On January 5, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) changed the country's childhood vaccine schedule to cover 11 diseases instead of 17, no longer recommending routine protections for flu, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, meningitis, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and rotavirus. The new schedule more closely resembles Denmark's, despite broad differences in the two countries' populations and health systems.

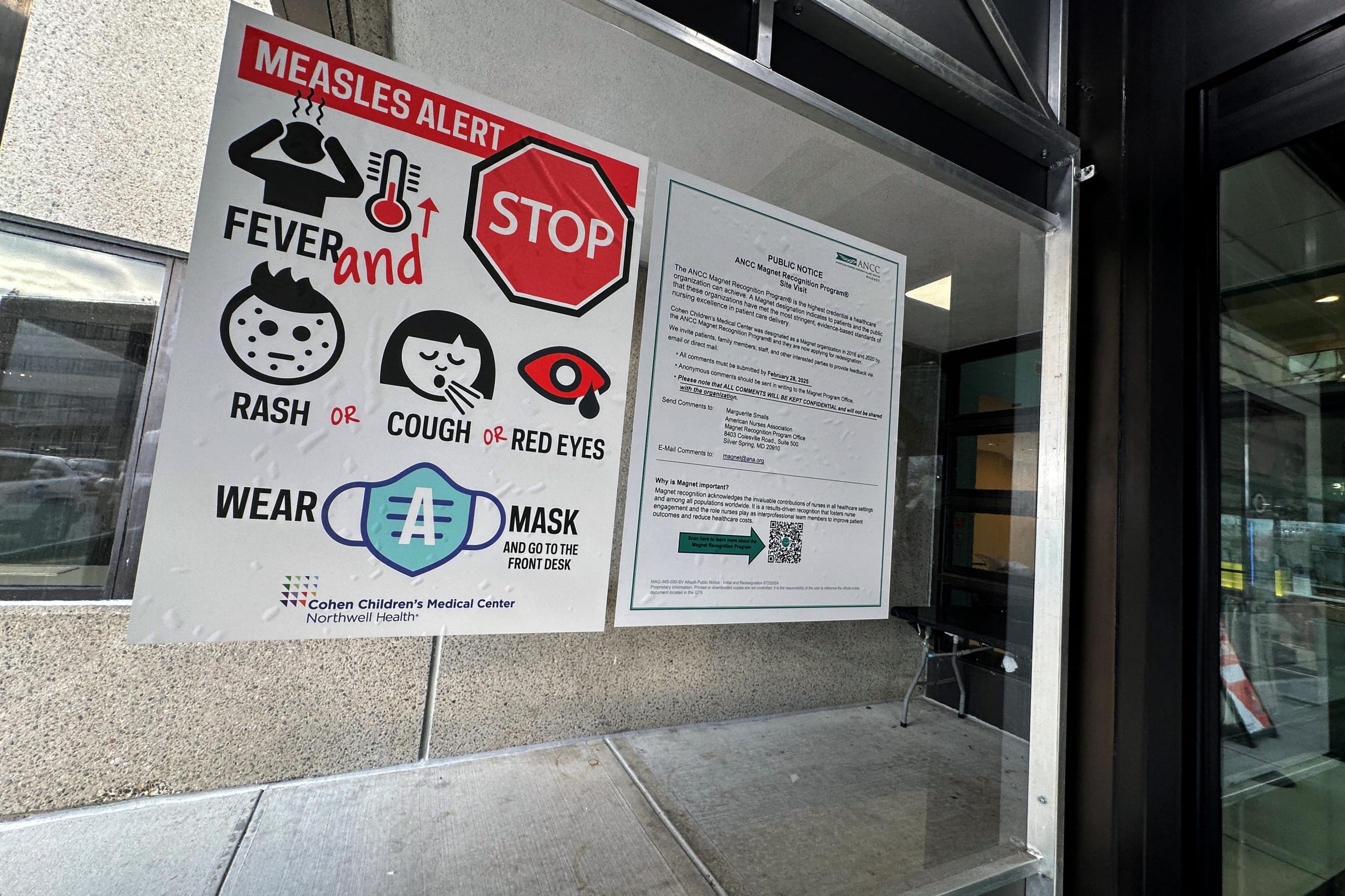

The decision, now being challenged in court by medical groups including the American Academy of Pediatrics, comes as dropping vaccination rates and growing nonmedical exemptions have allowed preventable diseases such as measles to tear through communities in the United States. According to Think Global Health's vaccine-preventable disease tracker, the country's largest outbreak is now centered in South Carolina, where 646 cases have been recorded as of January 20, 2026, and 563 involve unvaccinated residents. South Carolina has reported 499 new cases since mid-December.

