Yellow fever is surging across the Amazon basin. From January to August 2025, health officials from Central and South America confirmed 270 human cases and 108 deaths—a 65-fold increase over the same period in 2024. Exacerbated by climate change, deforestation, shrinking vaccine coverage, and a more mobile population, the resurgence of this mosquito-borne disease coincides with the thirtieth United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30), in Belém, Brazil.

COP30 offers a pivotal opportunity for leaders to address the intersection of climate change and health, nowhere more urgently than in the fight against yellow fever and other climate-sensitive diseases. The Belém Health Action Plan [PDF], developed by Brazil's health ministry and the World Health Organization (WHO), proposes building climate-resilient health systems and prioritizing infectious disease prevention. But beyond rhetoric and to fully deliver on its promise, the plan must include yellow fever. Integrating health into the plans at the heart of the Paris Agreement—nationally determined contributions (NDCs)—and unlocking climate finance for immunization campaigns and surveillance could curb a resurging threat and protect millions from future climate-driven epidemics.

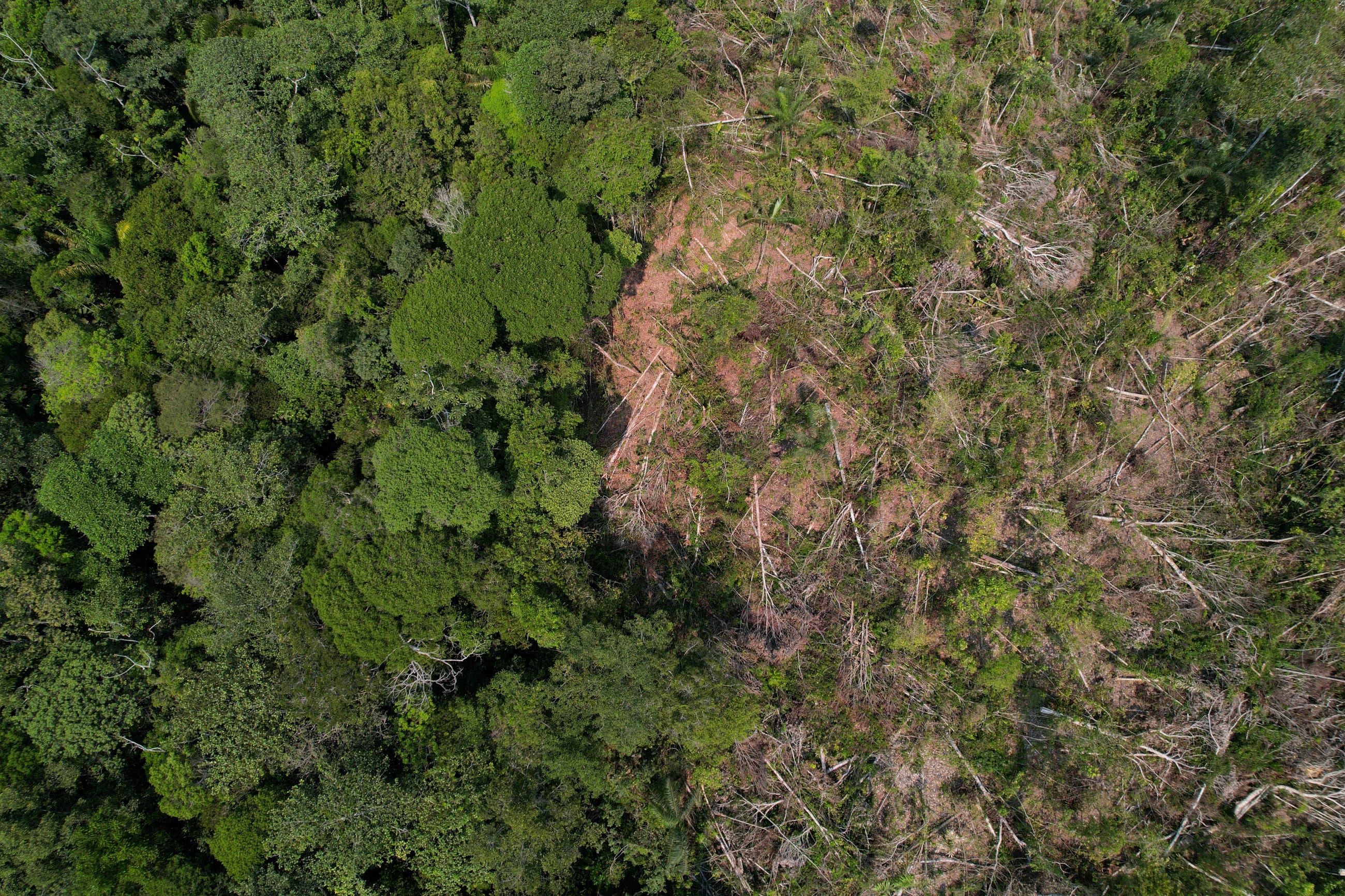

As leaders gather in the heart of the Amazon, home to one of the world's largest carbon sinks, they will find themselves in a hotspot for disease emergence. Policymakers can either confront yellow fever and the health consequences of ecological collapse or continue to treat climate and disease as separate crises. The price of inaction will be measured in lives lost, livelihoods disrupted, and communities destabilized.

