The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed almost unprecedented scientific research and development mobilization and collaboration among scientists globally to develop safe, effective treatments and vaccines. Thanks to the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID), rapid sharing of the first COVID-19 virus genome sequences across the scientific community was possible. At the global health level, the World Health Organization (WHO) has launched the Solidarity Trial, an international clinical trial launched with seventy-four countries that have either already joined or expressed interest to take part in the trial involving more than 200 patients randomly assigned to one of four different treatments options being tested in Phase III clinical trial studies.

COVID-19 TrialsTracker had identified 1,759 other ongoing coronavirus clinical trials as of May 3, 2020

Even more interesting is the fact that while such randomized clinical trials normally take several years to design and conduct, the duration of this international clinical trial will be reduced by 80 percent. This ongoing trial compares four different treatment options to assess their relative effectiveness against COVID-19. By enrolling patients in multiple countries, the Solidarity Trial aims to rapidly discover whether any of the drugs being tried slow disease progression or improves survival. In addition to the Solidarity Trial, as of May 3, 2020, COVID-19 TrialsTracker had identified 1,759 ongoing clinical trials on COVID-19 in places like China, South Korea, Europe, the United States, and South Africa.

While this global mobilization and collaboration is laudable, there are genuine fears given the tragic history of HIV/AIDS. While HIV/AIDS treatment became widely available in the United States and other high-income countries around 1996, it was not until 2004 that the same treatments became available in low-income countries in general—and sub-Saharan Africa in particular—and only after millions of people had already died from AIDS.

Could this history repeat itself with COVID-19?

One major factor for the long delays in accessing HIV/AIDS treatment in low-income countries was the fact that people in these countries could not afford treatment priced at $20,300 per patient per year in 1996 and $18,300 in 1998 thanks to monopolies granted by patent protection. Could this history repeat itself with COVID-19? We need to take the appropriate steps now to ensure that it doesn't. According to Article 27(1) of the World Trade Organization's Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement, any product developer or inventor can seek and obtain patent protection over a new product for twenty years, irrespective of whether the product is a COVID-19 treatment, a vaccine, or the latest iPhone. In the course of this twenty-year period, the patent-holder can prevent third parties from manufacturing and selling the product, except in very limited situations. As the sole manufacturer and supplier of a product, patent protection offers the patent holder the power to charge any price on the product. Patent protection is the main reason why HIV/AIDS medicines remained unavailable and unaffordable throughout sub-Saharan Africa and other low-income countries for years at the turn of the century. Nothing today stops this deplorable and shameful situation from repeating itself.

As perfectly highlighted in a recent op-ed by Ellen 't Hoen, a researcher at the University Medical Centre Groningen, while it is clear that treatment and perhaps a vaccine will soon emerge out of the numerous ongoing COVIID-19 clinical trials, based on the HIV/AIDS precedent, the mere existence of these health technologies does not guarantee that people will be able to access them. "Pharmaceutical giants will bury treatments in a thicket of patents, making them unaffordable to the world's poorest," she wrote in The Guardian.

Pharmaceutical giants will bury treatments in a thicket of patents

Ellen 't Hoen

Already, Remdesivir, an antiviral medication developed by Gilead in 2009 as a potential treatment for hepatitis C—and later also tried for Ebola with limited success—is currently undergoing clinical trials for COVID-19. Although recent headlines about leaked results of the Remdesivir trial mistakenly published on the WHO website without review revealed it was not associated with clinical or virological benefits in patients with severe Covid-19 symptoms, National Institute of Health clinical trial results of the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial—a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded clinical on Remdesivir—published last week revealed different results. According to preliminary data analysis from a randomized, controlled trial involving 1,063 people hospitalized with advanced COVID-19, those who received Remdesivir recovered faster than people who received a placebo. As we await more detailed information on these contradictory trial results, Remdesivir remains one of the world's most anticipated potential post-infection treatments for COVID-19. Until the results are in, it's not clear whether Remdesivir or any other medicine currently undergoing clinical trials for COVID-19 will meet safety, efficacy, and quality standards and obtain the necessary market authorizations anytime soon, but if and when they do, patent protection would pose a significant barrier for low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa and across the world). For example, Gilead's patents on Remdesivir across the world would last until 2038. In fact, any medicine or vaccine that eventually gets approved for COVID-19 treatment or prevention would be patented and subjected to twenty years patent monopoly, posing a significant access problem for low-income countries in general and sub-Saharan Africa in particular.

