A new study, published in The Lancet, charts how the 25 leading contributors to global diseases have shifted between 2010 and 2023.

Some leading causes of premature death and years of healthy life lost to disability or illness have plummeted—especially risks related to child and maternal health and unsanitary environments. Other challenges, mostly those connected to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, have surged. The findings speak to the power of development assistance and public health interventions to improve lives across regions—as well as to the significant impediments rising anew.

"NCDs are by far the biggest thing that kills human beings on this planet, and they're getting worse," says lead author Simon Hay, director of research strategy at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), an independent population health research organization based at the University of Washington. "There's a massive opportunity to intervene and save healthy life by taking simple actions," Hay says.

The findings—which brought together 3,291 collaborators from 112 countries—are the seventh iteration of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study, an effort launched in 1990 to measure and compare health outcomes across the world. This edition presents the most comprehensive audit of the state of global health following the COVID-19 pandemic, says Hay, who is also a professor of health metrics.

NCDs are by far the biggest thing that kills human beings on this planet, and they're getting worse

Simon Hay, director of research strategy at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

Hay and his colleagues examined the burden of 375 diseases and injuries and 88 risk factors affecting healthy life expectancy—from particulate matter pollution to high blood pressure. Their data came from 204 countries and territories and more than 310,000 sources, from disease registries and surveys to peer-reviewed scientific literature. They used a variety of statistical procedures and modeling approaches to fill in gaps and standardize the data so that it could be compared and combined.

An analysis of the age-standardized percentage change in the 25 leading risks to health between 2010 and 2023 revealed several notable trends. The risks that experienced the greatest declines over that time included unsafe water, sanitation, and child growth failure—a consequence of undernutrition and poor early-life health that leads to physical deficits.

"That's a continuation of a trend that we've seen over 20 or 30 years," says Michael Brauer, a principal research scientist at IHME and an environmental health scientist at the University of British Columbia. "It doesn't mean we should let our foot off the gas, but it's a clear success."

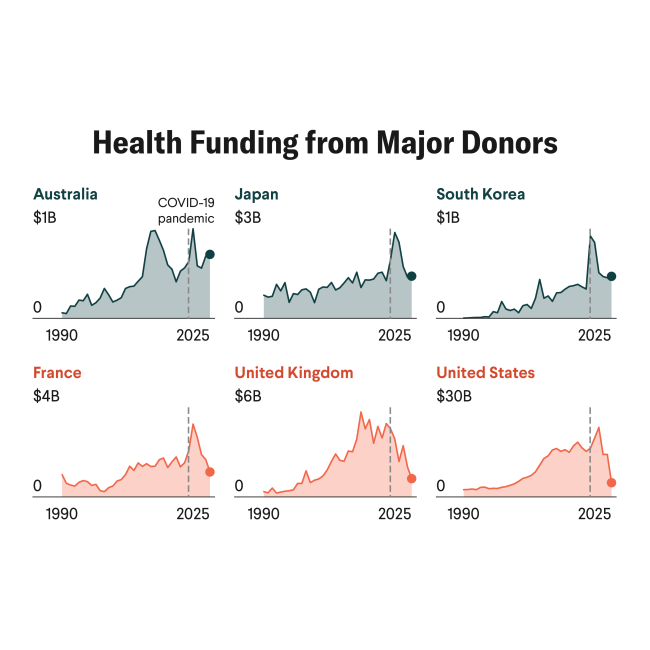

The lessening of these and other development-related health risks, in turn, helped to drive an "absolutely staggering" drop in certain infectious diseases, Hay says. This pattern included a nearly 50% decline for diarrheal diseases, 43% for HIV/AIDS, and 42% for tuberculosis. "We should be massively proud of that as an international community," Hay says, adding, however, that such public health successes are now threatened by the closure of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the withdrawal of other key sources of foreign aid. "I doubt very much we will have such a nice thing to report in GBD 2025," he remarks.

The most concerning finding was the steep rise in certain metabolic-related NCDs, including high body mass index (BMI) and high fasting blood plasma glucose—an indicator of prediabetes or diabetes. As countries around the world become richer, problems "that largely have to do with diet and physical activity" are gaining more traction, Brauer says.

The findings indicate that the rising burden of NCDs "needs urgent attention," says Vedavati Patwardhan, a research scientist in gender equity and health at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the work.

"The GBD is one of the few data sources on the diverse risks and causes of morbidity and mortality globally, regionally and over time, making the results from the latest round an important guideline for global health priorities," she says. "We need policies that promote healthy diets, active living, and mental health, and that provide social protection to reduce vulnerability."

Prabhat Jha, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, casts doubt, however, on the real-world applicability of findings that relied so heavily "on complex econometric models that in turn rely on sparse input data." Because of this limitation, Jha says the new study's estimates of global risk factors and trends are "not reliable" and "largely uninterpretable."

In general, he adds, "the GBD estimates correlate poorly with actual country level mortality by cause and show inexplicable variation in risk factor contribution to mortality." He says, for example, low fruit intake was associated with 2.4 million deaths in GBD 2017 but only 1 million in GBD 2019—and that the GBD 2015 study showed cholera was the leading cause of diarrheal deaths in Canada.

Brauer says that he and his colleagues have a vested interest in constantly updating their models to include the best available data, but among the challenges is that in some countries those data often are not collected, are missing, or are of variable quality. "The response to that isn't to throw up your hands and say, 'This is garbage,'" Brauer says, but rather to do the best work possible with what is available and to encourage countries collect more robust data.

Adnan Hyder, dean of the Boston University School of Public Health, who was not involved in the work, thinks the new study includes sufficient explanations of the methodological approach and limitations. "It's an outstanding piece of work," he adds.

Although the findings on significant reductions in childhood morbidity and mortality are "fantastic," Hyder continues, the absolute increase in NCDs is a major concern for the future. Already, he adds, there are signs that some countries are not taking this threat seriously enough. In September, for example, the world missed a chance to prioritize NCDs when a high-level UN resolution on the topic failed after U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. vetoed it. "I was personally very disappointed," Hyder says of the declaration's failure to pass.

The draft resolution proposed global targets for addressing certain NCDs by 2030 and had the support of a coalition of more than 130 countries, including China. The measure will now be subject to a formal member state vote.

"I hope the world will come together to invest in NCD treatment and prevention," Hyder says. "It's very clear that if we don't do this, it's going to cause a very high burden for our populations."