On Monday, the U.S. Congress put forward a bipartisan bill that would appropriate $50 billion in foreign assistance [PDF] this fiscal year, including $9.4 billion for global health. The proposal is a 16% cut relative to last year's foreign aid package, but it suggests that the United States could spend more on health programs in 2026 than experts expected. If passed, the budget provides $300 million for Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, $5.8 billion for HIV/AIDS programs including the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), and $32.5 million for the UN Population Fund.

The bill is welcome news for global health programs after a disorienting year for the foreign aid sector. When President Donald Trump began his second term in January 2025, the United States altered its foreign aid paradigm with abrupt and sweeping cuts, leaving global health organizations scrambling to understand how health programs and recipient countries would adapt to a pivot from the world's largest donor.

After new data became available from terminated U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) awards and non-U.S. donor budgets in July, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) updated their preliminary estimates in November to form a clearer picture of how global health funding has changed. IHME's researchers found that many countries are in funding limbo.

"As we get more information, the cuts are bigger than we expected, not less," said IHME's resource-tracking lead Joe Dieleman.

Recipient nations are making plans to boost funding—either through the bilateral agreements or planned domestic spending—but have little concrete spending to maintain current programs.

Bilateral agreements are a facet of the America First Global Health Strategy. One understated detail in the congressional bill is that, if it is signed, Secretary of State Marco Rubio will have 90 days to deliver "a comprehensive strategy to guide the structured transition of PEPFAR-supported programs to country-led ownership."

IHME's end-of-the-year estimates, as of November 15, found larger cuts to programs in the Middle East and Asia than previously believed, with the largest drops seen in Bangladesh, Uzbekistan, Myanmar, and Pakistan. The programs most commonly affected involved tuberculosis treatment, water and sanitation projects, and food aid.

The analysis found that 97% of Bangladesh's bilateral U.S. funding had been nixed, dropping from nearly $80 million in 2024 to just $2 million in 2025, and making it the country with the largest percentage of its program cut. Overall, African countries were still the hardest-hit in terms of total dollars lost, and HIV/AIDS programs still lost the greatest proportion of their funding.

"In absolute terms, this is a sub-Saharan Africa problem," according to Angela Apeagyei, who monitors domestic health funding for IHME.

As a result of the cuts, care for diseases like HIV/AIDS have been hobbled, particularly in high-burden countries like Uganda and Tanzania. Physicians for Human Rights reported in September that individuals in those countries are skipping or rationing doses of their HIV medication, and health workers are working to keep programs afloat without pay.

"Many projects have been canceled," said Dieleman. "Building the bilateral agreements that will replace them takes time. Even if it's being done as quickly as possible, the expenditure is not happening [immediately]."

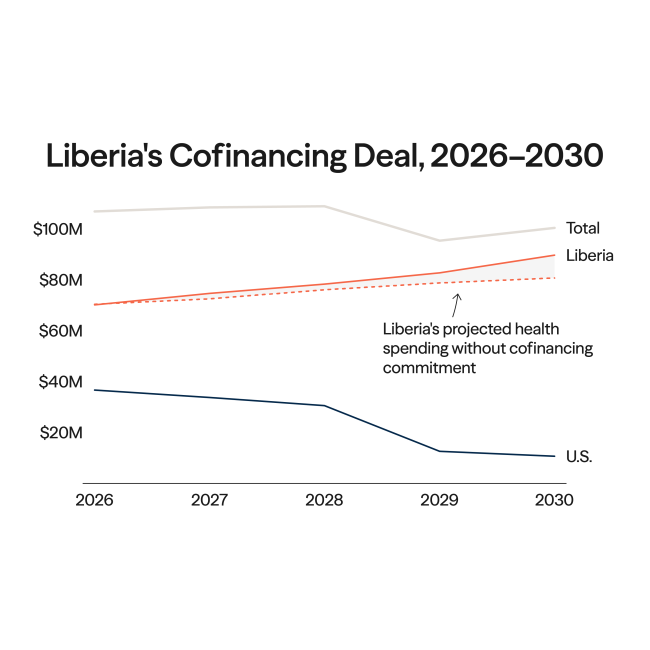

From early December to January 14, as part of the America First Global Health Strategy, the United States entered into 15 bilateral agreements with governments in sub-Saharan Africa. The deals require partner countries to increase their domestic health spending over a five-year period to secure a U.S. funding commitment. According to an analysis by the Center for Global Development, U.S. pledges outlined in the first crop of memoranda of understanding compose just half of the financial support given to those countries in 2024, before Trump returned to office. Funding is also dependent on strict pathogen-sharing requirements for the sake of U.S. pandemic preparedness, which has already led to the suspension of a deal with Kenya over data privacy concerns.

Tanzania, once a major PEPFAR recipient, has yet to strike an agreement with the United States. In December 2025, the U.S. State Department announced that it was reviewing its relationship to the country because of religious repression and "persistent obstacles to U.S. investment." South Africa, which experienced a 78% drop in bilateral health funding from the United States and maintains the world's highest number of people living with HIV, has also not entered an agreement amid increasing geopolitical tensions.

On the country level, governments are assessing how to increase their domestic spending in response to cuts and how to build their health sovereignty.

"There's great enthusiasm in using this moment to reframe health spending in Africa as an investment and center Africa's voice in global health governance," said Apeagyei. "At this point, though, we're in the phase where it's speeches and baby steps. With a little more time, we will see how that translates into concrete steps."

In April, Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) outlined an agenda establishing the goal of enabling at least 20 countries to finance more than half of their health budgets through domestic sources by 2030. IHME's initial analysis found that a few countries, including Ethiopia, have been able to mount meaningful responses, whereas others have been hindered by conflict.

Ethiopia's Ministry of Health has been actively advocating for more health-sector funding according to IHME's country partners, engaging Arab donors and increasing the government's share in a program funding family-planning services. For Niger, aid cuts have hurt the government's ability to provide public services, and military spending has been prioritized because of growing instability.

In 2026 and beyond, IHME predicts other potential responses to include technological innovations to stretch limited resources and greater investment from the private sector. Countries' ability to increase spending will depend heavily on their political and economic contexts. Dieleman noted that budget cycles have only just begun in many African countries, and it remains to be seen which tangible responses take hold.

"Resources aren't being expended," said Dieleman. "That has very real ramifications [for health]."