In early August, at the Africa Health Sovereignty Summit in Accra, Ghana, World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus emphasized the need to "chart a new course for health financing" and that health taxes on alcohol, sugary drinks, and tobacco could serve as a practical solution.

As Africa faces mounting public health threats and tightened domestic budgets, its governments face a critical window of opportunity to mobilize around these underutilized money streams and optimize their value for improving fiscal and population health.

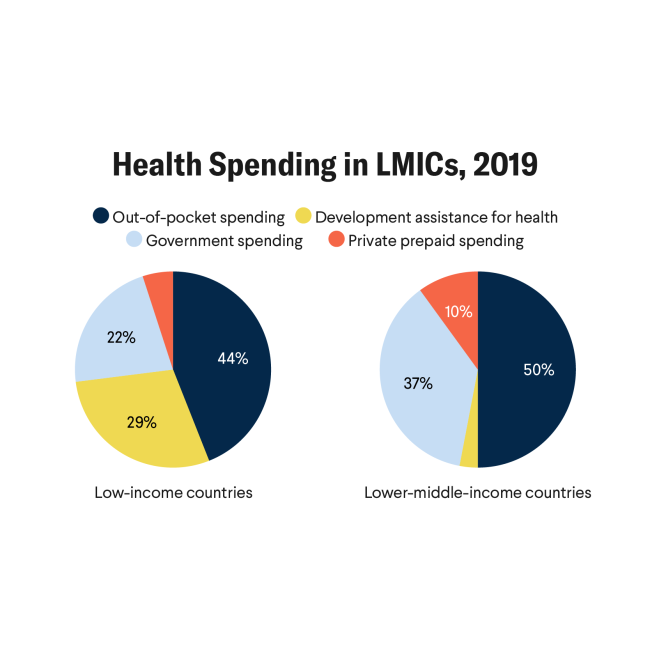

Across the continent, noncommunicable diseases account for more than one-third (37%) of deaths, and today's health-care systems are ill equipped to care for patients with these conditions. The financial shortfall weighs heavily on households: Out-of-pocket payments push more than 150 million people—roughly 1 in 8 Africans—into or deeper into poverty.

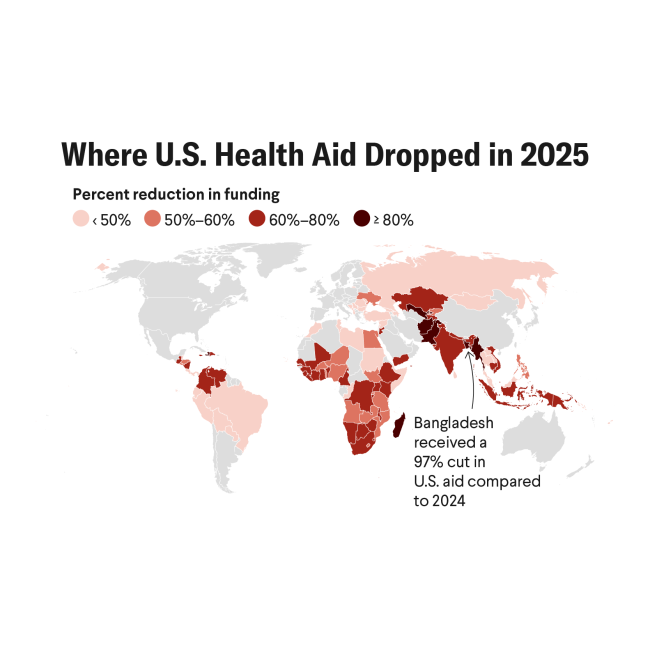

Development assistance for health in Africa—provided by the United States and other governments—is projected to fall by 70%, from $80 billion in 2021 to $24 billion in 2025. In countries where donor funding once accounted for 30% of total health spending, the consequences have been severe: Clinic closures, suspension of outbreak surveillance programs, and reduced HIV and nutrition services have become commonplace.

Across the continent, people are demanding greater protection for health as well as improved health care

These health quandaries—coupled with increasing public debt, more frequent climate emergencies, persistent humanitarian crises, and competing budget priorities—demand new sources of sustainable domestic revenue.

