavirus and medicines or medical devices designed to treat those stricken with the virus be allowed to be produced and sold throughout the world at the lowest possible cost and with the least amount of red tape or disputes over patent rights.

Recommendation: G-20 countries should commit to making newly discovered vaccines, effective medicines and patented medical devices available at reasonable costs throughout the world, whether through compulsory licenses or other alternatives to monopoly pricing under traditional intellectual property protections. All those who have the capacity to manufacture these key medicines should be given the opportunity to make them and distribute them to those in need.

The Bottom Line

Trade policy can and should do more than simply get out of the way of permitting the free flow of the goods, services, people, and medicines needed to fight the new coronavirus. Trade policy and the institutions that shape it—the WTO, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the G-20 and G-7 leaders—should seize this moment to underscore the need for collective action and supportive rules to bring about the most efficient sharing of the world's resources devoted to addressing the coronavirus pandemic.

The global scourge of coronavirus will require a global solution, and a positive trade policy could be an important part of that solution.