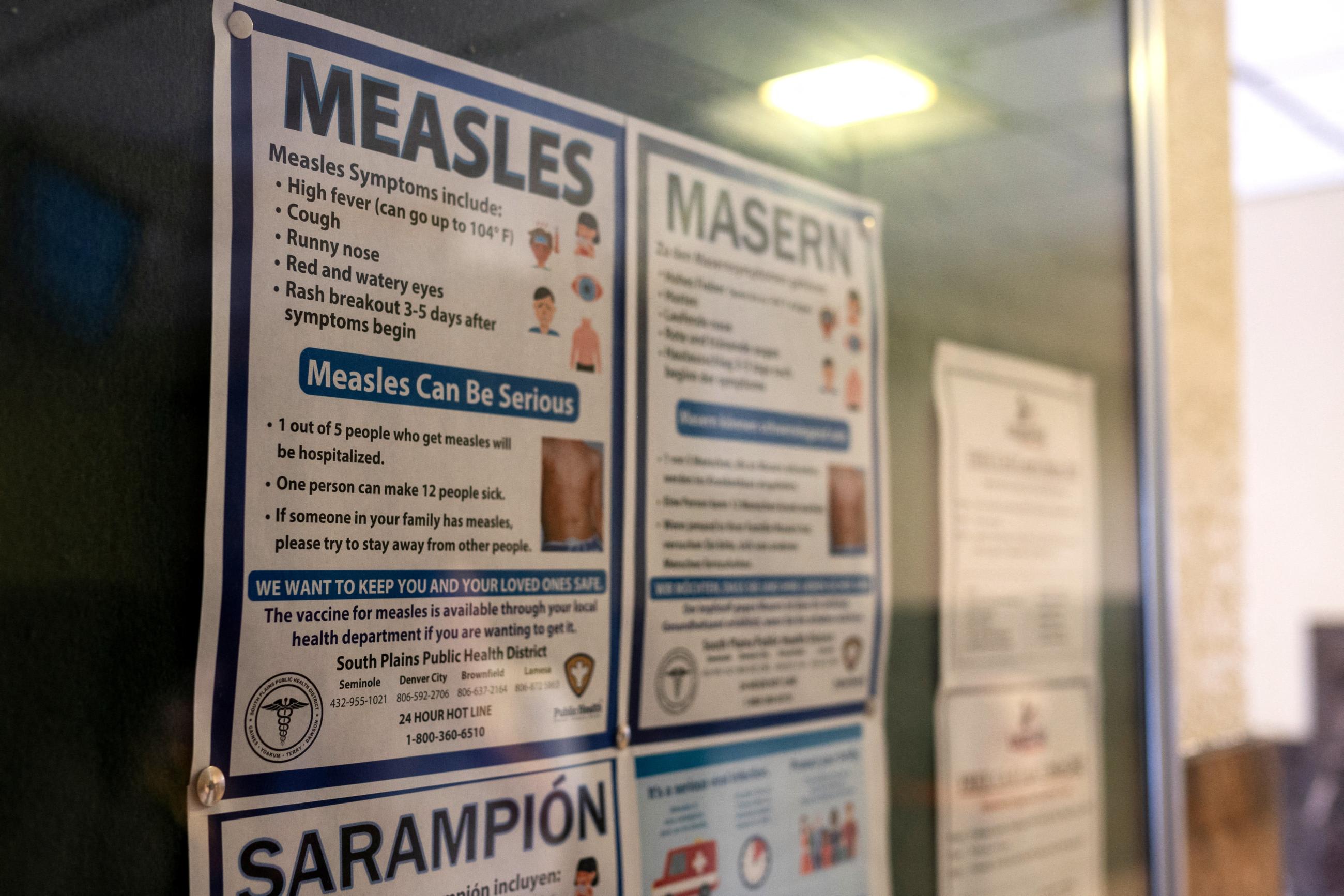

This year's measles outbreak in the United States has, as of April 25, led to 884 cases and three deaths, 30% cases affecting children under the age of 5. The emergency is related to a concerning trend of falling vaccination rates and vaccine doubt: 97% of cases have been unvaccinated or had unknown vaccination status.

The outbreak started in the Southwest United States, a region home to some of the largest populations of American Indian people. Historically, infectious disease has disproportionately affected American Indians, who also have lower vaccination rates than white, non-Hispanic children in the United States.

Think Global Health spoke with John Molina, MD, JD, DHL, of both the Pascua Yaqui Tribe and Yavapai-Apache Nation, director of the Arizona Advisory Council on Indian Health Care, and retired physician with the Indian Health Service and Las Fuentes Health Clinic, about what a worsening outbreak of measles could mean for these communities.

Molina warned that difficulties in accessing health care coupled with feelings of distrust in government-funded facilities and misinformation on social media have left rural American Indian communities vulnerable to large outbreaks as many struggle to receive the preventive health care needed to stave off vaccine preventable diseases.

The interview was lightly edited for clarity.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: West Texas is experiencing a large measles outbreak, which appears to have spilled into New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Many American Indians live in these states. Which populations in your state face the biggest risks from these outbreaks?

Molina: Arizona has 22 fully recognized tribes, and the most susceptible live in rural areas. These areas usually don't have as many services available to them as tribes closer to metropolitan Phoenix do.

Although Native American tribes in general are probably more affected because of their lower vaccination rates, those in the outlying rural areas are at most risk.

Think Global Health: Have Native health-care services mounted an outbreak response? How are they preparing for or handling the outbreak?

