Washington rewards headline numbers. Fifty billion dollars. But the real story of the new foreign affairs spending package lives beneath the top line—in the oversight requirements, the embedded policy signals, and a quiet redesign of global health diplomacy. The new appropriations reflect a moment of transition, carrying structural policy shifts that will shape how the United States engages globally for years to come.

On February 3, President Donald Trump signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2026, which incorporates the National Security, Department of State and Related Programs (NSRP) appropriations bill for the current fiscal year and its accompanying explanatory statement. Originally released by the House Appropriations Committee on January 11, the legislation replaces what was historically known as the State and Foreign Operations account and now anchors the core architecture of U.S. global health financing and governance.

Let's start with the arithmetic. The enacted package totals roughly $50 billion, about 16% below last year, yet nearly $20 billion above the White House's proposed budget. In most years, this cut would ignite a political firestorm. But against the backdrop of proposed deep reductions to global health, Congress—on a bipartisan basis—drew a line. For millions of people, and for countries that depend on American partnership, it is a moment of reprieve.

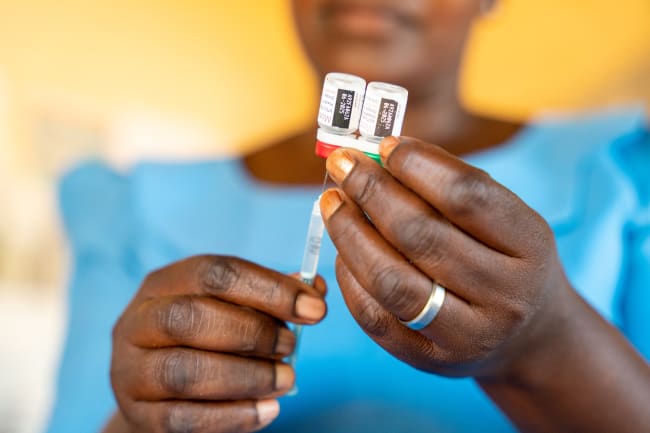

Within the $50 billion envelope, global health receives about $9.4 billion through the Global Health Programs (GHP) account, representing the bulk of U.S. global health assistance and a $615 million decrease (−6%) compared with fiscal year 2025. As reported by KFF, most health accounts were either reduced or held flat. Humanitarian assistance totals $5.4 billion, and $6.77 billion flows to national security investment programs. Meanwhile, Gavi receives $300 million for its vaccine alliance—unchanged from the previous year despite the administration's push for deeper reductions. The latter funding maintains a steady, if modest, U.S. commitment to global immunization.

The deeper story lies in the policy language—and in what Congress is signaling about the future of U.S. global health leadership

Within the global health portfolio, approximately $5.9 billion is directed to HIV/AIDS programs, reaffirming the centrality of the infectious disease within U.S. global health policy even in a constrained fiscal environment. This segment includes $4.6 billion for the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR); $1.3 billion for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; and $45 million for the Joint UN Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

The top line suggests continuity, but the underlying structure reveals recalibration—the Department of State's role expands whereas the former funding line for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) effectively disappears. The Global Fund contribution falls by roughly 24%, although this decline aligns with burden-sharing formulas tied to the replenishment cycle and the U.S. pledge rather than signaling a strategic retreat.

Taken together, two conclusions stand out. First, bipartisan support for global health endures—even in a chaotic and deeply polarized Congress. Second, lawmakers have clearly rejected the scale of reductions proposed by the Trump administration, preserving core global health investments despite intense pressure to cut deeper.

But the numbers alone do not explain these appropriations. The deeper story lies in the policy language—and in what Congress is signaling about the future of U.S. global health leadership. Before getting there, a bit of context. As a former congressional staffer who worked for an appropriator, I can say this: Spending bills are not typically vehicles for heavy policy. They set funding levels, impose restrictions, and require reporting. What they usually do not do is reshape governing structures, rewrite operational authority, or embed a long-term policy orientation. The new law does.

As I wrote on my Substack—Lights, Camera, Equity—three major themes stand out.

The first is authority consolidation. The legislation reinforces the ongoing shift of operational gravity toward the Department of State. Strategy, reporting, coordination, and bilateral engagement are increasingly routed through diplomatic channels rather than the traditional ecosystem centered on development agencies and implementing organizations, both for-profit and nonprofit international organizations.

