Emergency departments act as a societal safety net, but many patients around the world can't access emergency care due to constraints around distance, travel, cost, and even specialty care. During the pandemic, the prevalence of telehealth urgent cares skyrocketed.

This increase in interest during and post-COVID, along with the advancement of telecommunications technologies in recent decades, sets the stage to scale up telehealth to address disparities and access as a global health strategy. In many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the disparities in urban-rural access to health care are especially stark, telehealth can be particularly well suited to help close those gaps. For example, internet hospitals in China—complete with online health, telemedicine, and mobile medical features—are booming.

Across the world, infrastructure and regulatory barriers tend to be the greatest obstacles to telemedicine use, especially in emergency settings—even though some reports estimate that upward of 20 percent of emergency department visits in the United States can be conducted through telehealth.

Some reports estimate that upward of 20 percent of emergency department visits in the United States can be conducted through telehealth

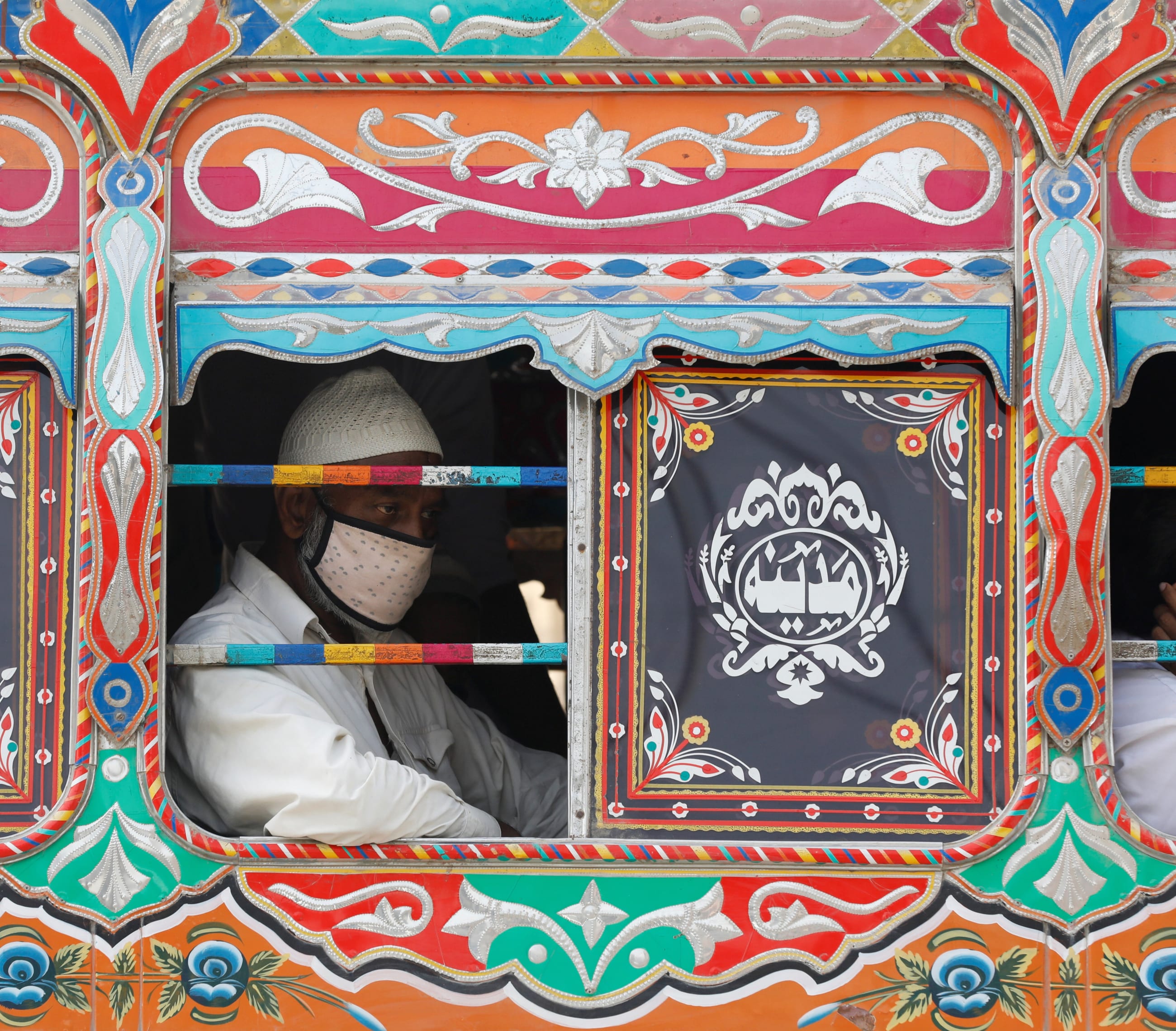

Some countries, such as the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Colombia, have stringent regulations on telehealth. Others, however, including Australia, Austria, and Pakistan, have no regulations at all. Those with minimal regulations lack regulatory infrastructure, but also have one less hurdle as they test remote innovations. Thriving both before and after COVID-19, two telehealth organizations in Pakistan shared their expertise and experiences in using telehealth in resource-poor settings.

Partnering with Local Government

One program has been in development for nearly a decade, Tele Tabeeb. Originally part of the Aman Foundation, a private nonprofit, it shifted to a collaboration with Sindh Integrated Emergency and Health Services (SIEHS), a program run by the government of Sindh province, in 2021. Since partnering with the government, Tele Tabeeb has expanded to serve anyone from around the country, operating 24/7. Their care is free for all patients.

