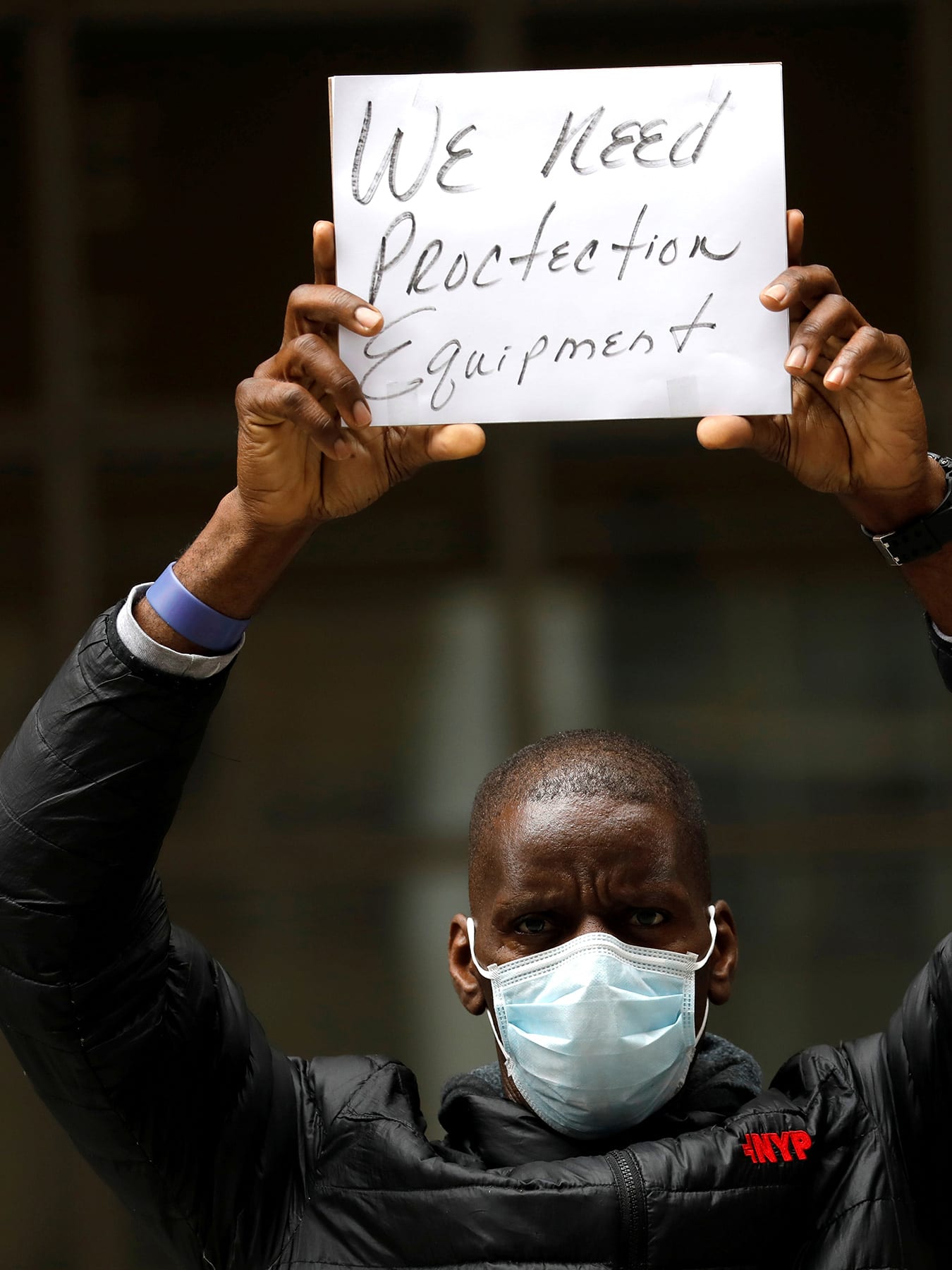

So many shortages of critical medical supplies—including masks, disinfectants, ventilating machines, and medicines—have emerged in the COVID-19 crisis that their supply has almost become an international crisis of public health concern on its own.

