The global HIV response is at an inflection point. For the first time, a twice-yearly injection—lenacapavir —offers a real chance to transform prevention. Trials show that the drug prevents infections in 100% of females and 96% of males; additionally, new access agreements announced in late September by the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) and partners during the UN General Assembly could make the drug available at an affordable price ($40 per year) across more than 100 low- and middle-income countries by 2027.

This progress is welcome, but without equity, it is fragile. If long-acting prevention is to change the trajectory of the HIV epidemic, it needs to begin with those at highest risk.

The November 18 announcement from the U.S. State Department—confirming that the first shipments of lenacapavir have already reached Eswatini and Zambia and will be administered immediately—is a defining moment. For the first time, a HIV prevention injection is arriving in Africa the same year it was approved in the United States, setting a new bar for speed, coordination, and political will. As an African, that makes me proud. But speed alone is not equity.

The America First strategy marks an important recommitment by the United States to global HIV prevention, but does not translate this political signal into the operational steps needed to roll out long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication such as lenacapavir. The new U.S. strategy offers high-level direction but does not outline country-level targets, regulatory pathways, service delivery models, or guidance for integrating lenacapavir into national systems.

These elements must be defined by countries themselves. National governments will need to set ambitious goals for scale-up because the widely cited figure of reaching 2 million people in three years is only the minimum required to maintain pre-2025 PrEP trajectories and prevent backsliding. Accelerated regulatory reviews, updated national guidelines, investment in community-led delivery models, and front-loaded procurement will all be essential to ensuring a timely and equitable introduction of long-acting PrEP.

Forecasting Needs

This year, Global Black Gay Men Connect (GBGMC) partnered with AVAC and Avenir Health to produce the first global forecast of long-acting PrEP demand across 172 countries. The findings are stark. By 2030, the world will require 11.5 million person-years of PrEP annually to meet prevention needs—a measure that reflects how many people are protected by PrEP and for how long. If long-acting modalities, that is, drugs that release slowly over time, become the dominant form of PrEP treatment, cabotegravir would account for 3.0 million person-years and lenacapavir for 2.4 million, oral daily and monthly pills making up the balance.

Of the people most at risk for HIV, men who have sex with men (MSM) will require nearly 7 million person-years of PrEP annually. Transgender women, sex workers, and people who inject drugs account for most of the rest. Altogether, nearly 60% of global PrEP demand will be concentrated in groups that bear a disproportionate share of HIV incidence, including gay and bisexual men, sex workers, transgender people, people who use drugs, and other communities historically underserved by national health systems.

The science is advancing; the delivery is not

These numbers tell a simple truth: There is no path to ending HIV without investing in the people who bear the greatest burden.

GBGMC's recent market assessment reinforces that reality: Despite progress in expanding access to PrEP, new HIV infections continue to occur disproportionately among MSM, transgender people, sex workers, and people who inject drugs due to structural barriers that block access to medications, such as criminalization, stigma, and underfunded services.

Yet the assessment also makes clear that governments and donors are not starting from zero: In many countries, the infrastructure, policy frameworks, and community-led delivery models are in place.

The Consequences of Delay

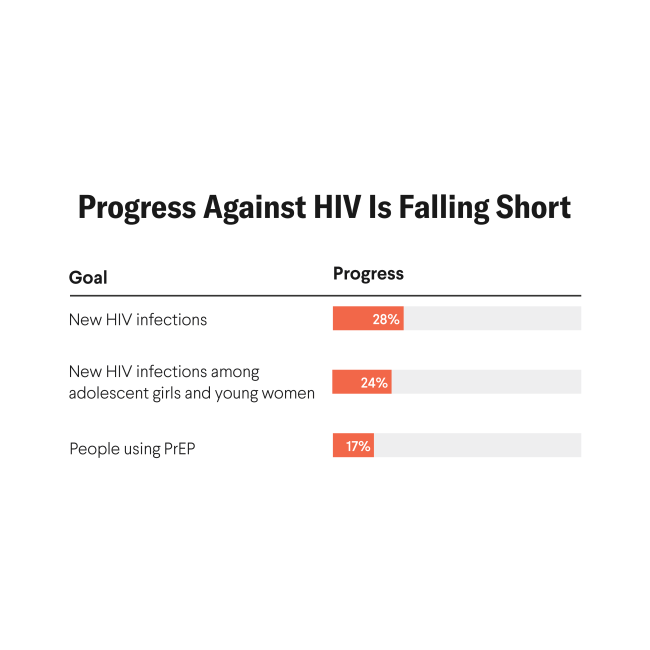

Despite more than a decade of oral PrEP availability, fewer than 4 million people worldwide currently use it—far short of UNAIDS' 2025 target of 21.2 million. In 2024 alone, 1.3 million people contracted HIV, virtually the same number as the year before. The science is advancing; the delivery is not.

