There are many not yet well understood aspects about the current coronavirus outbreak which was first reported in China last December and as of March 21 had infected more than 300,000 people in 170 countries. Scientists continue to assess the extent to which children are vulnerable to infection and how soon after exposure the average person becomes symptomatic. As U.S. officials sound gloomy warnings that quarantines, school closures, and limitations on social gatherings, on top of efforts to stop infected travelers from crossing the border, may not be enough to prevent widespread transmission of the virus domestically, health officials in Europe and the Middle East are facing an escalating number of cases, and hundreds of people a day have been dying in Italy this week.

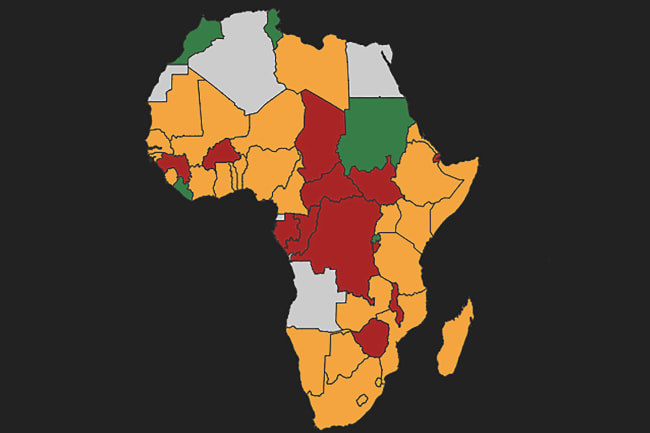

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa ranked in top 50 globally for robust health care systems sufficient to treat and protect

WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has expressed concerns that sub-Saharan Africa, where the number of confirmed cases is also starting to climb, is extremely vulnerable. Early In the outbreak, countries with strong economic and academic ties to China were identified as at risk, with South Africa, Ethiopia and Nigeria seen as especially vulnerable because of extensive trade relationships and, until recently, a large number of flights to and from China. Now countries with trade and political ties to former colonial powers France and Portugal, such as Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Mozambique, are seeing cases climb as well.

Should COVID-19, which can present with fever, respiratory symptoms, and, occasionally, gastrointestinal symptoms, begin to show sustained community transmission in sub-Saharan Africa, health care facilities in many countries in the region will be hard-pressed to receive and treat patients. The Global Health Security Index, a collaboration between the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the Economist Intelligence Unit, lists no countries in sub-Saharan Africa among the top fifty globally in terms of having "sufficient and robust health system to treat the sick and protect health workers," and just a handful within the top 100 of a list of 195.

786 million people worldwide rely on facilities without water supply and that 1.5 billion use facilities without basic sanitation, according to UNICEF

There is one aspect of the COVID-19 outbreak, and others like it, which is well understood: hand washing and the provision of sanitary facilities that enable the safe disposal of waste are critical for preventing disease transmission. The efficacy of handwashing and sanitation for preventing diarrheal disease has been long acknowledged, but more recent research regarding the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak, as well as a review of recommendations to control the spread of pandemic influenza, suggest that proper handwashing can be highly effective in interrupting the transmission of respiratory diseases as well. In 2014-2016, safe sanitation and handwashing with soap proved critical to stopping the spread of the outbreak of Ebola virus in West Africa.

While it may be difficult for many to imagine a health-care facility without basic sanitation, or water and soap for handwashing, a 2019 WHO and UNICEF report [PDF] estimates that 786 million people worldwide rely on facilities without water supply and that 1.5 billion use facilities without basic sanitation. And that is the reality for most primary care centers in sub-Saharan Africa, especially in rural areas, as well.

Indeed, the state of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) in health care facilities in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa requires urgent attention. A 2015 WHO report [PDF], which surveyed health facilities ranging from urban hospitals to rural primary care centers in 23 low- and middle-income African countries found that over a third lacked soap for handwashing and a third did not even have a source of improved water. Given that these estimates are based on self-reported data, it is likely that the actual number is even higher. Despite strong evidence to support WASH investment, a 2019 Strategic Response Plan to the resurgence of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo, highlighted irregular water supply for handwashing [PDF] as an ongoing and critical problem in managing the spread of the disease.

Facilities face incredible financial hurdles in making even the most basic infrastructure investments like washbasins and medical waste receptacles

In 2018 the WHO and UNICEF launched WASH FIT, a tool to help healthcare facilities gradually improve their infrastructure and modify behaviors related to handwashing. Limited evaluations of the implementation of the tool show that it can lead to improvements over time, but facilities still face incredible financial hurdles in making even the most basic infrastructure investments including washbasins and medical waste receptacles. This is partly explained by the fact that there has been a historic divide between the health and WASH sectors, with health practitioners sometimes asserting that it is the responsibility of the other fields, such as those focused on engineering or facilities management, to supply water and sanitation services.

At the same time, funding flows are a third [PDF] of what is needed to meet the sustainable development goals for safe drinking water, and development assistance funds for WASH projects from OECD donor governments to recipient countries was less in 2018 than in 2013.

Yet now, perhaps more than ever, investments in WASH should be seen as a key component of health security and infection prevention and control.

As global efforts to provide assistance to the most vulnerable countries scale up, it's time for the health sector to see WASH investments as an integral component of the international response – and not just in health care facilities but in also public settings like schools, markets or places of worship or government buildings where people are likely to congregate.

With recent research suggesting that the novel coronavirus can survive on such common materials as plastic and stainless steel for several hours, and with a fully tested and approved vaccine for COVID-19 still months—if not years—away, governments and organizations that support health security in sub-Saharan Africa would do well to invest resources in WASH programs now because they are proven to save lives.