From the start, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been at the center of the COVID-19 storm—and the target of criticism. The pandemic and the controversies associated with it have created an immediate crisis for WHO as COVID-19 rages on. But it's also created a prospective crisis because the outbreak and political reactions to it will shape the future of WHO. The present back-and-forth between WHO's critics and defenders previews the coming tussle over how to repair global health governance and reform WHO in light of this disaster. Although the pandemic is not over, the pillory and praise of WHO are worth exploring now so that the coming tsunami of demands for change do not destroy the organization in order to save it.

WHO and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Much of the criticism of WHO asserts that it failed to exercise global health leadership and instead became a tool of Chinese politics, power, and propaganda. This critique holds that WHO had the ability to question China's handling of the outbreak in Wuhan so that the organization could better prepare the world for a dangerous disease—but that WHO failed to act decisively. The criticism raises questions about WHO's authority to challenge states during serious outbreaks for the good of global health. In contrast, praise for WHO often highlights how it has its deployed scientific skills, epidemiological expertise, medical know-how, outbreak-response capacities, and global networks in helping China and other countries. These commendations emphasize the imperative for WHO to work with governments in battling outbreaks.

In essence, WHO's critics and defenders are talking past each other. But both perspectives are core to the International Health Regulations (IHR), the leading international agreement on infectious diseases and other serious disease events adopted by WHO member states in 2005.

Deploying these capabilities tends not to generate political problems because the focus is on fighting outbreaks

The IHR's success depends on WHO using its scientific, medical, and public health capabilities to help countries prevent, protect against, and respond to disease events. Deploying these capabilities tends not to generate political problems because the focus is on fighting outbreaks with measures based in science, medicine, and public health. This pattern appears again in the COVID-19 pandemic. WHO's efforts to advance development of coronavirus vaccines and therapeutics have not generated acrimony. The organization's sharing of information and its attempts to counter online misinformation and disinformation have earned widespread praise. The medical and public health expertise that WHO can offer countries to combat COVID-19 is appreciated. Its warnings about the pandemic's threat to low-income countries are acknowledged as important.

Authority of the World Health Organization to Take Action

International Health Regulations grant the ability to challenge how governments exercise sovereignty

The IHR also grants WHO the authority to take actions that can challenge how governments exercise sovereignty. First, the IHR authorizes WHO to collect disease-event information from non-governmental sources, seek verification from governments about such information, and, if necessary, share the information with other states. Second, the IHR grants the WHO director-general the power to declare a public health emergency of international concern, even if the state experiencing the outbreak objects. Third, the IHR gives WHO the authority to reinforce the requirement that a state party shall provide the scientific and public health justification for trade or travel restrictions that do not conform to WHO recommendations or accepted disease-control measures. Fourth, the IHR requires states parties to protect human rights when managing disease events—protections for which WHO, as a champion of a human-rights approach to health, is a leading guardian.

Claims that WHO turned a blind eye to China's dissembling about its outbreak suggest that WHO failed to act on information it had from other sources

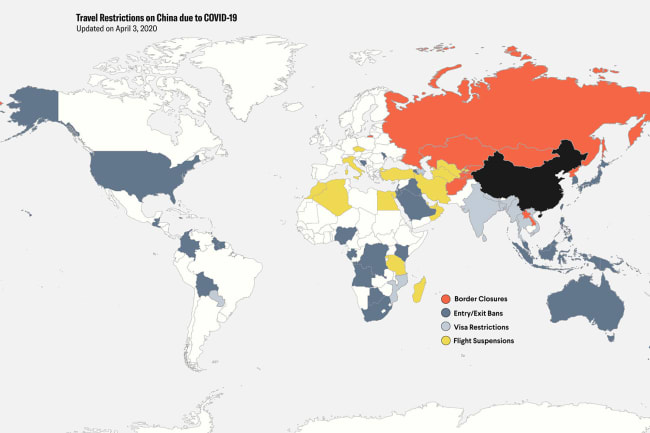

Criticism of WHO during the COVID-19 pandemic has emerged exactly in the context of these authorities. Claims that WHO turned a blind eye to China's dissembling about its outbreak suggest that WHO failed to act on information it had from other sources, including the failure to share that information with other countries. Critics pilloried WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus for declaring the COVID-19 outbreak in China a public health emergency of international concern at a time and in a manner that appeared indecisive and deferential to the Chinese government. The explosion of travel restrictions that countries implemented to counter COVID-19 prompted arguments that these restrictions violated the IHR, violations that the WHO did not probe despite having authority to do so. Complaints also arose about WHO's silence in the face of the human rights consequences of harsh government responses, such as mandatory quarantine and isolation measures.

