Nearly six months after the Donald Trump administration announced sweeping cuts to development assistance for health (DAH), researchers are beginning to understand how the drastic drop in funding is reshaping global health governance and programming.

"The climate has fundamentally changed," says Joseph Dieleman, who leads the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)'s health resource tracking team. In a new report, the team found that DAH declined 21% between 2024 and 2025, driven largely by a 67% drop—more than $9 billion—in U.S. financing.

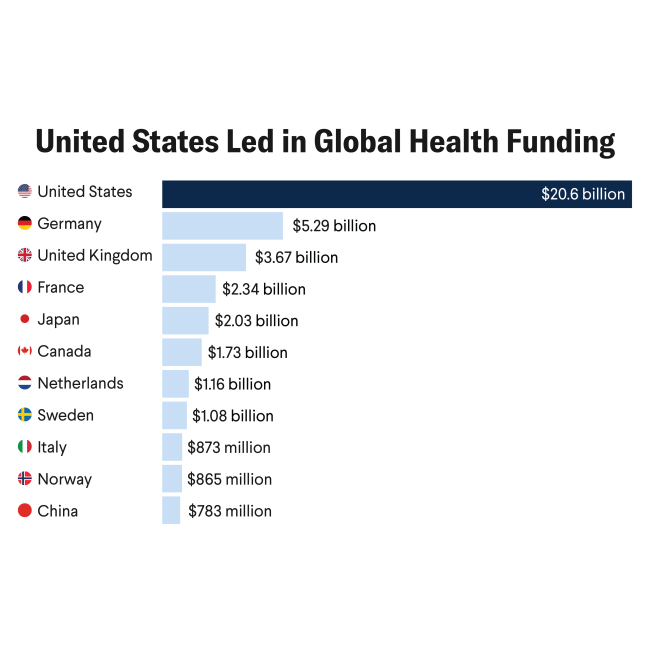

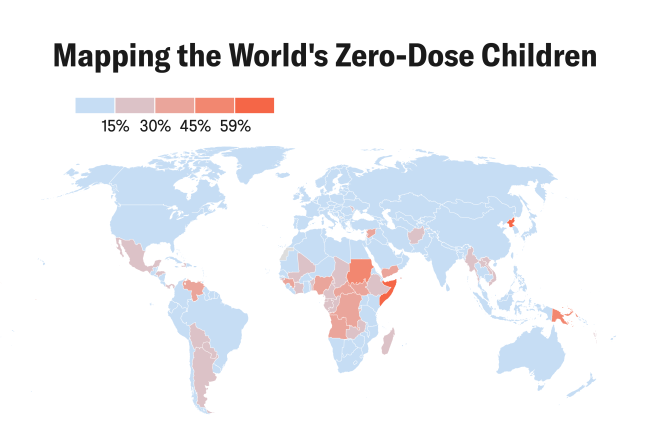

The United States has historically been the largest funder overall, contributing around 35% of DAH each year for the past decade. The shift has been felt most acutely in low-income countries where disease burdens are high, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa. "The countries most dependent on development assistance and are also the least capable of filling the gap," said Dieleman.

According to their analysis, Gambia, Lesotho, Malawi, and Mozambique have been hit the hardest relative to their small budgets, with reductions in total health spending up to 16.5%. Nigeria lost the most development assistance in absolute terms, more than $400 million.

"It's a small part of the U.S. budget, and it has real repercussions for Americans as well as people on the other side of the world," said Dieleman.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the 25% reduction in funds is already hindering efforts to control the spread of major infectious diseases such as HIV and malaria. The United States financially supported much of the world's HIV response, including through the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). In late July, PEPFAR's budget survived a rescission vote in Congress, but the New York Times, citing leaked documents, reports that the State Department has discussed phasing out the assistance program. Global immunization programs also face budgetary shortfalls, the United States having withdrawn its support from vaccine provider Gavi.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and foundations that relied on U.S. grants saw a 23% loss in funding overall, leading to downsizing at health and advocacy organizations that include FHI 360, RTI International, Population Services International, and the International Rescue Committee.

UN agencies have also laid off staff and downsized operations due to cuts. The UN World Food Program, the largest international organization dedicated to hunger relief, told staff it would cut about 6,000 positions after facing a 40% reduction in funding this year. The news comes as starvation and acute malnutrition deepens in conflict zones such as Gaza and Sudan. UNAIDS announced a large restructuring plan to scale back operations and reduce its staff by 54% and has reportedly discussed plans to close its secretariat by 2030.

The United States has driven the bulk of cuts, but is not alone. Despite their relatively lower contributions, Finland has cut its DAH by 11% ($14.9 million), France by 33% ($555.1 million), Germany by 12% ($304.5 million), and the United Kingdom by 39% ($796.1 million). Yet the U.S. cuts were "the most abrupt and most substantial in order of magnitude," says Angela Apeagyei, who coleads IHME's health resource tracking team.

Only a handful of countries have been able to increase assistance to cushion the fallout from recent cuts. Nigeria approved an extra $200 million toward its health sector in February. Australia, Japan, and South Korea slightly increased their contributions to DAH: Australia by 3%, Japan by 2%, and South Korea by 4%. In the case of Australia, additional funding went toward strategically important countries in the Pacific and Southeast Asia and away from organizations such as the Global Fund, which invests in HIV, TB, and malaria programs.

China, maintaining its general contribution to DAH, also committed $500 million to the World Health Organization after the United States withdrew its commitments. Funding from the World Bank, the Gates Foundation, and regional development banks has remained relatively stable.

To Dieleman, the most troubling shift has been toward the politicization of aid.

"On a global scale, development assistance for health was almost universally accepted as a good thing—it wasn't politically controversial," said Dieleman. "All of a sudden, it's very squarely political and on the chopping block. That's not just a U.S. phenomenon. That's global."

This fall, the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria will hold its replenishment conference, where the organization will seek $18 billion to finance its operations through 2029. The United States has historically funded one-third of the organization's budget.

Dieleman does not hold high hopes for returning to the old landscape and instead forecasts a new normal. "Our models suggest things are pretty flat, they're not going up. From looking at budgets, I expect 2026 will be lower than 2025, and don't expect a rebound by 2030 in any way. I think we're going to flatline at a new low."

Whether the world is transitioning away from DAH permanently remains to be seen. "We live in a constantly evolving aid ecosystem these days," said Apeagyei.