A pattern woven throughout history reveals an unsettling truth: Although acute infections such as influenza and COVID-19 can devastate populations in the short term, their lingering effects—the so-called long flus of previous generations—have proven to be quiet killers.

Chronic conditions stemming from infections, whether labeled influenza nervosa, myalgic encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome, or long COVID, haunt individuals well after the initial illness subsides. Time and again, society has failed to reckon with these conditions, relegating their sufferers to the fringes of medical understanding and societal concern.

This trend is ancient. In 412 BCE, Hippocrates documented the Cough of Perinthus in a port city in northern Greece—the first known long flu, entailing "impaired night vision" and "paralysis of limbs." Many at the time perceived these symptoms as spiritual in nature, but Hippocrates was convinced that they were the physical manifestations of imbalanced humors: black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood.

Five centuries later, another Greek physician, Galen, built on this idea, categorizing human temperament based on the four humors: melancholy (black bile), hot tempered (yellow bile), laid back (phlegmatic), and hopeful (blood). The ancient Greeks may have been wrong on the fundamentals—lacking thousands of years of medical insights or comprehension of germ theory—but their instinct to connect illness and temperament can help frame how we think about health today.

Forgotten Postviral Illness With the Flu

Over the centuries, historians have chronicled how influenza devastated armies, gave rise to famines, and facilitated colonization of nonimmune populations. Fever, not the sword, conquered the armies of Roma and Syracuse in 212 BCE, as well as Charlemagne's troops in the ninth century CE. Even later, in 1557 as Queen Mary I presided on England's throne, 6% of her subjects succumbed to a flu epidemic before the virus traveled across the Atlantic to wreak havoc throughout the Americas.

Yet not until the Victorian era (1837–1901) did chronic conditions related to these flus capture the attention of science, the humanities, and fiction. These conditions would come to be known as postviral illness or syndrome—symptoms that last long after the body fights off an initial infection. According to medical historian Lakshmi Krishnan, protracted neurological effects of influenza were first idiomatically registered during this period and into the twentieth century. Such widespread chronic affliction earned the name influenza nervosa.

Their instinct to connect illness and temperament can help frame how we think about health today

As England reeled from the devastating fatalities of the 1847–1848 flu epidemic, a new virus from Siberia swept across Russia and Europe in 1889 and 1890. The initial mortalities in England gave way to enduring morbidities that included difficulty sleeping, numbness in the fingers and toes, memory lapses, cognitive impairments, impotence, psychosis, and heavy menstrual bleeding. That virus was deemed influenza nervosa for its lasting neurological impact.