A Tale of Two Decades: WHO and the IHR

Explaining why criticism and praise of WHO's performance focus on different aspects of the IHR requires understanding how perspectives at WHO and among global health experts about the role of these regulations in global health governance have shifted. The initial decade of this century witnessed astonishing changes in global health that reflected heightened political interest from state and non-state actors, policy and governance innovation, and unprecedented levels of funding. These changes include the transformation of international law on infectious diseases accomplished with the adoption of the IHR in 2005.

The first test after the International Health Regulations entered into force was the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009.

WHO leadership during the SARS pandemic in 2003 made this transformation possible. The WHO Director-General, Gro Brundtland, confronted China over its SARS outbreak and, without approval from the countries concerned, issued warnings against travel to SARS-affected places. Brundtland acted without authority to take these steps. In addition, WHO took the lead in efforts to advance scientific understanding of the SARS coronavirus, develop public health strategies, and establish clinical treatment protocols. In adopting the IHR in the aftermath of SARS, WHO member states gave WHO unprecedented authority vis-à-vis state sovereignty and expanded the need for WHO's scientific, medical, and public health capabilities.

The first test after the IHR entered into force in 2007 was the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009. The WHO Director-General, Margaret Chan, declared the world's first public health emergency of international concern and issued recommendations that, among other things, advised against trade and travel measures. WHO coordinated scientific, medical, and public health efforts to understand the H1N1 virus, share information, treat people, and develop a vaccine. Post-pandemic analysis identified problems with WHO's performance and the IHR's functioning, but, overall, the response underscored the importance of WHO's leadership and functional capabilities and the IHR's role in global health governance.

However, controversies about WHO's leadership, the organization's capabilities, and the IHR dominated the conversation over the next decade. Concerns began after the H1N1 pandemic as WHO and its member states struggled from the damage done by the Great Recession. Facing a financial crisis, WHO cut the budget for its outbreak preparedness and response capacities, and distracted by economic turmoil, member states showed little interest in the recommendations made after the H1N1 pandemic to strengthen WHO and bolster the IHR.

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014 was a disaster for WHO and the International Health Regulations

Then came the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, which was a disaster for WHO and the IHR. WHO's response was so bad that UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon created an ad hoc emergency response effort. WHO Director-General Chan failed to act on information that WHO had received from non-governmental sources, did not challenge governments that wanted to keep the outbreak quiet, and only declared a public health emergency of international concern after the epidemic was already a crisis. Numerous governments flouted WHO recommendations by enacting travel restrictions, and the crisis exposed poor IHR implementation around the world. Reviews of the Ebola outbreak criticized WHO's performance and recommended that the organization exercise political leadership under the IHR and strengthen its capabilities to respond to serious disease events.

The next major crisis was an Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo that started in late 2018. WHO's response to this outbreak demonstrated that it had re-invigorated its functional capacities. Indeed, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with WHO's help, brought the outbreak under control in difficult circumstances during 2019, with an anticipated declaration of the end of the outbreak expected this month.

Director-General Tedros eventually declared a public health emergency of international concern—but only after the outbreak became even more dangerous

However, WHO's response to the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo exhibited resistance to exercising the power to declare a public health emergency under the IHR. A controversy emerged when the emergency committee—established under the IHR to advise the director-general on whether to declare a public health emergency —repeatedly concluded that the worsening outbreak did not qualify as a public health emergency of international concern. For many, the emergency committee's reasoning, which Director-General Tedros accepted, did not accord with the IHR. Director-General Tedros eventually declared a public health emergency of international concern—but only after the outbreak became even more dangerous.