"Tabeeb is a Persian word that means healer, and the prime purpose of telehealth was to give us services where people cannot easily go to the doctor," Lutaf Mangrio, project development director at Tele Tabeeb, said.

At first, many Pakistanis didn't understand the concept of telehealth and didn't believe that telehealth could provide excellent care. High-literacy groups typically used telehealth services more. To bridge that gap, Mangrio launched a radio campaign to advertise Tele Tabeeb.

"When the radio campaign was on the people were calling [to seek care]," he related. "People are hesitant to talk with the doctors and at the first stage when they start calling [for] the first time."

Each day, Tele Tabeeb receives some five hundred to six hundred calls, many of which result in referrals. For fifty to sixty of those calls, doctors provide complete assessments to the patients. Mangrio also used social media campaigns that educated the public to only call if they need medical advice. This decreased spam calls, which used to make up 50 percent of all calls.

Tele Tabeeb has six health advisors, four doctors, and two mental health counselors on call, but is hoping to expand to increase the number of doctors and add pharmacists and nutritionists. They also have project proposals in the works to add video conferencing features and hope to empower rural health facilities to use Tele Tabeeb.

Even though the service itself is free and landline-to-landline calls are free, mobile calls cost, and some patients have complained that those fees have been a burden to accessing telehealth services. Mangrio said that they are working with the government to reduce the cost for mobile phones.

In 2021, Pakistan introduced the first regulations on telehealth in the country, outlining licensing, training, and platform accreditation requirements. It has little impact, however, because provincial governments are "totally autonomous." A comprehensive telemedicine bill is currently before the provincial assembly.

"If the bill is approved, then we will follow the provincial telemedicine regulations," Mangrio said. "Yes, we are following to some extent the federal telemedicine [guidelines already]."

Most countries, like Pakistan, have minimal regulatory infrastructure for telehealth. Given the increasing popularity of and accessibility to telemedicine, global regulations that outline training for clinicians and uniform standards of quality for telehealth visits are the next step to advancing global virtual care efforts. Policymakers would need to address regulatory and legal issues such as privacy and patient data, in addition to access to broadband and technology.

Provider to Provider Telehealth

Rather than putting patients in touch with providers, the ChildLife Foundation in Karachi pairs rural health providers with experienced physicians in urban centers. Founded in 2011, the privately funded ChildLife Foundation began providing telehealth in 2016. What started off as a tele-resuscitation project became the current Telemedicine Satellite Centers' model.

One of its telehealth control rooms is in Karachi, the other in Lahore. In these cities, where it has an abundance of qualified physicians, Childlife hires and trains them to provide video telehealth consultations to remote regions of the country.

"Remote areas of Pakistan, where two-thirds of the majority of the population live, do not have access to health-care facilities, which people who are living in the major cities have," Abida Hassan, deputy general manager for operations at ChildLife Foundation, said.

ChildLife installs high-resolution cameras in health facilities in remote areas, and a qualified nurse with knowledge on how to consult the Telemedicine Satellite Centers is dispatched to the rural areas. These cameras are connected to a hub where the physicians are available 24/7. When a patient arrives, the nurse enters the patient's basic demographic details and the presenting complaints. Physicians on the other side pick up the phone and see the patient through the camera, which allows them to zoom and pan to see the patient up close.

"The camera is so good that you can see how the pupils are, you know the movement of the pupils, the breathing rate of the patient, the movement of the ribs going up and down," Hassan said. "So that helps the doctor actually review the patient in detail."

The nurse then enters the details of the doctor's consultation and receives the prescription from the doctor. Because hospitals in remote regions often have no electronic system in place, the nurse writes that prescription on a register. The doctor on duty at this rural hospital signs off on the record from the nurse. This helps ChildLife providers avoid possible legal problems. Finally, if needed, the patient is transferred to a partner emergency room.

Connecting Patients to Lifesaving Care

From what Hassan has seen, she says that this model has provided lifesaving and timely care to patients who might not have otherwise survived. This satellite center telehealth model is also connected to a team of staff, including doctors, nurses, and pharmacists, who work at an in-person emergency room that is partnered with the telehealth program.

"We call this a hub and spoke model," she explained. "Emergency rooms established by ChildLife Foundation have fifty to sixty beds for patient care with a resuscitation room and separate neonatal and pediatric areas."

They have given consults through telemedicine to more than two hundred thousand patients thus far, and all of their services are free. With more than one hundred telemedicine satellite centers, all thirty districts of Sindh province as well as thirty-three districts of Balochistan province are covered in their telemedicine network.

At these emergency rooms, specialized physicians, and nurses provide care and have access to high-quality facilities to save patients who might not have otherwise survived. One limitation they found is that sometimes ChildLife recommends that patients to come to their emergency room but the patients cannot afford the transportation costs.

"In the [emergency department], we say that around 50 percent of the mortalities can be saved if there is a state-of-the-art functional [emergency department] working in the vicinity," Hassan said. ChildLife is working to partner with ambulance organizations and other health programs to help patients get transport to the emergency facilities they need.

In one case, Hassan said that a physician at the remote facility attached an oxygen mask to a patient, and the oxygen saturation was not improving. The doctor at the satellite center noticed that the oxygen wasn't switched on and the patient was able to recover.

"These are the minor things, which a physician on the ground can easily miss, but someone who is sitting in a peaceful environment can easily judge and add a value as small as this," she said. "But it has a huge impact on patients."