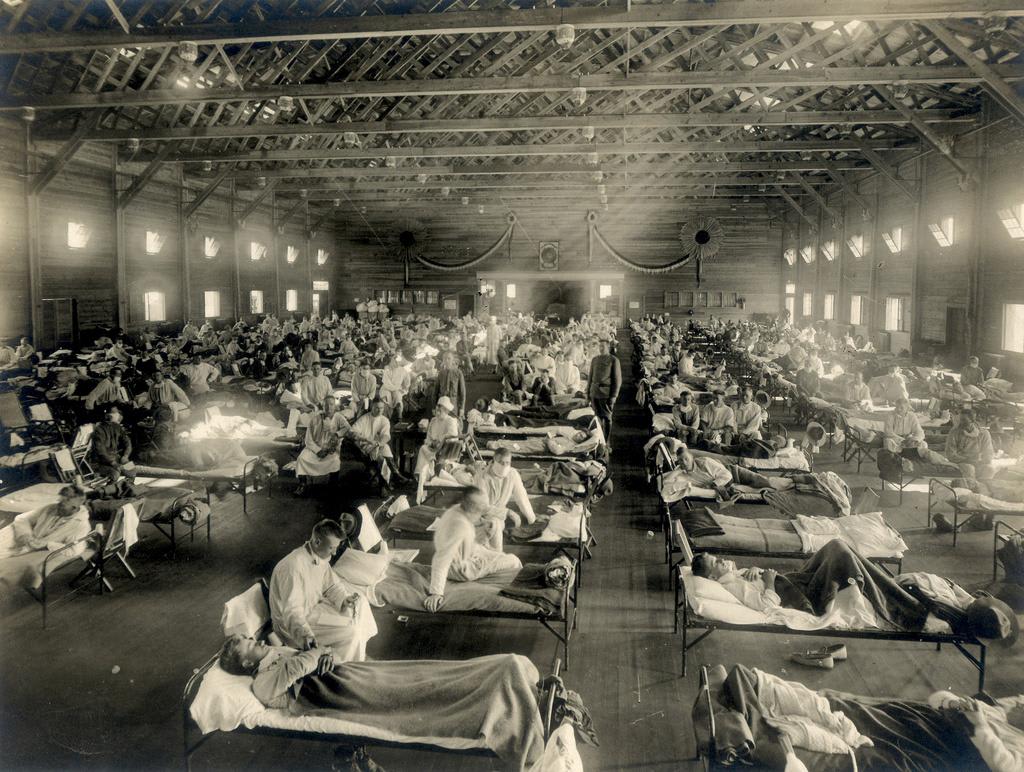

Broad neurological affliction was mirrored in the Spanish flu, or Great Influenza of 1918. Given its virulence and far-reaching devastation, historian John Barry suggests that had the pandemic not coincided with so many soldiers dying in the trenches during World War I, it might have become more than a footnote in history. Long-term debility is rarely discussed in relation to this influenza, even though hundreds of thousands across the globe suffered from encephalitis lethargica—a contemporaneous and possibly secondary inflammatory brain disease that threw many into a comatose-like state for years, and in countless cases, led to the neurodegenerative condition of post-encephalitic parkinsonism.

It was also the first time widespread chronic illness was recorded beyond the West. In Africa, death rates exceeded those in Europe, afflicting 2% to 5% of the population, and persistent symptoms—such as "loss of muscular energy" and "nervous complications"—were reported from South Africa to New Zealand. This postflu fatigue debilitated not only people but entire economies, as evidenced by the Famine of Corms, which arose in the region that is now Tanzania when such symptoms prevented farmers from cultivating their fields.

The Rise of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

These early accounts of prolonged postviral exhaustion—often neurological in nature—set the stage for an ongoing debate in the medical community surrounding the classification and underlying biological mechanisms driving myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. Before long COVID, these two terms dominated the discourse, downplayed as they were due to scientific ignorance and sexism.

In 1934, Los Angeles County General Hospital patients started reporting symptoms much like poliomyelitis (polio). At the time, polio was circulating throughout California, causing flu-like symptoms, long-term muscular weakness, and fatigue that was compared, and often confused, with myalgic encephalomyelitis. The public hospital treated 2,000 inpatients and 2,500 outpatients, and after the initial wave of infections, 198 hospital employees contracted a neurological illness, termed atypical poliomyelitis, affecting nearly 1 in 20 physicians and 1 in 10 nurses.

This health burden was much higher than those for polio. Six months later, 55% of hospital staff were not back to work. Researchers found that women were more likely to develop the mysterious condition, and the 21 individuals with the longest-lasting symptoms were all women reporting muscular pain, persistent fatigue, and cognitive changes. Several were given hysterectomies as treatment, premised on the notion that their uteruses had caused these "hysterical" symptoms.

Then in 1948, a disease that looked like polio broke out at a boarding school in northern Iceland before spreading to thousands across the region. Named after the school's town, Akureyri disease—what was later recognized as myalgic encephalomyelitis—caused long-term neurological issues in half of people who experienced severe acute illness during the initial outbreak. Many living with the affliction were identified as having a psychiatric disorder (or hysteria), much like the diagnoses at the Los Angeles hospital fourteen years earlier. A similar illness emerged a year later in Adelaide, Australia.

