The past several decades have seen an alarming spike in communicable disease outbreaks worldwide. Given a confluence of host, virologic, environmental, and human factors, experts agree that the next pandemic could already be on the horizon.

In a globalized world, changes in how people use land and interact with their ecosystems—such as rapid deforestation and agricultural expansion—have resulted in humans and animals coming into more frequent and intense contact with one another, increasing opportunities for what is known as "zoonotic disease spillover."

Spillover occurs when a pathogen is transmitted from one species to another, such as a vertebrate animal to a human. In the past few years alone, numerous disease outbreaks have had suspected or confirmed zoonotic origin, including mpox (formerly known as monkeypox), Ebola virus disease, dengue fever, and COVID-19. Experts also recognize the need to prepare for another possible Disease X, a term used to describe a currently unknown pathogen with pandemic potential.

To direct resources toward the most high-consequence pathogens, it is paramount that leaders have an accurate concept of pandemic risk—for individual viruses as well as viral families. Several institutions are developing disease rankings at national and global levels, including the Priority Zoonotic Diseases Lists facilitated by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Research and Development (R&D) Blueprint created by the World Health Organization.

It is paramount that leaders have an accurate concept of pandemic risk

Although important for informing global and national health priorities, disease-ranking initiatives are time intensive and costly processes, requiring ongoing updates as new data and pathogen discoveries emerge. To complement these efforts, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) has partnered with the University of California, Davis, to expand SpillOver, their viral risk ranking platform launched in 2021.

Developing the SpillOvers Application

The original SpillOver risk ranking framework (SpillOver 1.0), an open-source webtool launched by researchers at the University of California, Davis One Health Institute, estimated the relative spillover potential of wildlife-origin viruses to humans based on a series of host, viral, and environmental risk factors determined via expert opinion and scientific evidence.

SpillOver 1.0

UC Davis's first iteration of its risk ranking tool shows the top 12 viruses most likely to infect humans, all of which are zoonotic

Its next iteration, SpillOvers 2.0, has rebranded to better describe the diversity and frequency of virus spillovers to people. The new platform uses a One Health approach, which recognizes the interdependence of human, animal, and environmental health. It will expand to include domestic animal and vector-borne viruses and assess pandemic risk rather than just spillover risk for wildlife viruses.

Through a series of focal interviews and breakout discussions at a workshop convened in October 2023, the SpillOvers team identified and consolidated 68 unique environmental, host, and viral risk factors for pandemic potential. Through additional expert surveys, this list of risk factors will be further refined, ranked for prioritization, and assigned weights, such that new risk scores can be calculated for each virus in the SpillOvers 2.0 database.

Using natural language processing techniques, the team at UC Davis also aims to collect risk factor data from an array of publicly available sources, including biomedical databases and peer-reviewed literature, to create the most up-to-date and comprehensive database of candidate viruses for Disease X.

The SpillOvers team identified and consolidated 68 unique environmental, host, and viral risk factors for pandemic potential

By incorporating data science tools with mixed-methods research, the application will allow for a dynamic and prospective exploration of the pandemic risk posed by zoonotic viruses, helping stakeholders at national, regional, and global levels to better anticipate and prepare for epidemic and pandemic threats. Researchers will set up automated data pipelines for the long-term sustainability of the project.

"The time of simply hoping that we will be able to effectively and equitably respond to the next health crisis using only the knowledge gained during the last major health emergency has passed," says Jonna Mazet, vice provost at Grand Challenges, University of California, Davis. "One hundred years after the 1918 influenza pandemic, we weren't much better prepared for the COVID-19 catastrophe because we didn't anticipate and make provisions for a novel pathogen."