In a bid to avoid this and to ensure that the HIV/AIDS scenario does not repeat itself, leading human rights, global health, and civil society organizations—as well as global health experts and research institutions across the world—have mobilized to demand that Gilead ensures the availability, affordability, and accessibility of Remdesivir to all across the world if it is proved to be safe and efficacious for COVID-19. Given that Gilead owns the patent to Remdesivir, Gilead alone has the exclusive right to manufacture and commercialize Remdesivir across the world. These groups have called on Gilead to, among other measures, refrain from enforcing its patent and other exclusive rights. This would enable other pharmaceutical companies to quickly develop generic versions of Remdesivir to ensure its rapid worldwide and timely availability to address the current global pandemic. In addition to this laudable and proactive call, President Carlos Alvarado Quesada of Costa Rica has appealed to the WHO Director-General to "pool rights to technologies that are useful for the detection, prevention, control and treatment of the COVID-19 pandemic."

Pool rights to technologies that are useful for the detection, prevention, control and treatment of the COVID-19 pandemic

President Carlos Alvarado Quesada of Costa Rica

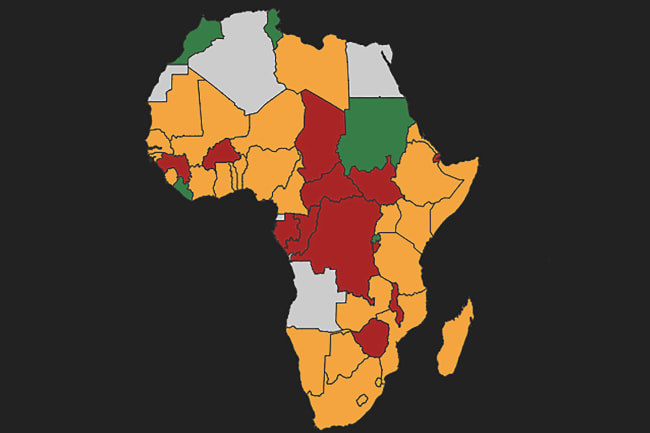

While other governments are considering different measures to ensure patents do not pose a barrier to accessing any medicines approved for the treatment of COVID-19, it makes me sad to know that twelve of the least developed countries of the African Intellectual Property Organization (OAPI) continue to grant patent protection on pharmaceutical products. With the exception of Comoros, all of the least developed countries in the African Intellectual Property Organization are members of the World Trade Organization (WTO), hence, are bound by the WTO's Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights agreement. On November 6, 2015, based on article 66 of the this agreement, the WTO council that oversees this agreement, extended the waiver allowing its least developed country members to abstain from granting and enforcing intellectual property rights (such as patents and clinical trial data protection) on pharmaceutical products until 2033.

Simply put, least developed countries in general, and Africa's least developed countries in particular, are not required to grant and/or enforce patent protection on Remdesivir or any other pharmaceutical product until 2033. This includes: Benin, Guinea Bissau, Burkina Faso, Mali, Central African Republic, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Chad, Togo, and Guinea. Now more than ever, these nations must use the least developed country extension with respect to patents on pharmaceutical products and abstain from granting patents on all pharmaceutical products just like Uganda did in 2019.

Where such patents have already been granted, these heads of states should revoke them

Who should heed this call in the context of COVID-19? For one, all the heads of state of these least developed countries in Africa, namely: Benin President Patrice Guillaume Athanase Talon, Guinea-Bissau President Umaro Mokhtar Sissoco Embaló, Burkina Faso President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, Mali President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, Central African Republic President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, Mauritania President Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, Niger President Mahamadou Issoufou, Senegal President Macky Sall, Chad President General Idriss Déby Itno, Togo President Faure Essozimna Gnassingbé Eyadéma, and Guinea President Alpha Condé. Their countries should follow Uganda's lead and declare that they will henceforth neither grant nor enforce patents or other forms of intellectual property rights on any pharmaceutical product relating to COVID-19 detection, prevention, control, and treatment—and protections in place on other relevant pharmaceutical products as well. Where such patents have already been granted, these heads of states should revoke them.

Together with African Intellectual Property Organization Director-General Denis Loukou Bohoussou, these heads of state must invoke the least developed country extension to enable the import of generic versions of Remdesivir and other drugs if and when they are approved as effective treatments against COVID-19 to combat the ongoing global pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Now is the time for the above-named heads of states and the officials to put the interests of fellow Africans at the forefront.