As we embark on 2026, the global health landscape looks markedly different from the one that defined this century.

The era of expansive U.S. global health leadership and large-scale Group of Seven (G7) development spending has ended. Donor budgets are contracting sharply. Climate shocks, conflict, migration, and economic instability are driving demand for health services faster than countries can finance or staff them. Health systems everywhere remain overstretched, under-resourced, and critically short of workers.

This moment was bound to force a reckoning. But instead of producing clarity, the leadership and funding vacuum has triggered a surge of disconnected reform efforts—each well-intentioned, each claiming to put countries in the driver's seat, and collectively at risk of deepening the very fragmentation they aim to fix.

Sovereignty without multilateral cooperation is not sovereignty at all

Amid this proliferation, a narrative has taken hold: That expanding country sovereignty must come at the expense of traditional multilateralism. This is a false and dangerous choice. Sovereignty is not only essential; it is long overdue. But sovereignty without multilateral cooperation is not sovereignty at all. No nation, however capable, can prepare for pandemics, climate shocks, displaced populations, or supply-chain vulnerabilities alone.

The work ahead is not to pick sides but to design a global health architecture where sovereignty sets the agenda and multilateralism enables it.

A Proliferation of Initiatives, but No Coherent Map

Over the past year, the global health sector has launched or revamped a dizzying array of initiatives:

- The Accra Reset is led by African governments to redirect development finance toward nationally defined priorities.

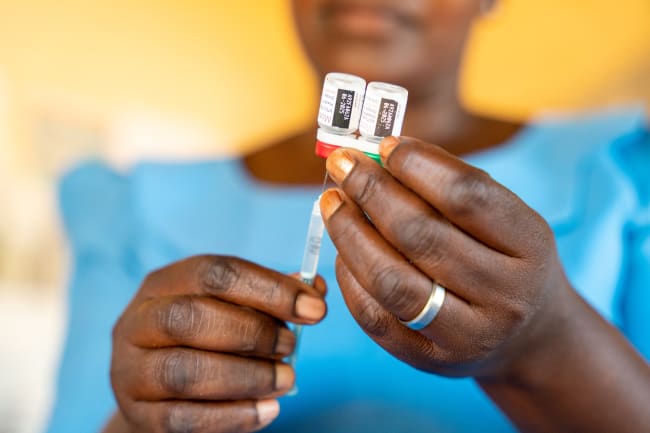

- Gavi's LEAP operating model promises greater country leadership over immunization financing and delivery.

- The World Bank's National Health Compacts aim to align the bank's and partners' financing behind country-owned health investment plans.

- The Lusaka Agenda advocates for the integration of global health initiatives and reduction of duplication.

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention's Health Financing in a New Era aims to revamp national health-financing plans and increase national sovereignty for African nations.

- The Global Fund's climate-health integration supports responding to climate-induced health emergencies while building low-carbon, climate-resilient health systems.

- The America First Global Health Strategy [PDF] emphasizes mutual accountability, in part through a new wave of bilateral agreements.

Each initiative responds to a real need. But they do not actively integrate with one another, and they do not form a unified strategy. Instead, they ask already overstretched ministries to navigate multiple methodologies, reporting cycles, and "priority" frameworks—often amid emergencies.

The global community is telling governments to lead while overloading them with competing demands. This is framed as sovereignty, but it functions as administrative paralysis.

Worse, these frameworks frequently reinforce artificial trade-offs: prioritize pandemics or primary care, climate resilience or maternal health, health workforce or digital infrastructure. In reality, these are not competing agendas but inseparable components of a functioning health system. Fragmented initiatives inevitably produce fragmented implementation. Disease-specific financing has led to parallel datasets, supply chains, super-specialized health workers, and lost opportunity for more horizontal gains in universal health coverage, for example.

A Simple Test for Governments Navigating a Crowded Landscape

In this post-2025 moment, countries are being presented with more initiatives, more partners, and more offers of support. The risk is slipping back into fragmented and duplicative pathways shaped more by donor priorities than by national ones.

Countries must lead in this next phase of global health redesign. They are best positioned to understand why past efforts fell short and what will be required for long-term success—success defined by sustained financing, increased access to quality care, resilience, and improved health outcomes.

What's needed now is a practical way for countries to assess the value of each initiative as the new efforts define their mandates in service to countries. Five questions can guide collaboration and decision-making:

- Does this initiative align with and advance the national health strategy? If it doesn't, it's a distraction.

- Will it strengthen domestic financing and fiscal space in the long run? Short-term funding that creates long-term dependency comes at a cost.

- Does it build the health workforce that the country actually needs? No initiative enhances sovereignty if it bypasses doctors, nurses, midwives, and other essential health workers.

- Does it strengthen and simplify a country's ability to govern, regulate, and manage the system? Partners should help strengthen governance, not become the ones steering decisions.

- Will the system it builds endure when donor and partner attention shifts elsewhere? If the answer is no, the gains are unlikely to last.

This rubric is simple by design. Overcomplication is part of the problem, and clarity must be part of the solution.

Rwanda's experience offers a glimpse of what this can achieve. Donor alignment behind a coherent, government-led health-sector plan—beginning in the late 2000s—enabled rapid expansion of primary-care coverage, development of a skilled health workforce, and resilience in the face of regional shocks. A clear example is the marked drop in Rwanda's maternal mortality ratio [PDF] by 77% between 2000 and 2013. The principle is universal: strong national plans attract aligned investment; fragmented plans invite fragmented support. The marked improvements in health outcomes spoke for themselves.

Multilaterals Must Become Enablers of Sovereignty, Not Obstacles to It

Multilateralism is not obsolete, but it should evolve. The multilateral system of the future should be smaller, smarter, more agile, and explicitly designed to reinforce, not dilute, national sovereignty. That means the following:

- pooled, multiyear, flexible financing aligned with country plans

- investment in global public goods such as surveillance systems, supply chains, and research

- country-defined measures of success, and

- acknowledgment by multilateral stakeholders that global institutions need to evolve.

Some institutions are beginning to shift. Gavi's acknowledgment that its long-term success depends on countries eventually supplanting its vaccine campaigns is a meaningful step. But this mindset must become the norm, not the exception.

A New Compact for the Post-2025 World

The world is entering a new era. The aid paradigm that defined the first quarter of the twenty-first century is gone. A new order is emerging, one that should be shaped by country leadership, regional cooperation, and a reimagined multilateralism that recognizes the need to invest in global public goods, including health.

The world does not need more competing initiatives or newly branded global-health investment structures that remain donor-driven. It needs coherence, approaches that respect sovereignty, and a global health architecture worthy of the challenges ahead.