Molina: At this point, I haven't heard anything come down from the Indian Health Service (IHS), because Arizona hasn't yet had any identified cases of measles. The IHS is pushing out information to ensure that Native American people within the Indian Health Service systems are up to date on their vaccinations and follow precautions much as they did with COVID-19.

Think Global Health: What is needed to better support American Indian populations as the outbreak worsens?

Molina: Take the experience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Resource assistance for tribes in rural areas is most needed because of geographic challenges that keep those populations from staying up to date on their immunizations. The IHS should take into account what services are available in those rural areas to see whether they can meet the demand.

It can also work to ensure that measles vaccines are available and that a supply chain they can depend on to get vaccines if and when needed is in place.

Think Global Health: American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) children born in 2020 were 20% less likely to be fully immunized by 2 years old (56.7%) than non-Hispanic white children (70.9%). What could be the cause of this disparity?

Molina: The disparity has strongly existed over time. I'm a retired physician and administrator who worked with Indian Health Service for about 30 years. What I find overall, at least in Arizona, is that geography is the biggest problem. Many tribal nations lie in rural areas where accessibility to health-care services is minimal. The other thing is transportation: Many of these areas have rural roads that are difficult to travel.

Further, the Indian Health Service is seriously underfunded, which brings up questions such as whether it has the available services and staff needed to provide vaccinations.

Think Global Health: Have you observed any recent changes in vaccination trends among American Indian populations? Is coverage improving or worsening?

Molina: Essentially over 30 years, vaccination rates have not reached the federal goal of an at least 95% vaccination rate for measles. Places in Indian country are lucky when the rate hits 70%.

One interesting exception came during the COVID pandemic. One tribe, the Navajo (or Diné), had one of the highest vaccination rates in the country, more than 50%. The only way I can explain it is the heavy burden on the community.

When our Indian people begin to see the impact that viral diseases, bacterial diseases, or pandemics have on their communities is when they step out and increase vaccination efforts. The loss of families and of being able to participate in ceremonies that are critical for Indian people had a large impact. We're a community based on kinship and looking forward to future generations. That's what I think caused the increase in COVID-19 vaccination rates.

But I'm also not going to make the supposition that it takes a pandemic to get our people to get vaccinated, but this kind of experience shows that when indigenous communities are hit with a pandemic or a disease that is affecting their family, friends, and future generations is when we see a spike in vaccinations.

Think Global Health: How would you describe the level of trust American Indians have in vaccinations?

Molina: The history of colonization and how government health services negatively affected American Indian people, bring down the level of trust for anything that is government funded.

This feeling goes back to studies done on Indigenous people without their consent. For example, in the 1970s, Native American women were being sterilized without their consent. When this happens in Indian country, it really reduces the level of trust. It also pushes the Indian people to seek out government health-care services only when they're really sick, but not for preventive health care such as vaccinations.

Historically, Indigenous peoples have always relied on traditional practices to take care of any type of illness or disease a person might have, and because of that Indigenous healers are more trusted, sometimes more than doctors. Over the years, I've also discovered that many times Indigenous people will turn to their leaders, such as the tribal council, tribal chairman, or a tribal president, for guidance as to what to what they should do.

On the other hand, I've also noticed that when events occur, such as the pandemic or a potential measles outbreak, American Indian people do have some trust in health-care facilities, but mostly when they have a relationship with the doctors.

Indigenous people who can develop a trusted relationship with their provider are more likely to comply with preventive care or treatment. They have a tendency to create relationships with others but not so much with systems. That's why I've always advocated that health-care systems should really work with providers and medical staff to develop trust with the community they serve.

Finally, social media influences participation in vaccinations. What people see and hear in the media, unfortunately, is often bad information.

Think Global Health: In 2024, only 40% of Americans described childhood vaccines as extremely important. In 2019, 58% did. How would you describe American Indian sentiments toward childhood vaccinations? Are they similar or different to the general trend across the United States?

Molina: Per Indian Health Service records, in 2004 and 2005 vaccination rates were as high as 80% for age-appropriate immunization coverage for 3- to 27-month-olds, and since then the trend in vaccinations has declined. Since 2021, it has barely hit 60% [PDF].

How do we explain this? One trend in public health is when a certain type of illness goes away, people stop paying as much attention. In other words, in this case, measles was considered eliminated. I suspect that when people don't see friends and family getting sick or being hospitalized, communities become complacent.

The other explanation is during the last couple of decades on social media a lot of anti-vaxxers have said the vaccines can cause autism and other conditions even though the MMR [measles, mumps, and rubella] vaccine has proven effective and safe.

Then you have politicians alleging the same things. Misinformation on media and the fact that measles was no longer around began to influence American Indian people. Add to that their limited ability to access services, and vaccination rates dropped.

Think Global Health: Can you recommend a survey or organization that tracks these trends?

Molina: I have two good resources, the Arizona Department of Health Services and an indigenous nonprofit organization called the Inter-Tribal Council of Arizona.

Think Global Health: What resources are needed to better support general childhood vaccination efforts among American Indian populations?

Molina: The Indian Health Service system has tribally managed hospitals and clinics, so it's important that it maintains its efforts to promote vaccinations.

When patients visit a clinic or the hospital, they need to see the promotion of vaccinations. Providers, whether they are physicians or mid-levels, also have a big influence on patients once they develop a relationship. Providers need to check medical records to ensure that the immunizations are up to date, and be actively engaged with their patients to ensure that they're vaccinated.