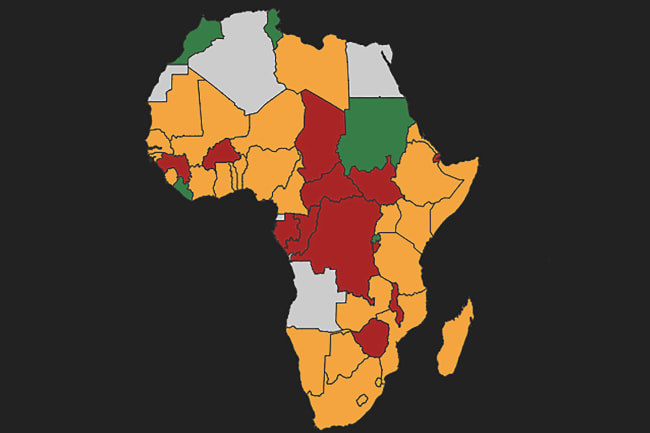

If there's one universal with COVID-19, it's that at this point in the pandemic, preventing and ultimately controlling local outbreaks relies largely on human behaviors. We have no effective vaccines, so the actions or inactions people and their communities take to modify behavior and mitigate spread are our only means of control—a crucial common denominator that has had a significant impact on outbreak outcomes as far afield as from Wuhan to Milan and from Lagos to Los Angeles.

But the universality ends there. If the need to socially distant is the same everywhere, the best way to implement those practices is not. To get people to make common-sense decisions, follow the advice of experts and leaders, and embrace fundamental daily changes in their behaviors and routines, they must be effectively engaged on a community level.

Public health measures are only as effective as the proportion of the population that adheres to them

A recent geo poll in sub-Saharan Africa indicates a high level of awareness of COVID-19—94 percent of 1,350 respondent, in three countries: Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa were aware of what the term means. However, this knowledge is not fully translated into behavioral changes. For instance, reports of violence following closure of mosques have been noted in the state Kastina, in northwest Nigeria. However, due to growing opposition, these venues for worship have reopened for Friday congregational prayers in the state and other parts of the country. Given the exponential rise in the number of cases in northwest Nigeria and virulence of the pandemic, public health measures are only as effective as the proportion of the population that adheres to them.

Interestingly, some of the control measures imposed across the continent were modeled on those of developed countries. While these are evidence based, they are not context-specific, and therefore they may be not locally adaptable in Nigeria and other parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Because every different area will have its own multifaceted, culturally-specific context informing community perception, every local outbreak is somewhat exclusive. A one-size-fits-all response is not applicable in Nigeria or most anywhere else in sub-Saharan Africa. Responses must be adjusted to local realities, including culture, beliefs and socioeconomic conditions.

A one-size-fits-all response is not applicable in Nigeria or most anywhere else in sub-Saharan Africa

Among the average northerner in Nigeria, COVID-19 is purported as a hoax—misinformation deployed by the media and the government to further deprive the region, particularly as many of the earlier confirmed cases were among the political class. While the privilege of access to test facilities and international mobility among the upper classes of society exist, the lingering Boko Haram crisis and widespread misappropriation of funds for victims of insurgency in the northeast region further compound the issue. Thus, for many in this region, COVID-19 may appear to be a fabrication and yet another deceitful scheme for its leaders to access federal allocated resources.

Realities in Nigeria's Kano State

Meanwhile, reports of spikes in incidence of mysterious deaths have been noted in Kano State in northwest Nigeria. Although state authorities had initially claimed it was unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic, prelimary findings from the nation's COVID-19 task force reveals potential links with the outbreak.

Despite these realities and a surge in number of cases, many residents still do not believe the virus even exists

The state capital Kano is the second largest city in Nigeria, and the dramatic increase in number of confirm cases has been a source of concern for the Nigerian government. A major risk factor facilitating the spread in Kano State and other parts of northern Nigeria is the almajirai children, who are receiving an Islamic education. The almajiranci system has been a longstanding institution in northern Nigeria where children between the ages of three and twelve are placed in informal boarding schools to learn the Koran under guidance of tutors, called mallams. However, for decades, this system has been abused and neglected. Many of these children are homeless and are confined to begging for alms in the streets in order to survive. The exact number of almajirai in Kano state is not known, but it is believed to be approximately 300,000. Intended plans to send students back to their various states of origin pose a potential risk of introducing the virus to newer population—a burden the country can ill afford at the moment.