The United States is also facing a severe flu season, fueling the highest weekly hospitalization rate from flu in children under 18 since 2010. This season has seen 32 children die from flu, 90% of whom were unvaccinated and 15 of whom were reported in the last week. This winter, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is also elevated across the country, and emergency department visits are rising among infants.

To learn more about how the U.S. retreat on vaccination will shape local and global outbreaks, Think Global Health spoke with Seth Berkley, the former head of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Gavi is a public–private partnership dedicated to vaccinating children in low-income countries, and Berkley is a physician and infectious disease epidemiologist who co-led efforts to equitably distribute vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic via the COVAX initiative. His new book, Fair Doses, explores how Berkley and his team navigated growing vaccine skepticism, intentional disinformation, and nationalism to confront COVID-19, and concludes that we are less prepared for a pandemic now than we were then.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: What was your reaction to the recent decision to change the U.S. vaccine schedule, and which change concerns you the most?

Seth Berkley: This was the biggest change in vaccine policy that has occurred without any new data in any country's history. In the past, if we had a problem with a particular vaccine, it might have been withdrawn—but nothing like this. It's a real tragedy, and children will die because of it.

All of the changes concern me for different reasons, but the one that was shocking was hepatitis B. In the old days, if a person got hepatitis B, they usually got it around the perinatal period and then they'd get a chronic infection. That chronic infection allows the virus to dramatically affect the person over their lifetime, and it increases the incidence of liver cancer and liver disease.

The challenge is that we're comparing ourselves to a place like Denmark which doesn't require hepatitis B. Denmark is a small country with universal health coverage and universal follow-up. They've got health insurance and a fairly homogeneous population.

The safety profile of that vaccine has been extraordinary

The United States doesn't really have a health system. Many people sit outside of it, and they don't get the follow-up they need. If you stop mandatory vaccination in infancy, you will end up with children who will get infected and who will go on to develop liver cancer. That's just an unnecessary thing.

The safety profile of that vaccine has been extraordinary. I know the vaccine well because I was in one of the original trials as a physician at the beginning, so I've had special interest in it and followed it over time. Nobody's ever claimed any challenging side effects or problems. But here we are. The [United States] just decided to stop it for no apparent reason.

TGH: We're in the midst of a particularly bad flu season. Could we expect to see more seasons like it if the new schedule convinces more parents not to vaccinate their children against the flu?

Seth Berkley: Flu is an unusual agent. We've known flu forever, and vaccines have been out for a long time. We choose a flu vaccine by looking at what was in the Southern Hemisphere, based on the idea that it would be likely to spread into the Northern Hemisphere. Sometimes it does, but sometimes it doesn't.

The question on flu is: How well matched is the vaccine to the strains that are circulating? Some years you get a vaccine that's 50% to 60% efficacious, and some years it's 30% or 40%. There are amazing new technologies that allow you to make vaccines faster, that allow you to better predict what the strains will be and to create vaccines that are more effective. But a lot of that science is also being suppressed now. The recommendation is always to take the flu vaccine. One, because you can get some protection. Two, it may protect against severe disease, even if it doesn't protect against mild disease. And three, if you keep taking those vaccines every year, you begin to build some broader immunity to protect you against strains in the future.

It's not clear to me how this will change in the United States, but my view as a vaccine specialist is that we should be using the best technologies to make better flu vaccines to reduce deaths—and there are a lot of deaths from flu, an estimated 290,000 to 650,000 deaths a year globally. Particularly during a year like this, there's also a lot of misery and morbidity.

Same thing goes for COVID and RSV. RSV is the largest cause of children's hospitalization from infectious diseases, and those numbers were on their way down with the relatively new vaccine. If these vaccines are not used, death rates will stay high.

TGH: We're already seeing the consequences of lower vaccination rates in the current record-setting measles outbreaks. Why should people care about measles?

Seth Berkley: That's an excellent question. In 2000, there were an estimated 760,000 deaths from measles worldwide. In 2024, that number was brought down to 95,000, but measles is still a disease that kills a lot of people.

When I was working in Sudan, there was a terrible measles outbreak in a community. Every day, I would wake up and count the new little baby graves there. Talk about something that is a dramatic reminder of what this can do.

Measles kills people in a few different ways. It can kill acutely, through respiratory disease, but there's another disease called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) that is horrible. Basically, years after the initial infection, your brain liquefies and there's nothing you can do. It doesn't matter how sophisticated your care is.

