A looming epidemic of COVID-19 in Africa presents a deadly threat. This is especially the case in densely populated urban areas with limited opportunities for social distancing, poor baseline systems to support hygiene and sanitation, and comparatively few level-one trauma hospitals or health care facilities that can provide respiratory support. Two COVID-19 cases have been diagnosed on the continent, and testing of other potential cases is underway.

Yet, African leaders are not starting from a scratch. African countries have been fighting increasingly successful battles against a number of pandemic infectious diseases over the last several decades, have built enormous human capacity and systems capacity for health care. Substantial improvements in health have been made over the last decade and a half, driven by well over $100 billion in investments from central governments, external donors, and health agencies led by PEPFAR and the Global Fund, but also Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative and others.

Because of the robust responses to these diseases, many African countries are starting from a very different baseline than twenty years ago

Mortality due to HIV/AIDS in eastern and southern Africa has decreased by over 50 percent from its peak in 2004 due to the rapid expansion of treatment programs, and new HIV infections in the region have decreased by 28 percent since 2010. Malaria cases in Africa have decreased by 40 percent from 2000–2015, and many countries in the region are on track to meet aggressive malaria control goals. And since the 1980s, the polio response has led to the virus' near elimination on the continent and has tangibly strengthened disease outbreak preparedness.

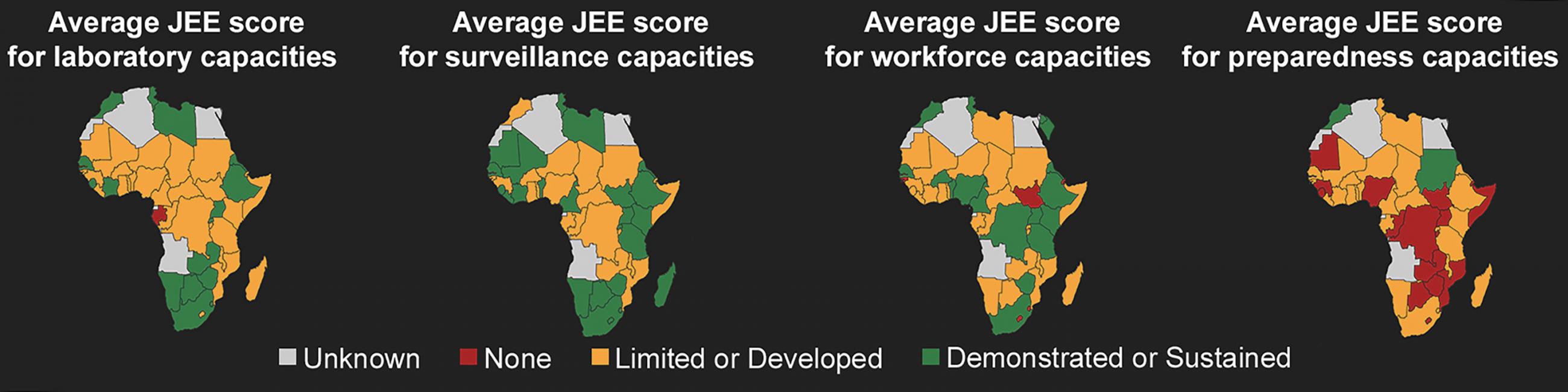

Because of the robust responses to these diseases, many African countries are starting from a very different baseline than twenty years ago. Although this has not generally included support for ICU-level care that will be required by the sickest people with COVID-19, what these investments have supported are increasingly human resource for health, supply chains, information and surveillance capacities for prevention, detection and long-term response capacity against diverse infectious threats.

Mathematical models and experience other countries suggest serious potential loss of life on the Africa continent from COVID-19

However, unlike malaria, HIV, TB, polio (and now Ebola, for which there is a vaccine), COVID-19 is a disease caused by an easily transmitted respiratory virus, SARS-CoV-2, with no current vaccine, approved treatment, or cure.

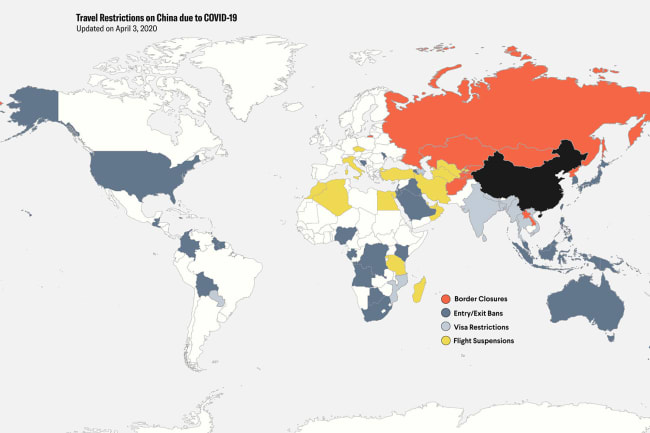

Mathematical models and experience from China and other countries with new cases suggest serious potential loss of life on the Africa continent from COVID-19.