A supply-side "Buy American" program won't add either flexibility or redundancy, two key elements necessary for emergency preparedness

In the United States, the alarming shortages have prompted calls for drastic action, such as a "hard decoupling," or cutting trade ties with China. But this focus on a single source country misses the real challenge of preventing supply shocks. Disaster preparedness experts should instead focus on resilience. A supply-side "Buy American" program won't add either flexibility or redundancy, two key elements necessary for emergency preparedness. In fact, hard decoupling might reduce our resilience, as we saw, for example, when refineries were taken out after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Heavy reliance on domestic production left the United States in short supply. Private enterprises will be rethinking the supply chain, but we also need to plan how best to provide government backstops. Both the private and public sectors have to think how to make sure a brilliant late twentieth century innovation in commerce—the just-in-time inventory and production system—does not inhibit the resilience needed for crisis management.

The world is heavily reliant on Chinese personal protective equipment. The reasons for this are simple. Companies seeking the cheapest location for making components and assembling final products were attracted to China initially by low labor costs, and then they stayed even as costs rose. This made these Chinese companies the active producers of personal protective equipment they are today.

Making the future global supply chain more robust can be done in part by diversifying

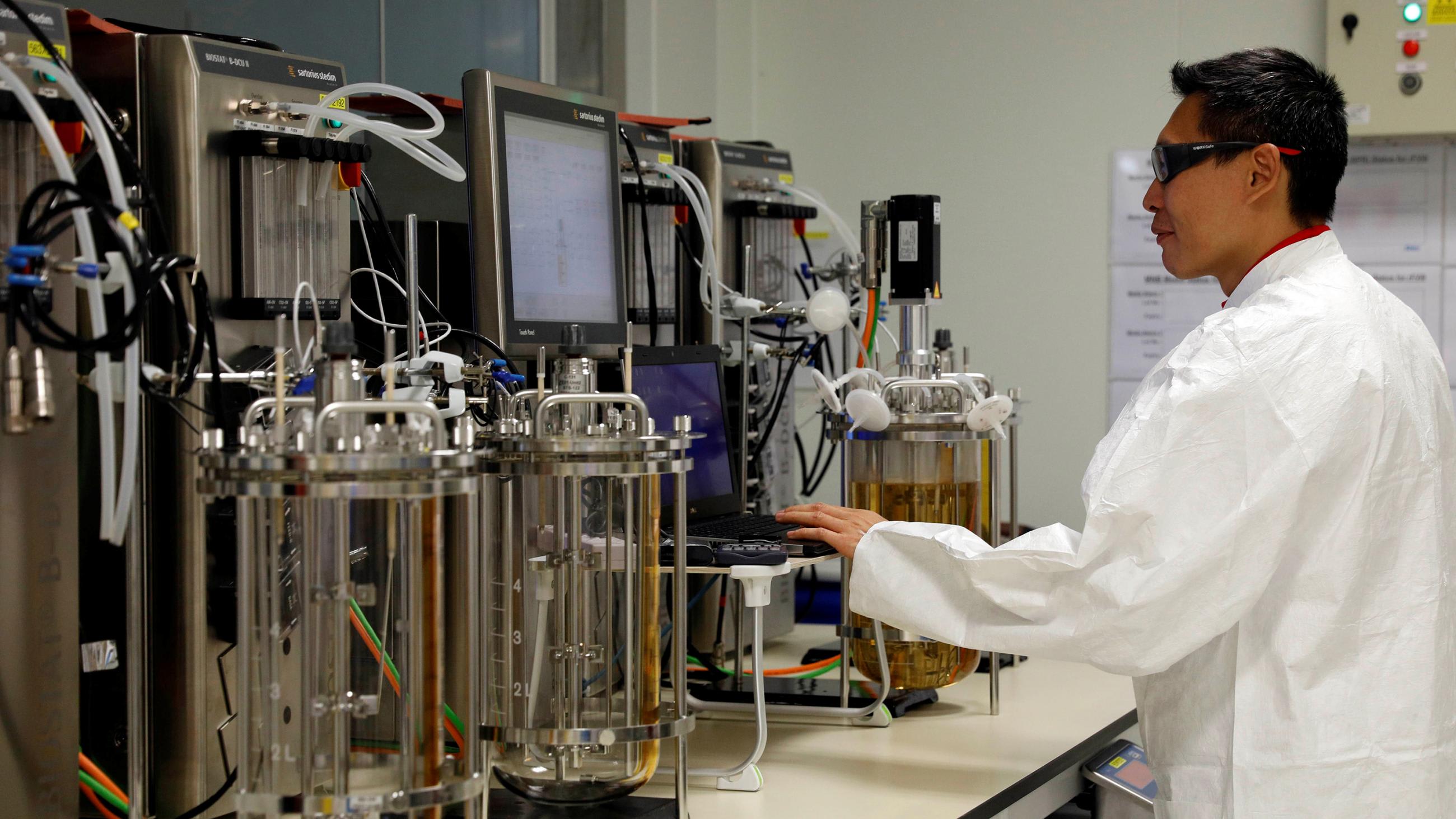

But this story of dependence on imports is also about our dependence on exports. The United States and other advanced economies benefit by exporting our high-quality products and services. To bring production home would be to reduce our high-value-added exports and risk losing domestic income. Fewer exports would make us poorer. As we've seen, our current global supply chain is not well-cushioned for risk. This time it is a pandemic, but other disasters are looming—such as those resulting from climate change. Making the future global supply chain more robust can be done in part by diversifying. In the wake of COVID-19 we expect to see many companies staying in China but looking to add additional sources: places like Vietnam, where costs are lower than they are in China, or Mexico, where there is the advantage of the 2018 United States-Mexico-Canada trade agreement, often referred to as NAFTA 2.0.

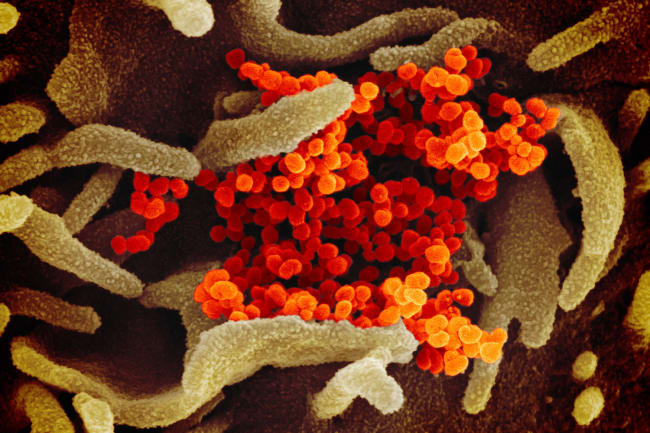

But fixing resilience in our supply chains gets us only part of the way toward real resilience. The larger issue is our reliance on "just-in-time" production—a manufacturing approach whereby companies make only the amount needed by their purchaser in that day or two. This saves resources otherwise tied up in inventory. Whether retail or manufacturing, enterprises no longer have large warehouses, but order on demand. Even hospitals only order the pills, masks, and ventilators they expect to use in a very short period. They manage, through the careful scheduling of the elective surgeries on which their income depends, to ensure that their beds are kept at least at almost full capacity almost all the time.