Lost in this back-and-forth over the IHR was something important—global health leaders expressed, and based their actions on, skepticism about key aspects of the IHR. The outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo increased interest in the director-general having more options than the "declaration, no declaration" choice that the IHR provides. The emergency committee's assertions that countries would implement unjustified measures after a declaration of a public health emergency of international concern suggested the committee believed that the exercise of this authority would do more harm than good. The committee also clearly had no confidence in the IHR rules designed to address problematic trade and travel measures imposed in response to outbreaks. In the end, the controversies about the IHR distracted from WHO's impressive on-the-ground efforts to help the Democratic Republic of the Congo overcome Ebola.

This Pandemic was Politicized Before it Started

Understanding WHO's behavior over the past decade helps us see that, before the novel coronavirus emerged in Wuhan, WHO was predisposed for global health reasons to exhibit leadership through deployment of its functional capabilities rather than by exercising authority it had to challenge governments politically. Leaving aside this strategy's merits, the approach put WHO in a difficult position with COVID-19 because the disease emerged into a context that was already hyper-politicized within and beyond China.

China had imposed at home and promoted abroad a version of sovereignty intolerant of domestic dissent and foreign criticism

Well before the Wuhan outbreak, China had imposed at home and promoted abroad a version of sovereignty intolerant of domestic dissent and foreign criticism. China's perspective on sovereignty constituted one of the most important features of the country's rise to great-power status and its global ambitions. For China, the outbreak's domestic and international implications were so serious that the response, including WHO's involvement, had to reflect China's position on sovereignty and its global stature.

Unsurprisingly, the official narratives from the Chinese government and WHO about the outbreak response scrupulously reflected China's political requirements and calculations. This outcome reflects the convergence of WHO's non-confrontational approach and China's intolerance of any divergence from the party line. This convergence meant China's political needs overwhelmed WHO's desire to avoid politics in working with China in the interests of global health, leaving the organization vulnerable to questions about its interactions with China.

China's political needs overwhelmed WHO's desire to avoid politics in working with China in the interests of global health

Other countries—especially the United States—that are wary of China's expanding power and intentions were also primed to interpret this disease event through a political lens. From the beginning, commentary in the United States framed the epidemic in China in geopolitical terms, used it to blame China's political leaders and system for the tragedy, and faulted WHO for complicity with China's perceived deception and propaganda. Such criticism implies that WHO's interactions with China should have reflected U.S. political perspectives rather than China's. The lack of convergence between U.S. interests and WHO's actions left WHO exposed to attacks that intensified as the United States struggled with COVID-19 once it reached American shores.

The Westphalian Virus

Once upon a time, I called the coronavirus behind the SARS pandemic the world's first "post-Westphalian pathogen." In the wake of SARS, WHO member states empowered WHO to challenge sovereignty—the centerpiece of the state-centric, "Westphalian" international order—in the interests of protecting global health. Today, in the COVID-19 pandemic, the world's most powerful countries are demanding that WHO follow their respective sovereign interests for reasons that have little to do with global health. WHO finds itself in this predicament despite, over the last decade, defining its leadership in global health more through its scientific, medical, and public health capabilities than its authority to challenge states politically under the IHR.

The manner in which China and the United States politicized COVID-19 for geopolitical purposes bodes ill for international health cooperation

We do not know whether WHO's functional contributions to the COVID-19 fight will protect it from recriminations about its interactions with China when the pandemic ends and the world evaluates this disaster. The manner in which China and the United States politicized COVID-19 for geopolitical purposes bodes ill for international health cooperation. What happened in this pandemic is a harbinger for what WHO will confront and have to navigate over the next decade. Further, balance-of-power politics will shape WHO's future as much or more than the well-intentioned recommendations that post-pandemic reviews by experts will produce.

In this sense, COVID-19 has not changed the world as much as clarified how much the world has changed since the first decade of this century. Perhaps, then, the acrimony over what to call the novel coronavirus behind the pandemic should be ended by dubbing it the "Westphalian virus."