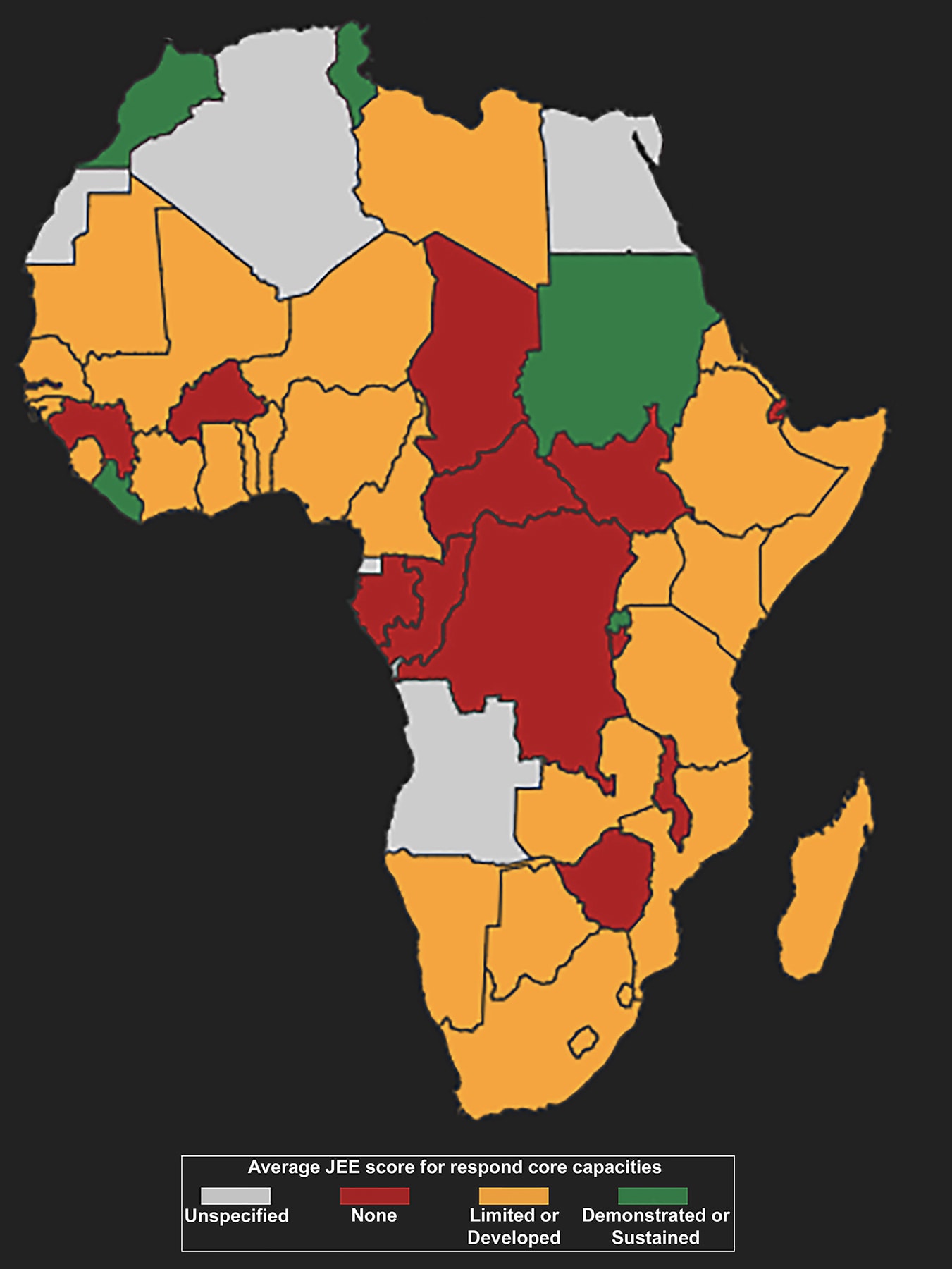

This is especially likely to be the case in those countries with weaker health systems—and in the short term, those with highest risk of importation of the virus from heavily affected provinces in China.

Although countries in the region have a relatively low overall level of preparedness—in terms of their overall ability to prevent, detect and respond to public health emergencies in a timely fashion—there is value in thinking not just from the perspective of everything that is missing in the race to preparedness, but also how to make better use of everything that is present. And with leadership and targeted investment, to deploy resources most strategically to advance preparedness. This is especially important given the low and slowly growing levels of government health expenditure in the region.

Support for Strong Regional and Global Leadership

The first step is for the international community to recognize and support African leadership in public health. African leaders we have spoken with in the past weeks have expressed great appreciation for and trust in regional leadership from the Africa Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization (WHO).

About 11,000 African health workers have been trained using WHO's free online courses on COVID-19

Africa CDC was launched just three years ago as an affiliate of the African Union. Its director, John Nkengesong was just appointed by WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, to be a special envoy on COVID-19 for Africa. Both men share a deep understanding of health systems in the region and a commitment to supporting local leadership, and both their organizations have been spearheading regular preparedness discussions with African leaders to put in place specific measures from airport screening, to expanding the number of laboratories able to test for COVID-19, to starting to cross-train health staff for national responses. And over the past month, about 11,000 African health workers have been trained using WHO's online courses on COVID-19, which are freely available at OpenWHO.org.