CEPI's 100 Days Mission

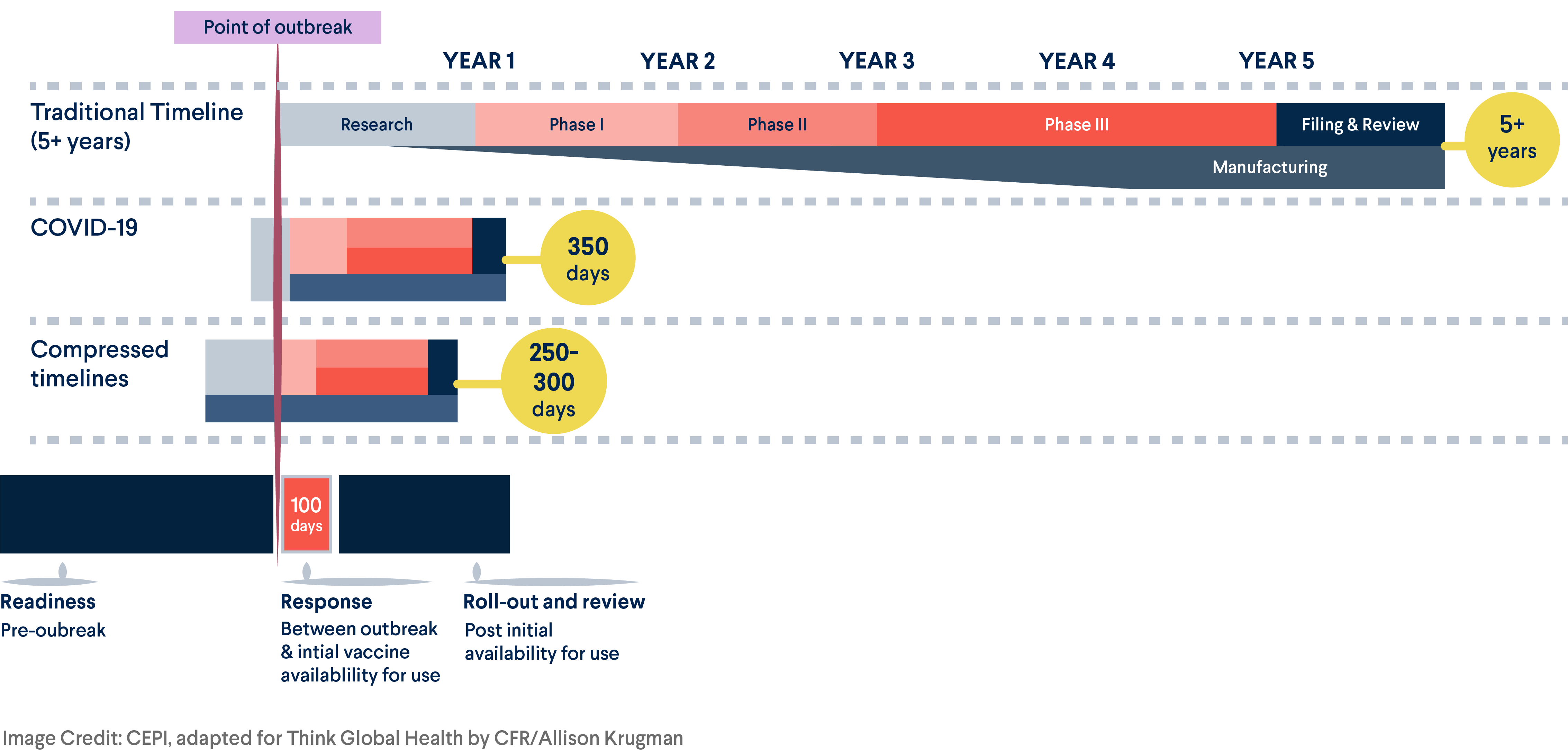

The devastating consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the need to quickly deliver safe and effective countermeasures such as vaccines during a public health emergency. However, the timeline for vaccine development has historically been lengthy, often taking years or decades to complete clinical trial phases and regulatory approvals before manufacturing and distributing doses.

To ensure that the world is as prepared as possible to rapidly and equitably make vaccines available during the next pandemic, CEPI also developed a vaccine library targeting high priority viral families and related prototypical pathogens, speeding up the process of vaccine discovery and development to within 100 days of identification of a novel pathogen, or Disease X. Toward this 100 Days Mission, CEPI will prioritize efforts to establish a vaccine library based on the risk ranking of viral families provided by the SpillOvers team and resulting application.

Reducing the Vaccine Development Timeline

To achieve CEPI's 100 Days Mission, vaccine development will require a paradigm shift

"The response to COVID-19 demonstrated scientific advances that have allowed the world to start talking realistically about compressing vaccine development responses to 100 days—a plan CEPI calls the 100 Days Mission," says In-Kyu Yoon, acting executive director of Vaccine R&D at CEPI. "The data gathered through the SpillOvers program will allow CEPI and researchers around the world to align and prioritize R&D investments and help the world to stop the next pandemic before it starts."

Ultimately, through sustained engagement with the global community and automated data input, the project aims to improve both the risk ranking tool and the world's collective understanding of the risks posed by different viruses and virus families.

"We must anticipate and prepare for Disease X in a data-informed manner, and I believe that SpillOver and CEPI's 100 Days Mission are the best first steps toward health security for all," Mazet says.