Calls to reform the global health system have moved from theory to necessity. The sharp contraction in international health financing has intensified this shift, turning what once felt like incremental change into a matter of urgency as organizations are forced to make difficult choices about priorities, mandates, and efficiencies.

At the same time, vital programs are being reduced or cut outright. Interrupted treatment programs, stalled prevention campaigns, and growing uncertainty for health workers and people seeking care are projected to result in nearly 10 million additional deaths by 2030.

These shifts have irreversibly shaken the foundations of global health. But with this challenge comes the opportunity to build stronger mechanisms to support the responsible transition to country-owned, resilient health programs—ones grounded in sustainability and efficiency.

Numerous emerging initiatives present reform perspectives. They highlight necessary shifts: to mobilize domestic resources, prioritize impact and efficiency, rebalance health priorities, address systemic challenges, and promote primary health care aligned with population needs. Most of these initiatives promote the concept of global public goods [PDF]—shared investments that provide a collective benefit that no country can achieve alone, such as regulatory standards and disease surveillance.

Yet, as reform efforts accelerate, discussions are increasingly dominated by institutional consolidation and mandates. These conversations may deliver short-term efficiencies, but they leave a critical dimension dangerously underdeveloped: how the future global health system ensures equitable access to innovation. Without a deliberate mechanism to anticipate, shape, and scale access, emergency decisions made under funding pressure risk crystalizing into tomorrow's broken system.

Innovation Has Driven Progress—But Equity Is Not the Default

Innovation has been one of the main drivers of global health progress over the past two decades. Breakthrough medicines for HIV, more effective tuberculosis (TB) treatments, lifesaving vaccines, and rapid diagnostics for infectious diseases have saved hundreds of millions of lives, strengthened health systems, and helped economies grow—laying the foundations for an unprecedented response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

But innovations do not move from research into health systems by default. They move through markets that reward purchasing power, infrastructure, and early demand. If left unmanaged, innovations often widen the very gaps that global health claims to close, increasing inequalities between and within countries.

The recent landmark pricing agreement for lenacapavir—a revolutionary long-acting injectable for HIV prevention—illustrates both the risk and the opportunity inherent in this moment. Without deliberate intervention, access to a breakthrough technology of this kind would likely have followed familiar patterns—reaching high-income markets first, while affordability and availability in lower-income settings lagged behind for several years.

Instead, early coordination and market-shaping efforts by Unitaid, the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), and Wits RHI helped secure an unprecedented pricing deal with Dr. Reddy's Laboratories to supply a generic version of lenacapavir at $40 per person annually for 120 low- and middle-income countries. The deal shows that when access is planned early, affordability does not have to lag behind innovation. The same dynamic applies across diseases and technologies. Without deliberate action, even the most promising innovations can fail to reach those who need them most.

Countering these and other market failures requires long-term and large-scale investment, early risk-taking, market-shaping across regions and countries, and globally coordinated planning for equitable access—capacities that extend well beyond the mandate or means of any single country.

Access as a Global Public Good

These market failures demonstrate why access cannot be treated as an afterthought—or a matter of charity. It must be treated as a core function of the global health system and financed as a global public good.

The deal shows that when access is planned early, affordability does not have to lag behind innovation

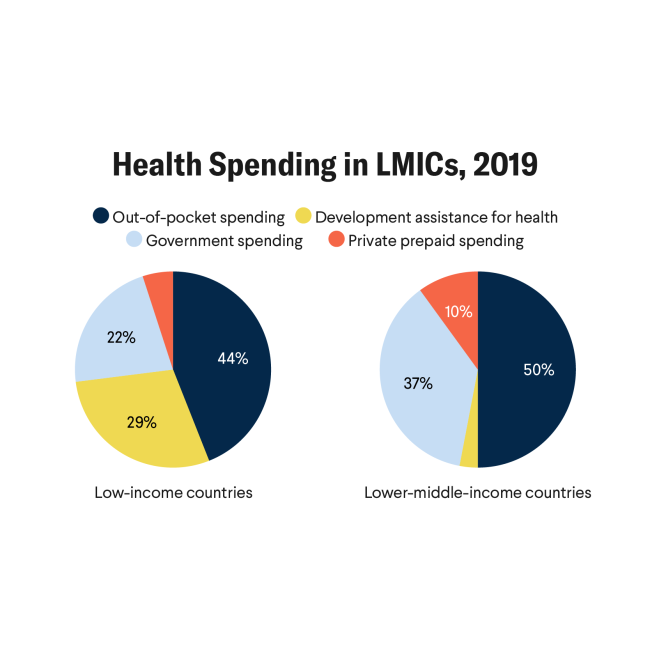

Yet today, global public goods in health remain chronically underfunded and undervalued. Countries are quickly transitioning toward more self-reliant, domestically financed health programming, driven by dramatic shifts in the international aid landscape. But without strong international collaboration and investment to support access to innovations as a collective good, the bridge between the two will collapse—leaving countries to navigate complex markets, negotiate prices, and introduce technologies on their own, often from a position of weakness.

For these reasons, multilateralism must evolve, not retreat.

The Global Health System of Tomorrow Needs an Innovation Accelerator

What is needed is a new kind of multilateral platform for access to innovation, designed for today's challenges. Positioned between late-stage research and large-scale rollout, it would focus on one essential task: making sure that lifesaving health tools reach all populations who need them, not just those who can afford them. By identifying the most relevant innovations emerging across regions, shaping markets early, supporting technology transfer and sustainable regional manufacturing, and extending coverage to underserved countries and communities, such a platform could dramatically reduce prices and speed up access at scale.

To be fit-for-purpose, this approach must move beyond narrow disease-by-disease responses and instead align with country and regional health priorities. By analyzing demand across geographies, identifying promising products early, and investing where national markets cannot, it would ensure that innovation delivers equitable impact—operating with the legitimacy, neutrality, and scale that only a multilateral partnership can provide.

No institution occupies this exact role, but experience shows this model works. For the past 20 years, Unitaid has played a leading role in bridging the innovation-access divide, helping to introduce more than 100 health products with a return on investment of 46 to 1—making this model among the most cost-effective in global health.

Our approach—grounded in science and evidence, focused on equity and access across the value chain, and supported by inclusive partnerships, agile multilateral governance, and financial and operational autonomy—provides a strong foundation. To meet current challenges, it would need broader disease coverage, strengthened country and regional representation, and a more diversified and stable financing base.

At a moment when trust in multilateralism is eroding and geopolitical tensions are reshaping development priorities, recommitting to this approach is not idealism, it is pragmatism. Without mechanisms to ensure affordable access to innovation, efforts to build country self-reliance will falter. As countries face high prices and fragmented markets on their own, health budgets will come under increasing strain, undermining sustainability and leaving systems more exposed when shocks occur.

The choice facing global health is stark. Its leaders can continue to celebrate innovation while tolerating exclusion, accepting a world where scientific breakthroughs coexist with avoidable suffering. Or they can redefine access as a shared responsibility, invest in it as a global public good, and reshape the multilateral mechanisms needed to connect discovery to delivery.