Yet, the Africa CDC's budget is limited, and WHO is currently hundreds of millions of dollars short of the needs outlined in its Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan, and as of today has received less than $2 million of pledged COVID-19 contributions.

Better to both fully fund the U.S. response and provide robust funding to support African and other regions with vulnerable health systems

The Donald J. Trump Administration has asked Congress for $2.5 billion in emergency funds related to the COVID-19 response. Yet the request includes only $1.25 billion in new funding (less than a fifth of what the Obama administration requested during the 2014/2015 West African Ebola epidemic), and relies on a damaging $535 million re-appropriation of Ebola funds. Moreover, the administration's budget for COVID-19 provides very little support to the international response. This is a mistake. Better to both fully fund the U.S. response and provide robust funding to support African and other regions with vulnerable health systems, as proposed in Senator Schumer's request.

Building from Strengths Within Existing Disease Responses

There is of course still much more to be done in terms of more fully "converging" single disease fights such as the HIV/AIDS response with closely related efforts such as pandemic preparedness, health security, and primary care. We recently argued that even as the HIV/AIDS response become more focused due to resources that have not grown in over a decade, there are opportunities to build from the systems developed for the HIV response to support broader health responses.

As one of the authors (CBH) did in Zambia in 2014 and 2015 in preparation for the possible spread of Ebola, it will be essential for consideration of how the health system elements largely built to support single disease responses, can support the COVID-19 response—from adding in personal protective equipment and other supportive medical supplies to the supply chain, to building capacity for rapid laboratory testing, to prepping front-line clinics and hospitals.

Strong surveillance built during the polio response helped limit Ebola to 19 cases in Lagos in 2015—a city of 21 million

This includes planning for surging capacity as waves of people fall ill and are brought to medical centers, training on approaches for rapid triaging to keep people who are sick from spending hours in crowded waiting rooms and spreading the virus to others, and establishing communications networks and temporary facilities for quarantining people who test positive for COVID-19. Leveraging other disease responses and extensive preparation turned out to be essential [PDF] when the first Ebola case entered into Nigeria in 2014. The index case was first recognized by an astute physician, and individuals trained through CDC's Field Epidemiology Training Program were quick to contribute to contact tracing efforts. The PEPFAR-supported laboratory at Lagos Teaching Hospital diagnosed most of the cases. And strong surveillance capacities built through the polio response played a key role in limiting the outbreak to an astonishingly low nineteen cases in a city of 21 million.

While much of the discussions about capacity focuses on hospital-based care, some of the most important contributions to containing COVID-19 will take place deep in the community. Countries that have invested in strong community health delivery programs, such as Ethiopia, Ghana, Rwanda and Malawi, will benefit from being able to activate this network of hundreds of thousands of trained, trusted community health workers that will be able to carry much of the burden—and do it deep within communities. They will help to guide the response by being on the front-lines if schools and churches need to be shut-down and if home quarantines are necessary. They will also be the voices of reason to counter misinformation, quell panic, or address vocal concerns of people in their communities.

Building Coalitions Early for Coordinating Non-Governmental Support

Government leadership at national and local levels is absolutely key to any success in preparedness and response. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), however, may play a particularly key role in fighting COVID-19 in African countries. Given current funding patterns, much of the funding from PEPFAR, Global Fund and other global health efforts flow through local and international NGOs, which means they will play an oversized role in the implementation of prevention, detection, and response to emerging infectious epidemics than they would in other settings.

Success in Africa's battle against COVID-19 will come from leadership, planning, and cooperation across governments and non-governmental groups

As individual organizations, NGOs may be constrained in their flexibility, since each of them has scope limited to the specific activities they are funded to pursue—and responsibilities to their donors to do so. Yet together, they bring substantial capacity, of which at least some proportion can be deployed in ways that serve both their grant-funded work and response to urgent needs such as the response to COVID-19. But the effectiveness of that response can only be realized if all the NGOs are working together in a highly coordinated way with the countries' government agencies and local authorities. Donors can facilitate this by pro-actively allowing for local flexibility that ensures for prioritization of urgent activities, while also being strategic to mitigate harms to other ongoing health programs. Updating mapping of infrastructure and multi-sectoral resources is critical to the IHRs, as is the coordination mechanisms among NGOs, which require early attention and resources.

Success in Africa's battle against COVID-19 will come from leadership, planning, and cooperation across governments and non-governmental groups to make the most of each society's health system assets. In addition to meeting direct medical and public health needs, donors should pay particular attention to investments in potentially overlooked opportunities to promote stronger coordination and communications that would help make better use of existing capacities.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story was corrected to reflect the fact that the first Ebola case entered Nigeria in 2014, not 2015 as originally posted—and to add that the index case was first recognized by an astute physician.