Health taxes offer a triple win. Estimates suggest a 50% price increase on tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverages could save 50 million lives in 50 years and raise $2.1 trillion in five years for low- or middle-income countries. That revenue amounts to 40% of the nations' total health spending.

Room to Grow Health Taxes

Although nearly 90% of African countries have at least one health tax implemented, according to the World Health Organization, fewer than 5% of those countries have met the recommended thresholds for any of the three products: tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages. African countries have some of the greatest potential for untapped revenue and every opportunity to reduce NCDs.

Most governments are collecting less than 40% of the retail price in cigarette taxes [PDF]—far below the WHO-recommended 70% to 75%. However, meeting WHO's recommended tax benchmarks is within reach, as outlined in a new brief from Vital Strategies.

A 2023 policy in Ghana increased tobacco's tax share of the retail price from 23% in 2020 to 38% in 2024, and tax revenue more than doubled. Although Kenya's alcohol excise tax rates are relatively low, the country has developed a rigorous track-and-trace system to reduce illicit trafficking of alcohol, tobacco, and sugar-sweetened products and increase tax revenues. South Africa's 2018 excise tax on sugary drinks resulted in a 29% reduction in taxed beverage purchases per person. The tax raised approximately 5.8 billion rand ($319 million) in the first two years.

To accelerate progress on health taxes, governments need to address three persistent challenges that have stalled the reform that can put countries on a path toward economic sovereignty and healthier lives: country-specific data, coordination across sectors, and—most of all—countering industry interference and misinformation.

Country-specific data. Policymakers increasingly demand local evidence to justify reforms, especially when concerns linger about revenue impact or public resistance. However, limited access to reliable, real-time data on pricing, consumption, and health costs often delays decision-making.

Open-access modeling tools are beginning to close this gap by enabling context-specific estimates to support national dialogue. For example, local purchasing data helped motivate policymakers in South Africa to pass the Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Health Promotion Levy because research showed significant reductions in sugar, calories, and volumes of taxed drinks purchased after both the initial policy announcement and enactment.

Coordination across sectors. Another key challenge is making health taxes a coordinated, high-priority government effort, bringing together finance, health, trade, agriculture, infotech, and communication ministries to collaborate on shared goals.

Successful reforms in countries such as South Africa and Ethiopia didn't rely solely on expertise: They were propelled by cross-ministerial task forces and political champions who converted potential into action.

For example, Ethiopia's June 2025 workshop brought together Parliament, the Health Ministry, finance, WHO, and the Inter-Parliamentary Union to translate intent into policy—complete with budget alignment, timing coordination, and a unified communication strategy to preempt interference from vested interests.

Countering industry interference and misinformation. Tobacco and alcohol companies in particular operate with considerable influence across African markets, often using misleading and self-interested economic arguments to oppose policy reform, engaging in "corporate social responsibility" schemes to enhance their public image, and using litigation or threats of it to intimidate policymakers.

For example, in Nigeria, tobacco industry influence extends to membership on the national standards board. In Zambia, interference has blocked tobacco control legislation since 2009. Officials in Ethiopia cite unsubstantiated illicit trade fears to resist tax reform, and threats of litigation and fearmongering about job losses in Ghana were used to delay stronger tobacco taxes.

Multinational companies that sell alcohol, sugary drinks, and tobacco seek to cloud the issue by advancing myths about job losses, regressivity, and illicit trade. But global evidence shows that well-designed taxes can reduce harm [PDF] and have a positive economic impact. Often the public supports health taxes, especially if the revenue is used to fund health and social programs. Recent polls reveal strong public support for bold fiscal health measures. In Kenya, 65% of people favor higher alcohol taxes, and 85% do when revenue is explicitly allocated for health services.

Across the continent, people are demanding greater protection for health as well as improved health care. Can governments meet this moment and put the public's health above private profits? The time is ripe to fix the price tag on health.

Several African countries from the islands of Cabo Verde to Ghana are moving beyond rhetoric, demonstrating that health taxes are realistic and revenue-rich opportunities. The road ahead is clear: Health taxes offer policymakers an opportunity to unlock transformative resources for health systems, tackle the growing burden of preventable disease in Africa and improve people's lives—right now.