A Perfect Storm in the Amazon Basin

On March 26, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) issued an epidemiological alert [PDF] over a surge in yellow fever cases across the Americas. The first quarter of 2025 alone saw 131 cases and 53 deaths, more than double the 2024 total. Brazil and Colombia have reported infections in areas where city expansion meets rural and forested zones, such as São Paulo and Tolima—regions traditionally outside the yellow fever risk zone. This encroachment raises the risk of the virus reestablishing its urban transmission cycle through mosquitoes, something not seen in more than 70 years.

Deforestation and climate change accelerate and expand the virus's spread

Yellow fever, caused by a Flavivirus and transmitted by mosquitoes such as Aedes aegypti and Haemagogus, circulates in a sylvatic (jungle) cycle where the blood-sucking bugs living in forest canopies bite monkeys who carry the virus. The mosquitoes then spread the virus to other monkeys and potentially to humans. Although this cycle—and the virus—are normally confined to forests such as the Amazon, the pathogen becomes a threat to humans when it spreads into urban areas, typically from infected travelers moving through forested areas.

Symptoms range from high fever, muscle pain, and nausea in the early stages to a secondary toxic phase characterized by liver failure, jaundice, and bleeding. In severe cases, death occurs in 30% to 50% of patients. Without antiviral treatment, patient survival depends on supportive care and hydration—something that is rarely accessible in rural Amazonian communities.

Deforestation and climate change accelerate and expand the virus's spread. The clearing of forests in the Amazon reduces canopy cover, fragments ecosystems, and forces wildlife—such as monkeys and mosquitoes—into closer contact with human settlements. These land-use activities increase the risk of yellow fever virus spillover from animals to people. Studies show that high forest edge densities and intermediate forest cover significantly increase yellow fever events among humans and nonhuman primates.

Research on landscape structure in São Paulo likewise finds that forest-urban edges lower ecological resistance and accelerate viral spread. Recent reviews of mosquito-borne viruses in the Amazon highlight how deforestation, land-use change, and fragmented vegetation near settlements increase contact between sylvatic cycles and human populations. Entomological surveys in Brazil further show that mosquito abundance is highest near forest fragments, underscoring the risks at these interfaces.

Although direct evidence is limited for specific interventions, established vector-control measures—such as eliminating breeding sites, improving drainage, waste management, and maintaining green belts—remain critical components of urban resilience strategies that integrate disease prevention by design.

Rising temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns expand the range of mosquitoes and speed up their reproductive cycles. A 2024 study projects that South America's yellow fever and dengue risk zone could grow 7% by 2050 due to warming and changing precipitation. Another study found that droughts in the Amazon are driving primates and mosquitoes into human-populated areas in search of water, dramatically increasing contact rates.

This geographic convergence increases the chances that populations already battling dengue or Zika could also face renewed outbreaks of yellow fever.

Prevention Starts Before the First Case

Prevention remains the best defense against yellow fever. The EYE Strategy (Eliminate Yellow Fever Epidemics), launched in 2017 by the WHO, UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund), and Gavi, seeks to protect 1 billion people—mostly in Africa and the Americas—through stronger surveillance as well as mass and routine vaccination. Yet midterm evaluations from the WHO warn that uneven coverage, limited surveillance, and funding gaps threaten progress. Although Gavi has committed more than $400 million for vaccination through 2025, diagnostic efforts received just $8 million between 2019 and 2022, creating major delays in outbreak confirmation. National budgets often deprioritize yellow fever, leaving dangerous gaps in preparedness.

Through the Belém Health Action Plan (BHAP)—a strategic initiative within COP30's Action Agenda—Brazil aims to strengthen public health systems, advance equity, and promote climate justice. The initiative signals a broader recognition of the link between protecting ecosystems and preventing disease. It also calls for increased climate funding to boost vaccine production, epidemic surveillance, and rapid-response capacity across low- and middle-income countries.

The 17D vaccine for yellow fever, developed in the 1930s, provides lifelong immunity with a single dose in more than 95% of recipients. Yet vaccination coverage remains dangerously low. In Brazil, less than 75% of the population is immunized—far below the 95% threshold needed to prevent outbreaks. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted routine immunization, strained public health resources, and worsened hesitancy. At the same time, vaccine production remains limited to a handful of manufacturers and still relies on slow, egg-based techniques.