When another outbreak occurred in 1955 at the Royal Free Hospital in London, medical hypotheses began diverging. The 292 staff members hospitalized there were diagnosed with what was called Royal Free disease, later deemed myalgic encephalomyelitis. However, based on nerve stimulation testing of patients' muscles, some doctors suggested the condition was virus borne. Melvin Ramsay, MD, a consultant for infectious disease at the hospital, was particularly convinced that the outbreak stemmed from a virus, becoming so outspoken that the public started calling myalgic encephalomyelitis by the colloquial name, Ramsay's disease.

By 1970, two psychiatrists, Colin McEvedy and A. William Beard, had reevaluated the Royal Free Hospital outbreak, arguing that it was "mass hysteria." Observing that more females than males were afflicted and that no biological signs were evident, they pushed for the condition to be renamed myalgia nervosa—a term that, unlike influenza nervosa, carried greater psychosomatic implications given its emphasis on subjective muscle pain rather than postviral neurological disturbance.

Meanwhile, hospital staff, including Ramsay, continued to contend that the illness was caused by a virus. Ramsay's response [PDF] convinced some in the medical community that a biological—not psychological—explanation needed to be taken seriously, but this controversy left patients with chronic conditions in limbo for decades.

In 1984, yet another cluster of symptoms arose in the town of Tapanui on New Zealand's South Island. The media called it Tapanui flu after general practitioner Peter Grahame Snow concluded that the symptoms alongside prolonged and unexplained fatigue were the result of epidemic neuromyasthenia.

That same year, more than 100 people got sick in Lake Tahoe. Sparking a terminology debate, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) coined the outbreak chronic fatigue syndrome. Without biological markers, researchers had decided this was "more neutral and inclusive," despite myalgic encephalomyelitis being the dominant term since Ramsay's advocacy.

This new label outraged patients, who voiced their dissent [PDF] to the committee in charge of the decision. Advocacy organizations found that 85% to 92% of myalgic encephalomyelitis patients disapproved of the term chronic fatigue syndrome, complaining that it trivialized their condition and perpetuated stigma—namely unjustly aligning post-exertional malaise with malingering fatigue. By 2003, the official classification was combined into the mouthful myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, more commonly known as ME/CFS.

ME/CFS is particularly difficult to address given the variability of symptoms. Clinicians often identify depression as a defining feature, but patients maintain that their physical symptoms are rooted in a viral cause, pushing back against the dismissive trope "it's all in your head."

Past Is Prologue

The global COVID-19 pandemic has caused tens of millions of deaths worldwide, but within six months of Wuhan's December 2019 outbreak, reports surfaced of a post-COVID condition. By September 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed an International Classification of Disease for what later became known as long COVID. A year later, the WHO published an official case definition [PDF] of the chronic condition precipitated by COVID-19.

According to recent statistics, long COVID affects an estimated 6% to 11% of adults who have had the virus. The pandemic of acute COVID-19 may have been declared over in May 2023, but the pandemic of its chronic aftereffects still rages on.

Modern science has not fully accepted that viral infections can seed long-term neurological and systemic disorders. The emerging evidence that COVID-19 could trigger neurodegeneration forces us to look back at history's warnings. Although RECOVER studies aimed at solving long COVID received $1.15 billion from Congress in 2020, little headway has been made toward scientific consensus, and research has been made ever more difficult by President Donald Trump administration's dismantling and politicization of key public health agencies.

Society cannot afford to dismiss long COVID as a niche or exaggerated condition, or ignore its striking parallels to the secondary symptoms of the Spanish flu and postviral syndromes that have emerged throughout the centuries. If history repeats itself, as it so often does, this failure to act could culminate in a silent pandemic of disability and neurodegenerative disease, one that will strain our health systems, economies, and communities for decades to come. Long COVID may have attracted more mainstream attention than other postviral conditions, but the response remains fragmented and inadequate given the breadth of its impact and the potential for long-term societal harm.

The interconnectedness of the twenty-first century world and virulence of potential future pandemics, such as bird flu or pathogens engineered by artificial intelligence, only increases the stakes. Recognizing long COVID as part of an ongoing historical pattern is the first step in breaking a dire cycle. But the real challenge is applying this knowledge—to accelerate research, reframe medical diagnostics, and ensure that the lessons of the past serve those still living rather than remain buried beneath all the bodies.