Global health actors often describe certain populations as hard to reach. These communities are often located in geographically remote or conflict-affected regions where the delivery of essential health services is described as logistically challenging. But the phrase hard to reach has become a euphemism that obscures the infrastructural, political, and historical dynamics that determine who does and does not receive care.

The Zero-Dose Divide

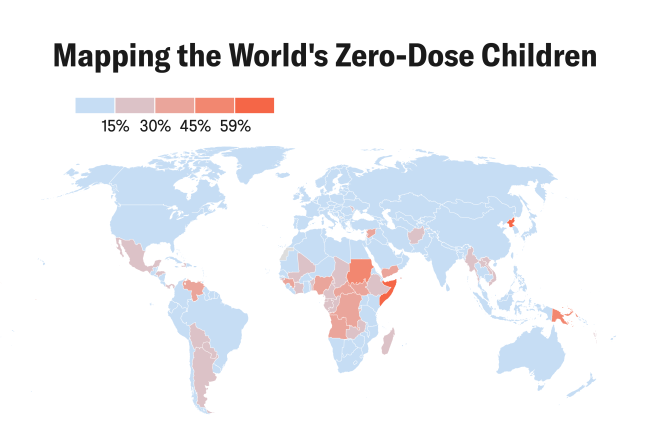

The term zero dose refers to children who have not received any routine vaccinations, particularly the DTP1 (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) vaccine. Sub-Saharan Africa hosts 60% of the global zero-dose population, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, and Nigeria being among the highest-burden countries. Since 2023, more than 12.7 million children in Africa have missed out on one or more vaccinations over three years. Most of these children live in low-and middle-income countries, especially areas characterized by fragility, conflict, displacement, and extreme poverty.

In Cameroon alone, approximately 130,000 children have been identified as zero dose since 2019

In Cameroon alone, approximately 130,000 children have been identified as zero dose since 2019. In the capital, Yaoundé, 37% of children age 12 to 59 months are fully vaccinated according to the national EPI (Expanded Programme on Immunization) schedule. But in remote areas of the northwest and southwest regions, access remains severely limited. These gaps often correlate with multiple deprivations that include low maternal education, inadequate health worker density, poor road infrastructure, and increased prevalence of political violence. Thus, zero-dose status is not merely a health indicator, but also a marker of broader sociopolitical exclusion.

The UNICEF-WHO Immunization Agenda 2030 (IA2030) calls for leaving no one behind, yet global immunization strategies continue to cluster around urban centers, conflict-free zones, and infrastructurally accessible regions. Beyond individual characteristics, spatial marginalization plays a major role. Communities several kilometers from paved roads with poor mobile network coverage and little presence of state institutions are significantly more likely to be overlooked.

Furthermore, data from Cameroon's Ministry of Public Health [PDF] shows a significant drop-off in immunization coverage as one moves from Yaoundé and Douala toward the Anglophone regions and rural northern districts.

Why Hard to Reach Misses the Point

Recent research argues that the term hard to reach distracts from systemic accountability, subtly shifting the burden of access onto marginalized communities rather than the national and global health systems meant to serve them. It fails to ask why populations remain unreached, and instead shifts the burden onto the communities themselves to be reachable. It disguises the complexity of why certain populations remain unreached—not because they are inherently isolated, but because of calculated decisions that deprioritize them [PDF]. These communities remain out of reach only insofar as the political will to reach them has been absent.

In Cameroon, this framing has a long shadow. The Anglophone regions, where today's vaccination gaps are deepest, were marginalized after the colonial partition of each country and sidelined after independence. Roads, hospitals, and clinics were unevenly distributed, leaving capital-adjacent zones prioritized for investment and peripheral conflict-affected or rural areas behind.

The Eyumojock Health District: A Case Study

Situated in Cameroon's southwest region, Eyumojock is a politically unstable and critically underserved area. The area has seen intensified conflict since 2016, when long-standing tensions between Anglophone and Francophone regions erupted into violence. The International Crisis Group reports that security forces have committed human rights violations, including the killing of civilians and destruction of villages, and that separatist groups have also perpetrated violence, further destabilizing the region.

In response to the deteriorating health-care infrastructure, mobile clinics were deployed to serve conflict-affected communities in the northwest and southwest regions, including areas like Eyumojock. These clinics often operate under challenging conditions, navigating poor road networks and security threats to provide essential services such as vaccinations, maternal care, and treatment for communicable diseases.

Health workers in Eyumojock describe journeys that involve hours of walking, river crossings on foot, and improvised mobile clinics in churches or abandoned schools. Even when vaccines are available, extended lockdowns and the emergence of ghost towns prevent many mothers from bringing their children for scheduled vaccinations, and many do not return once conditions improve. The situation in Eyumojock and similar districts highlights the broader implications of the zero-dose phenomenon of children missing out on routine vaccinations because of compounded barriers such as political instability, infrastructural deficits, and socioeconomic challenges.

The geography of unreachability in Cameroon is not accidental. The Anglophone regions, including Eyumojock, have historically received less public investment than Francophone areas. This disparity can be traced back to the colonial partition of Cameroon between Britain and France under League of Nations mandates after World War I, and the subsequent marginalization of Anglophone regions postindependence..

Regions like Eyumojock are not hard to reach because of nature or happenstance: They are unreached by design, positioned outside developmental priorities and state concern. Labeling them as hard to reach overlooks the systemic neglect and political choices that have led to their current state of infrastructural deficiency.

Improvising Care

In Eyumojock, as in other neglected spaces, care persists, but takes unrecognized forms. Health workers speak of climbing hills with coolers of vaccines balanced on their heads and using their personal phones to track missed children. Women in Eyumojock have established informal maternal health collectives, pooling funds and organizing transport for immunization visits when they hear of a temporary presence of vaccines. The children of Eyumojock and of countless other districts like it, though, are not hard to reach. As caregivers and health workers make their way through flooded paths and contested borders, what is required of the global health community is a radical approach of who and what is centered in health planning.

Hesitancy versus Inaccessibility

In the United States, the central challenge of immunization today is no longer supply but trust. Vaccine hesitancy, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a "delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services," has surged in the past decade. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that 36% of U.S. adults believed the risks of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh the benefits. Additionally, rates of routine immunizations among U.S. kindergartners continue to decline across all major vaccines.

Already, 2025 has seen spikes in measles cases in states with high exemption rates, underscoring the cost of manufactured doubt in the Global North. This trend has been linked to the convergence of social media disinformation, eroded trust in public institutions, and rising populist politics that frame public health mandates as threats to individual freedom.

In Cameroon, caregivers often demonstrate high willingness to vaccinate, yet fewer than 50% of children age 12 to 23 months were fully immunized as of 2018. Structural barriers such as recurrent stockouts, understaffed clinics, long distances to clinics, and the absence of health workers are some of the challenges with routine immunization. However, this access-driven narrative is further complicated as vaccine hesitancy grows in the region, particularly in the context and aftermath of COVID-19.

Given the dual challenge that Cameroon faces, supply-side constraints that restrict access to routine immunizations and demand-side hesitancy shaped by distrust in government institutions, the country risks facing two distinct but overlapping threats to immunization coverage. If this is not recognized, global immunization goals such as WHO's Immunization Agenda 2030 remain out of reach.