COP30 delegates now have an opportunity to turn plans into action—particularly by supporting scalable vaccine production technologies such as germ-free egg and cell-culture platforms. These advances could enable countries to build regional vaccine stockpiles, improve health resilience, and respond more quickly as climate-driven outbreaks become more frequent. In doing so, they would fulfill Objective 16 of the COP30 Action Agenda: making health systems more adaptive, prepared, and regionally responsive.

Across Latin America, creative local approaches are showing what climate-adapted prevention looks like in practice. In Colombia, outreach teams are using empathy-based communication and motivational interviewing to reduce vaccine hesitancy. In Peru, PAHO and local health authorities have developed intercultural health initiatives to reach Indigenous populations, including outreach efforts that adapt health materials to cultural contexts. In some regions, those efforts complement or substitute for traditional fixed health services. These approaches embody the inclusive, community-driven strategies that climate-health policy aims to scale—strengthening resilience from the ground up.

In Brazil, federal authorities and conservation agencies have run joint campaigns urging people to protect primates—key hosts in the yellow fever jungle cycle—explicitly tying prevention and conservation messaging to vaccination and early warning. Partnerships between nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), universities, and research institutes—including the Golden Lion Tamarin Association, Fiocruz Bio-Manguinhos, UENF, and ICMBio—led to the first vaccination of endangered golden lion tamarins in the Atlantic Forest, a milestone that joined wildlife protection with disease prevention. At the same time, forecasting models and locally led monitoring efforts are helping Brazil anticipate outbreaks and respond faster. These efforts demonstrate how environmental data and community knowledge can work together to prevent disease before it spreads.

By bridging health, conservation, and climate, these interdisciplinary strategies offer a model for the Belém Health Action Plan to build on. Delegates can incorporate them into NDCs, secure climate financing for vaccination and surveillance, and accelerate innovation in vaccine production to strengthen regional preparedness.

Tech, Data, and Diplomacy: Strengthening Regional Health Resilience

Innovation is also transforming how scientists detect and contain outbreaks. In 2024, Brazil unveiled a new diagnostic test that can reliably detect the yellow fever virus in nonhuman primates within approximately 40 minutes. It functions like a portable lab, using a simple heating process rather than complex machines, making it faster and easier to use in the field. Although the pilot focused on monkeys, testing materials were designed with human-circulating strains in mind. Such tools could enable earlier detection of virus circulation in wildlife, improving the chances of acting before human outbreaks escalate. This kind of diagnostic advance directly supports Brazil's climate-health priorities by strengthening early warning at the forest frontier.

Together, advances in portable diagnostics, predictive modeling, and cross-border cooperation are shaping a new model for regional health resilience

Technology is also reshaping preparedness through environmental forecasting. Brazilian research teams have developed predictive models that use meteorological, ecohydrological, and historical yellow fever data to forecast outbreaks weeks in advance and identify high-risk municipalities long before cases appear. Although most models project up to three months ahead, they demonstrate how investment in data infrastructure can strengthen early warning networks across the region. These tools reflect the BHAP's call for climate-informed surveillance and exemplify how integrated data strategies can help deliver on COP30's vision of resilient health systems.

Additionally, regional collaboration is advancing. Countries sharing the Amazon basin have already begun coordinating health responses across borders. In 2025, in Brazil's Roraima region, mobile health units are working to reach transient populations along both sides of the border. In Colombia's Putumayo region, health teams worked with Brazil's Ministry of Health and PAHO to strengthen yellow fever surveillance, including primate and vector monitoring. Community-based surveillance models pioneered in Colombia are now being shared with Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Paraguay under the PROTECT project, and Fiocruz Amazônia and partners are piloting the INSIGHT initiative in the Triple Frontier of Brazil, Peru, and Colombia to build joint surveillance capacity.

Together, advances in portable diagnostics, predictive modeling, and cross-border cooperation are shaping a new model for regional health resilience. As COP30 unfolds, investing in these tools could transform early detection into one of the Amazon's strongest shields against future epidemics.

The Takeaway on COP30 and Yellow Fever

The deeper lesson is that outbreaks emerge when the natural order frays. When forests are destroyed, mosquitoes and monkeys move closer to people. If rivers run dry or rainfall patterns change, vectors find new breeding grounds. When temperatures rise, viruses replicate faster. Pathogens once regulated by their environments now slip across ecological and political boundaries with ease.

As delegates gather in Belém, they are not just negotiating emission targets—they are negotiating the health of the planet itself. COP30 offers a chance to treat health and climate as inseparable, to translate decades of scientific warning into coordinated global action. History will ask whether this was the summit at which leaders finally closed the gap between environmental development and human survival—or the summit they fell too short.