Roald Dahl, the author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, had a daughter who had an acute version of that happen to her. He wrote an open letter about her, saying that he would do anything to bring his daughter back and that everyone should get the measles vaccine.

There's a third thing that most people don't discuss: in a child who's developed some immunity and has had other vaccinations, measles can reset their immune system. They get "immune amnesia" and become susceptible to many other infections. Some of the deaths that occur from measles happen later from other causes because their immune systems have this amnesia.

Measles is probably the disease I'd worry about the most if we were to stop vaccination. So far, the United States hasn't. At the beginning of this, when the first child died in Texas, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. went out and said to take vitamin A and cod liver oil. Finally, people pushed him, and he said to take vaccines.

I hope they don't move to take the measles vaccine away. President Donald Trump threatened to. In all caps, he put out a statement that no child should get the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) combined vaccine, they should only get M and M and R separately. The first problem is that then producers would need to make six doses, to give across two sittings during childhood, instead of two doses. Second, those three vaccines are not available separately in the United States like they are in other countries.

TGH: How equipped are low- and middle-income countries right now to prevent outbreaks like measles? What does this mean for pandemic preparedness?

Seth Berkley: Coming out of the worst pandemic in 100 years, there are a lot of lessons to be learned. One reason I wrote Fair Doses was to talk about those lessons. You'd expect countries to be better prepared, and certainly there was movement toward that. However, after the United States pulling out of the World Health Organization and reducing development aid—including closing the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)—the world is not prepared. It's much less prepared than it was even before COVID, in terms of vaccinations.

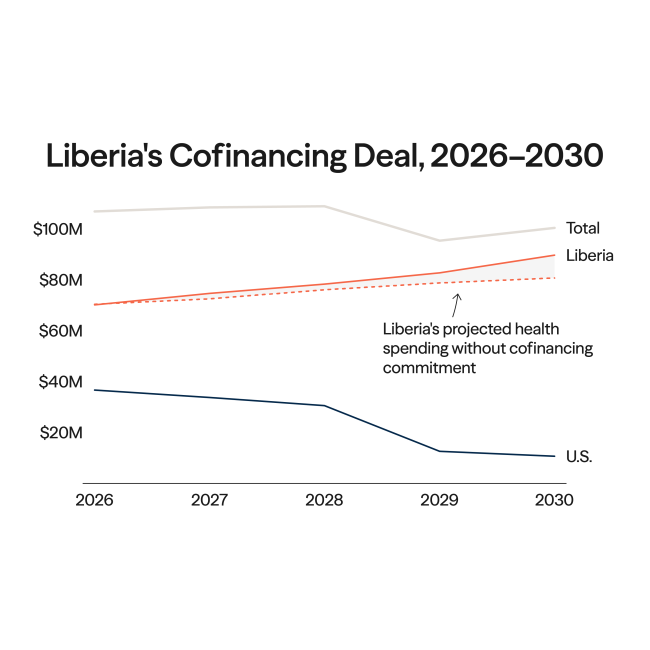

For the first time, Gavi didn't make its funding goal, in part because the United States decided to not provide any funding to Gavi. That was a tragedy because Gavi was supported by the United States: even during President Trump's last administration, when the alliance received a 5.5% increase in U.S. funding. Gavi was the only global health initiative that received an increase during that period from him.

As a result of withdrawing that money, we estimate that 75 million fewer children will be immunized, and that's likely to lead to 1.2 million additional deaths. This is a real challenge. Gavi is the main funder of immunization in the developing world, but countries that also have their budgets slashed because of reduced aid from USAID and other donors means there'll be less money to invest in health as well. We're likely to see increased infections and outbreaks.

The other thing that's happened is that the systems established to detect outbreaks—the most important being the primary health care system and the immunization delivery system—have broken down. Immunization is the most widely distributed health intervention in the world: About 90% to 91% of households get at least one contact with the routine immunization system, and that's higher than anything else. Health workers are prepared to identify outbreaks and notify the authorities.

TGH: What else should readers know?

Seth Berkley: For every dollar invested in vaccines, you get about a $21 return. If you account for the benefits of being healthy and preventing diseases, that figure rises—for every dollar invested—to a $54 return. There's nothing like that in health.

We're in an era of poly-epidemics. We're going to have an acceleration—given population is still rising, given the density of urban environments, given the refugee crises, given climate change—and we're going to have more outbreaks. Prevention makes sense not only for public health but also for global safety and economics.

We spent $14 trillion on COVID. We should have learned our lesson. Maybe we want to do a better job next time?

EDITOR'S NOTE: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.