This is true in both private for-profit hospitals as well as nonprofit health systems in the United States. It's also true in places that have nationalized health system, like the United Kingdom.

Just-in-time is a brilliantly efficient idea, derived from the Japanese production methods, and it saves organizations money by allowing more efficiency in warehousing and by revealing errors more quickly during smaller production runs.

But in a crisis, just-in-time fails us, as it is failing us now. Suddenly with COVID-19, we need capacity, not inventory efficiency. We just don't have enough of many of the things we need. The solution, though, will not come from bringing production home, because just-in-time is so cost effective it will continue to dominate bottom-line conscious organizations regardless of where they source from. We could move our entire medical supply production stateside and hospitals would still not have enough on hand. We cannot stop just-in-time—nor should we. We need to think beyond efficiency itself. We should consider otherwise inefficient but secure methods like building a robust stockpile, just like we have a Strategic Petroleum Reserve to provide oil to our military and our society at large in case of emergency.

We need to think beyond efficiency itself

In theory we have a national medical stockpile, a strategic health reserve, as well, but we've discovered that it isn't nearly as effective as our oil stockpile. For one thing, its contents are a government secret, as opposed to the open accounting on the Strategic Petroleum Reserve's website. The medical stockpile began as a simple storehouse for vaccines to protect against potential bioweapons, and it has never been fully converted into an openly managed resource for the states to use during emergencies. Without scrutiny, materiel was left to expire. We need a program that involves constant rotation of material before it expires, similar to the way Singapore planned for its National Centre for Infectious Diseases to be open all the time and used, but with most of its capacity in reserve to deal with epidemics and pandemics.

This problem created by just-in-time manufacturing and service provision is not going to be solved either by the free market or by budget-cutting service provision bureaucracies.

The secret to resilience is redundancy. We can build it not by rejecting all the economic benefits of globally integrated markets, but by ensuring the private sector diversifies its sourcing and requiring an active government effort to ensure against supply shocks. With economies in free fall and human deaths tragically mounting every day, benefiting from a supply chain with built-in redundancy seems hardly redundant at all.