Congress did not repeal the statutory authorities of the U.S. Agency for International Development, but it also did not meaningfully fund them—an outcome that, in practice, shifts operational power without formally rewriting the law. At the same time, the State Department's influence over global health and development is expanding dramatically, positioning it as the central actor shaping strategy, financing architecture, and bilateral engagement.

The legislation repeatedly directs the State Department, not USAID, to design and submit the transition strategy for PEPFAR; oversee global health compacts and bilateral agreements; coordinate grants, loans, development finance institutions, and multilateral development banks; manage post-transition engagement; and report directly to Congress on benchmarks, funding trajectories, and contingencies. In other words, development and diplomacy are now operating as fused instruments of statecraft.

The second theme is the evolution of PEPFAR—and the end of HIV exceptionalism. The bill directs a phased transition toward greater country ownership, requiring clear benchmarks, sustainability planning, and co-financing expectations. HIV is no longer treated as permanently exceptional within U.S. global health architecture.

PEPFAR is not being repealed. What is changing is its trajectory.

To be clear, PEPFAR is not being repealed. What is changing is its trajectory. Congress now explicitly directs the Secretary of State to submit "a comprehensive strategy to guide the structured transition of PEPFAR-supported programs to country-led ownership," alongside a gradual reduction in reliance on U.S. bilateral funding in countries deemed ready for transition.

That framing marks a fundamental shift. PEPFAR is no longer governed as an open-ended emergency response. It is being managed as a program expected to move—deliberately, systematically, and measurably—toward domestic sustainability. In this sense, PEPFAR is being repositioned as the template for how major U.S. global health programs evolve from externally financed interventions to nationally sustained systems.

Third is the congressional codification of the America First Global Health Strategy. For the first time, Congress explicitly references and acknowledges this strategy within appropriations language—an institutional milestone and a clear policy win for the administration's approach.

But the recognition comes with conditions. The legislation compels detailed reporting on the implementation of global health compacts and bilateral agreements negotiated under the America First framework. Crucially, Congress requires greater transparency around these bilateral deals—or memoranda of understanding (MoUs), ensuring that transition plans, financing expectations, and performance benchmarks are visible to congressional oversight bodies. This transparency requirement introduces accountability into a process that will shape billions of dollars in health investments and the future structure of national health systems.

Last, the erosion of data visibility is a growing concern. For two decades, rigorous data, open reporting, and measurable outcomes have been hallmarks of the U.S. global health approach—especially under PEPFAR, where performance, transparency, and public data helped drive progress and sustain bipartisan support. Yet the administration has halted routine public release of PEPFAR data and planning documents over the past year. What's more, the recent bilateral agreements have been negotiated with limited visibility, and key data systems and reporting channels have been switched off.

Without a meaningful pivot back toward transparency and accessible data, it will become far more difficult for global health actors, congressional supporters, and implementers to track progress, evaluate impact, and sustain confidence in the system. In a model increasingly built on transition, co-financing, and shared responsibility, diminished data visibility is not a technical issue—it is a strategic risk.

Taken together, this legislation marks a turning point. U.S. foreign assistance is entering a new phase—leaner budgets, stronger reliance on national government capacity and accountability, and a sharper U.S.-first orientation. Global health—and HIV in particular—remains protected but no longer structurally exceptional. It is now embedded within a broader architecture of diplomacy, finance, and national interest.

Politically, the foreign affairs appropriations reflect a recalibration of power. Congress restored funding above the administration's request, embedded transparency, and asserted oversight, while the administration secured formal recognition of its global health strategy. Both branches achieved key objectives. The real test now shifts to implementation.

Two warning signs bear watching. First, institutional capacity remains an open question. As authority consolidates at the Department of State, the ability to operationalize expanded responsibilities will determine whether this new architecture succeeds in practice, not just on paper. Importantly, the bill requires coordination with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on global health activities and establishes a Prevention, Treatment, and Response Initiative to support the research, development, and delivery of vaccines and other prevention technologies.

Second, whether the Office of Management and Budget seeks to slow or constrain spending over time remains a risk. However, the appropriations language is unusually clear: Funding "shall be made available at not less than the amounts specifically designated" in the explanatory tables, and the administration is explicitly prohibited from deviating from the global health funding levels set by Congress. This measure provides an important guardrail against future erosion.

The real question is not whether the United States stays in the fight. It is whether this swiftly redesigned system can continue to deliver—at scale and where it matters—while preserving the spirit of American generosity and partnership that has shaped global health progress for decades and made the United States a force for hope around the world.