Delays in regulatory approvals threaten to deepen access gaps. Among the eight early-adopter countries identified for rapid introduction, only the United States, South Africa, and Zambia have approved lenacapavir for HIV prevention as of November 2025; the remaining countries remain in pending or preparatory stages, and long-acting PrEP is still absent from most national HIV guidelines. Every year of delay translates into thousands of preventable infections.

GBGMC's market assessment shows this pattern clearly. The antiretroviral medication cabotegravir is now approved in more than 50 countries, yet national rollout remains slow. Generics for both cabotegravir and lenacapavir are not expected before 2027, creating affordability bottlenecks.

According to GBGMC's Frozen Out report, donor instability has already triggered widespread service disruptions: In the South-South region of Nigeria, five key population clinics have shut down, cutting off access to antiretrovirals (ARVs), PrEP, condoms, and lubricants. External reporting that summarized the findings estimates that approximately 800 people in that region lost access to these services when the clinics closed. In Kenya, safe-space community centers are on the verge of closure; in Uganda, key population antiretroviral therapy clinics are being folded into public facilities, where stigma is higher against HIV patients. These disruptions halt safe spaces, interrupt PrEP access, and erode the trust between communities and health providers that is essential for any rollout to succeed.

Recent modeling underscores the stakes. A one-year pause in PrEP funded by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) could result in 6,671 additional new HIV infections, including more than 5,600 among key populations. Tanzania, Nigeria, South Africa, Zambia, and Uganda could account for 68% of the total impact.

The ripple effect could push the total number of infections above 10,000 over five years. That is not a hypothetical scenario. It is a reminder of what happens when politics and budgets move faster than science and delivery.

Data alone cannot close gaps—governments need actionable plans. In 14 countries, national "last mile" processes have generated costed and validated strategies for integrating key population services. One example is South Africa's Last Mile Key Populations Plan. The country has a fully costed strategy that expands key populations–friendly centers of excellence; integrates PrEP, injectable PrEP, and lenacapavir into the public system; and transitions thousands of key population clients from donor-funded drop-in centers into government clinics.

In Gauteng, South Africa alone, 6,882 clients were transferred, 4,847 were successfully reengaged, and 724 were registered in public clinics—demonstrating that transition pathways can work. The same plan outlines national rollout of cabotegravir, preparation for lenacapavir in 2026, and full integration of harm reduction and gender-affirming services into public facilities. These are practical tools, developed with governments and communities, that demonstrate how scale-up can happen now. What is missing is not readiness, but the political will and financing to act.

The United States cannot—and should not—be the sole driver of long-acting PrEP access worldwide. But neither should its role be understated. It remains the only global actor with the resources, diplomatic reach, procurement power, and technical infrastructure to coordinate an introduction of this scale. The point is not to diminish U.S. leadership, but to recognize that no single country can carry this effort alone.

National governments should take ownership of regulatory reviews, guideline updates, and health system readiness, and communities everywhere should reimagine service delivery models that meet people where they are. At the same time, the world needs to envision a model where the United States is not the only engine of progress, but instead a committed partner in a shared global effort. Without U.S. leadership to align donors, derisk early procurement, and maintain political momentum, the rollout would move far more slowly—but lasting, equitable access will depend on countries and communities working alongside, not behind, the United States.

A one-year pause in PEPFAR-funded PrEP could result in 6,671 additional new HIV infections

In our assessment, 78% of key population-led organizations across 21 countries reported direct service interruptions following U.S. budget cuts. Community-led clinics, pharmacy-based prevention pilots, and human-centered demand generation are not theoretical—they are already working. Unless donors and governments invest in these key population-led models, long-acting PrEP will remain stuck in demonstration projects while infections climb.

Donors and governments are at risk of repeating old mistakes. Oral PrEP was rolled out primarily through general population programs, often bypassing the very communities at highest risk. The result was high uptake among lower-risk groups and sluggish progress where the epidemic was actually concentrated. Lenacapavir could fall into the same trap unless priorities shift.

Changes Ahead

CHAI's announcement provides clear evidence that global market conditions can be reshaped. When early signals, coordinated planning, and collective pressure align—reinforcing what communities have long argued: Access is a political choice, not an inevitable outcome. The next step to ensure access requires donors that make targeted investments, governments that act swiftly, and communities that lead the way. If the United States and its partners want to preserve credibility in global health, they need to show that this time will be different.

Researchers are studying a monthly oral pill, which could offer a middle ground between daily PrEP and injectables, and ultra-long-acting implants that might provide protection for a year or longer.

New digital health tools are also emerging—AI-powered chatbots, virtual counselors, and self-care apps that can empower people in key populations to assess risk, learn about options, and link themselves to care discreetly and safely. When paired with these biomedical innovations, digital tools could close gaps in knowledge, trust, and access.

Together, these innovations represent a prevention science revolution—offering more choice, flexibility, and autonomy for people at risk. The task now is not just to welcome new science, but also to build delivery systems that ensure every breakthrough reaches the communities who need them most.

Lenacapavir has rightly been celebrated, but breakthroughs do not save lives on their own. Without equity at the center, countries risk turning a scientific milestone into another story of squandered promise.