Foreign doctors spreading Ebola in Congo have been killed by locals near Lake Kivu. This was the bogus headline posted on my North Kivu Life Facebook group over Thanksgiving weekend last year. Dozens of comments followed that were as offensive as they were untrue: Duh, they are obviously sick of the UN murdering their children…The population of Congo is probably westerner's favorite guinea pig for their drug experiments…Good, these quacks are getting what they deserve. As a foreign doctor formerly working in Eastern Congo, I was deeply disturbed by these malicious and baseless remarks. But I was hardly surprised.

At the time, only sporadic cases of Ebola were reported by the Ministry, but even then social media was being bombarded by medical hoaxes and hearsay

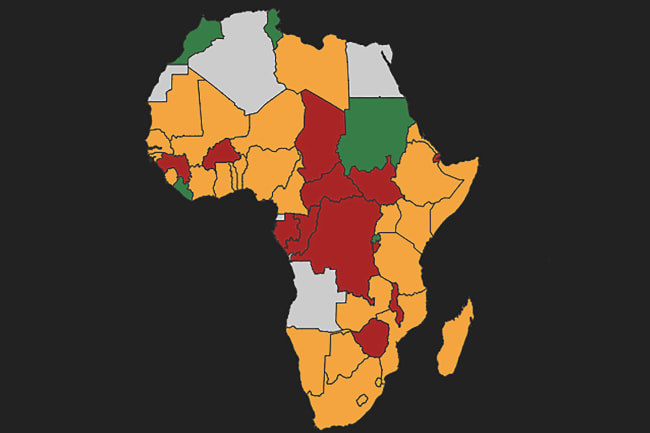

Since the beginning of the tenth and most recent outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo, conspiracy theories about the epidemic have thrived online. Some claim the virus was manufactured in government labs by former President Joseph Kabila Kabange in order to drive down voter turnout during the past election. Others argue the disease doesn't even exist—it is just a story invented by the private mining corporations as a means of controlling the country's flow of natural resources. These rumors permeate the overcrowded urban enclaves and surrounding migrant communities in Eastern Congo where in 2017 I joined a research team monitoring the health status of refugees and internally displaced persons in North Kivu Province. At the time, only sporadic cases of Ebola were reported by the Ministry of Health, but even then social media was being bombarded by medical hoaxes and hearsay.

In a corner of the world where experts say only a quarter of the population has internet access, it is easy to underestimate or altogether dismiss the deep impact of social media on public health. Accessing Facebook and WhatsApp can be easier than finding clean drinking water in Eastern Congo. Mobiles and SIM cards are shared, and credits or minutes can be traded in lieu of hard currency.

Accessing Facebook and WhatsApp can be easier than finding clean drinking water in Eastern Congo

The majority of displaced communities in the area will maintain at least one if not several charging stations—often a single-room hut with a solar panel affixed to the roof. Even if only a wealthy minority have access to a smartphone, it takes just one person logging onto his or her platform of choice to find images of doctors wearing bright yellow personal protective gowns carrying dead bodies within quarantined zones—pictures taken during the 2014 Ebola pandemic in Western Africa. These photos are recirculated and augmented on social media as proof that the highly effective Ebola vaccine being administered at designated treatment centers is actually a campaign to purposely infect Congolese women and children with the disease.

From here, news passes from person to person, between parishioners attending Sunday church services and patrons at the roadside bars drinking bottles of Primus beer. Migrant workers who transport water in the cities travel home to outlying villages during the rainy season, warning family and friends to stay away from regional clinics offering so-called immunizations against Ebola. And in a series of attacks targeting health facilities, men with guns have accused health workers of being spies sent to wipe out the Congolese population as they shoot indiscriminately at clinicians treating patients. This is how bad information about Ebola goes viral. The consequences are almost as horrific as the virus itself.

This is not to condemn Facebook and WhatsApp as the root cause of mistrust and violence in Eastern Congo. For the last three decades, the region has been crippled by socioeconomic instability and endemic conflict without which the distribution of medical misinformation and disinformation would be far less devastating. However, social media has become a powerful vector outpacing our capacity for clinical innovation. This presents alarming implications not only for the current Ebola crisis, which within the last two months is showing welcome signs of reprieve, but for emerging public health emergencies around the world.

Social media has become a powerful vector outpacing our capacity for clinical innovation

The evolving COVID-19 pandemic offers another, more salient example. Conspiracies have emerged on Facebook blaming China for engineering and purposely introducing the virus into the population, and accusations have been hurled back and forth criticizing both China and the United States of engaging in biowarfare. As the global spread of new cases continues, a number of countries have responded by declaring ad-hoc legislation subjecting its citizens to severe penalties including heavy fines and jail time for posting false content about COVID-19 on social media, even when they are doing so based on genuine misconceptions rather than an intent to deceive. The majority of nations remain ill-prepared and have no mitigation tactics in place. The recommendation from the United States Department of Health and Human Services is to simply trust in the experts, not Facebook.

This lack of strategic consideration is insufficient and dangerous. A siege of online distortions is impeding our ability to respond to the multiple outbreaks we are currently facing, and a vaccine or cure will have little effect if people are too afraid and confused to seek out proper care.

What is urgently needed is a giant leap—a comprehensive code of ethics for platforms and users respecting and protecting public health on social media

Regulation of medical information on social media is now paramount. The burden of this mandate cannot fall on governments alone; purely legislative approaches may do more harm than good if enacted by state agencies lacking the capacity or integrity to enforce them. Primary responsibility falls on all relevant platforms to stop the infodemic plaguing our health system. Many social media companies are already implementing corrective measures to address the issue. Facebook has committed to taking down fraudulent posts on its site related to COVID-19. It has also piloted educational pop-up windows that appear in search results for coronavirus to increase access to evidence-based data. And earlier this month, the company hosted the World Health Organization at its headquarters in Menlo Park where multiple industry leaders from the tech sector engaged in discussions and exchanged ideas on how to counter inaccuracies about COVID-19 on their sites.

While these are small steps in the right direction, what is urgently needed is a giant leap—a comprehensive code of ethics respecting and protecting public health on social media to which all platforms and their users are beholden. Social media companies must develop and integrate robust, transparent safeguards against medical misinformation and disinformation on their sites grounded in the same general principles that defend our basic human rights, including our right to health. This requires a collaborative approach with government institutions as well as non-governmental organizations to ensure fair and consistent enforcement.

We have reached a critical juncture where free speech and free markets are colliding with public health and safety at a perilous rate on social media, and we need rules of the road to prevent us from crashing into further health hazards. Because with accelerating urbanization, human migration, and climate change, the variation and frequency of infectious diseases are likely to rise.

What we are seeing with Ebola and COVID-19 are warning signs of a rapidly approaching future. With the right policies in place, social media can be a powerful weapon in combatting epidemics in the post-truth era. Or it can be a catalyst for the next global health disaster.