Despite these realities and a surge in number of cases, many residents still do not believe the virus even exists. This has been a major source of challenge in mitigating the epidemic. Thus, in order to understand and address this gap in high-risk behaviors that reinforce resistance to public health measures across the country, community engagement is vital.

Issue Framing: Rally Around the Flag—or Throw the Flag in Someone's Face

Central to how an issue is understood or perceived publicly is its framing. How an issue is framed is of paramount importance, and no form of issue framing is one size fits all—as people see or interpret the world differently.

In the United Kingdom today, the SARS-CoV-2 virus—which causes COVID-19—is perceived as a threat to the National Health Service (NHS). In response, a clear message is being relayed to the public to "PROTECT THE NHS." This seventy-year old health institution is a symbol of pride and unity among the British people. Invoking it has instilled a sense of ownership in the response, raising the public awareness that each person's actions or inactions are critical and they are not merely playing a passive role.

No form of issue framing is one size fits all

In the United States, on the other hand, the rhetoric has been more divisive than unifying—both internally, between the two major political parties, as well as well as outward-facing statements directed at China and lately the World Health Organization (WHO). Framing the pandemic as deception by Beijing or WHO complicity may have sown further seeds of disunity among people who were already divided. Several in-your-face protests have erupted from different groups, largely out of resistance to lockdown or stay at home directives. The confusion comes amid rising mortality figures, with many states relaxing lockdown directives despite a lack of viral control.

Nigeria has the opportunity to use a unifying form of issue framing as well—by evoking its own earlier successful response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak, which was described as a "piece of world class epidemiological detective work." As a result of the heroism of a Nigerian medical doctor who physically restrained patient zero from leaving the health facility—despite pressure from the Liberian embassy—and later died as a result. This tragedy helped in revitalising a sense of nationalism and patriotism among Nigerians, a catalyst for behavioral change during that event—and one that serves well in the coronavirus pandemic.

New Strategies for Controlling COVID-19

In order to control the spread of the coronavirus across Africa, efforts should go beyond traditional public health measures. Response coordination should also be framed around symbols or figures that strengthen national unity in order to sustain community mobilization. Hence, it is crucial African heads of state engage communities in ways that echo their shared beliefs and ideologies, and that approach should be reflected in planned behavioral change strategies.

Nigeria is a non-secular state, with an equal proportion of both Christians and Muslims, 49 percent respectively. As Ramadan begins, convincing faithful Muslims to stay at home is an uphill task. Thus, unequivocal messages from religious leaders are crucial.

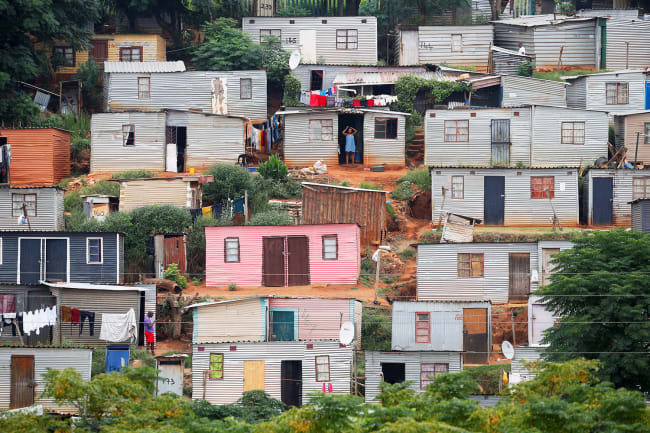

About 87 million Nigerians live below the poverty line—on less than $1.90 per day

We need to be mindful that about 87 million Nigerians live below the poverty line—on less than $1.90 per day. For many in this category, they rely on daily income for sustenance and survival. Although the government created a social safety net in the form of conditional cash transfers to cushion the financial fallout for the poorest of the poor, it is imperative that not only the remote disbursement of such funds be marked with equity, transparency, and accountability—but that the people also perceive it to be so. People are far more likely to support a system that unswervingly protects the lives and welfare of their families and communities. These palliatives will not only go a long way in protecting vulnerable citizens but in addition, may also potentially help in strengthening trust and regaining confidence the system.

While there are clearly no easy answers to these issues, any measures adapted would not be free from difficulties. Community engagement guarantees two-way communication, and it would give a sense of responsibility during this period. Feedback received from communities on their current perceptions and what rumors are circulating would potentially increase the effectiveness of social mobilization strategies. Nigerians should have a sense of ownership and participation, that they are playing a part in mitigating the outbreak of this deadly pandemic.