On Thursday, the required one-year notice period passed since the United States declared its intention to leave the World Health Organization (WHO), although other member states continue to discuss the U.S. exit given that the country has yet to pay its outstanding assessed dues.

When President Donald Trump announced the departure on the first day of his second tenure, I hoped that a quick deal could be reached. I was wrong. Last May I wrote in the New York Times, "The golden age of global health as led by the United States is over. The rest of the world must now focus on building a healthier world that is less dependent on U.S. aid—and less susceptible to U.S. influence and disruption. Greater self-reliance is the path to truly sustainable development."

The situation resembles when the Soviet Union withdrew from the WHO in 1949 over philosophical differences in how global health should be pursued, only to return in 1955 following a thaw in relations and governance reforms that gave regions a greater voice.

This history entices one to wonder what it would take for the United States to rejoin the WHO. Multilateralism without one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council is only "partly-lateralism."

The U.S. pullout from the WHO is part of a broader retrenchment from multilateralism. As Secretary of State Marco Rubio wrote in early January 2026, referring to a recent similar U.S. withdrawal from 66 international organizations: "This does not mean America is turning its back on the world. We are simply rejecting an outdated model of multilateralism—one that treats the American taxpayer as the world's underwriter for a sprawling architecture of global governance." He continued that the most important criterion for the country is the "ability to help us achieve U.S. national interests." Such remarks speak to the essence of the America First Global Health Strategy.

This history entices one to wonder what it would take for the United States to rejoin WHO

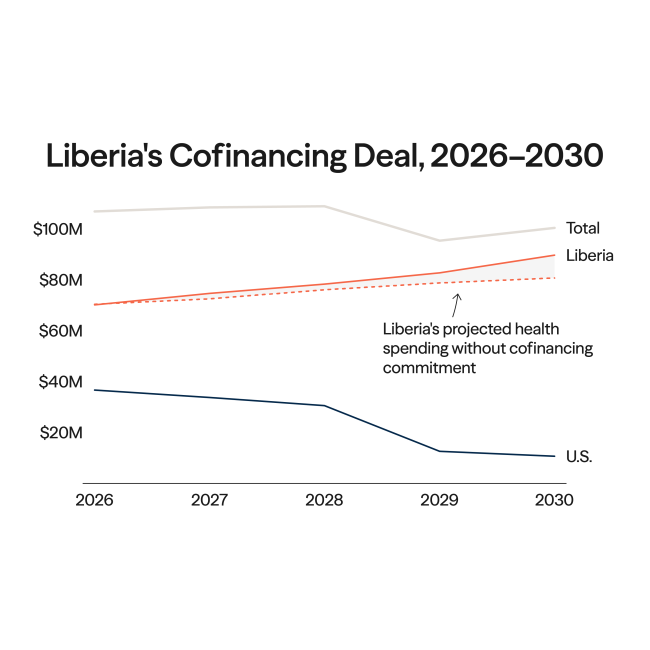

At the same time the United States is recoiling from multilateralism, it is leaning on bilateral agreements in global health. As of mid-January, 15 African countries have signed. There is much to appreciate about these deals: their focus on country accountability and domestic finance, and their emphasis on data and innovation. Other facets are undesirable: the abrupt transition in aid which is costing lives, the neglect of noncommunicable diseases which are a priority for many countries, the potential to exploit national data, and the single-minded emphasis on U.S. innovation which risks minimizing a country's own economic development. The weakest part of the America First Global Health Strategy was the section on pandemics. Because these emergencies can start anywhere, a multilateral approach involving all countries is needed. Global health security is squarely in the U.S. national interest.

The deeper question is what reforms triggered by the United States would strengthen the WHO and global health regardless of whether Washington returns. I see three arenas: accountability, innovation, and trust.

Accountability

Most fundamentally, a U.S. return to the World Health Organization would require greater accountability. In his recent statement, Secretary Rubio says, "The Trump Administration is demanding real results from the institutions we fund and participate in, and we stand ready to lead a campaign for reform."

The importance of accountability is evident—both at global and country level—in universal health coverage (UHC), where little progress has been made over the past decade. Every two years since 2015, the WHO and the World Bank publish a UHC global monitoring report, and each iteration has more or less stated the same thing: only about half the world has access to UHC, and we need to do better. None have stated the obvious: hey, you've said this every two years for a decade—what gives? At the launch of the latest report, in Tokyo on December 6, Nigerian Health Minister Muhammad Pate emphasized the solution: accountability at the country level, saying, "without it we cannot hold ourselves accountable and we cannot hold others accountable."

WHO has already built many of the technical tools needed for this level of accountability—but it has struggled to embed them institutionally. The organization has developed tools to measure the outcomes it supported in countries, manage the outputs it produced to do so, and even assess how the different multilateral agencies supported countries. However, where this strategy faltered was in the lack of a sustained focus on results and the inability to transform governance.

The opportunity now is for WHO to revitalize this results agenda, not just for its organizational goals but also to support countries in their efforts to become more accountable for results.

Innovation

Innovation is vital in global health because it drives better health and economic development. The bilateral agreements show a strong focus on promoting U.S. product innovation, starting with the newly approved lenacapavir, a twice-yearly preventive injection for HIV.

These deals could be complemented by innovative services—which might be where the best opportunities for countries' economic development lie. Innovations such as Tanzania's m-mama emergency transport system, community-based mental health therapy in Zimbabwe and Uganda, and Hewatele's low-cost oxygen distribution system in East Africa show that innovative, scalable, and locally led solutions are possible and vital.

The opportunity for the WHO is to become a key scaler of these innovations. The organization's pre-qualification process already enables innovative products. However, it could do more to help with so-called horizontal scaling—across countries—of service delivery models. There is no other organization working in more than 190 countries that could do so.

If the WHO is to take scaling seriously, innovation must extend beyond technologies and services to the way health is financed. The WHO has helped countries with loans from regional development banks through the Health Impact Investment Platform. This little-known role as an enabler of innovative finance points a way forward.

Trust

Finally, a U.S. return would require building trust. Initial U.S. objections to the WHO centered on "the organization's mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic that arose out of Wuhan, China, and other global health crises, its failure to adopt urgently needed reforms, and its inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence of WHO member states."

The WHO's decisions on the origins of the pandemic, mode of transmission, and its recommendations on public health measures and quarantine—even when defensible on scientific grounds—contributed to controversy and appear to have affected trust among governments and publics alike.

I have argued that in public health crises, institutions should actively seek to challenge their own internal decision-making. Red-teaming involves assembling a group that takes on the role of adversary, tasked with challenging the assumptions, strategies, and plans of an organization.

Organizations such as the WHO could also monitor public trust in their activities using established survey methods. A study conducted by the Council on Foreign Relations and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation showed that trust was related to pandemic outcomes such as cases and mortality. Managing trust alongside other outcomes could enable more holistic decision-making and avoid the post-COVID repercussions the WHO is witnessing now.

Yet institutional trust is shaped not only by technical decision-making during crises but also by whether the WHO is perceived as politically even-handed. Successive U.S. administrations have expressed concerns about disproportionate scrutiny of Israel across parts of the UN system. Recent political events offer a litmus test. If an organization appears to focus more on attacks against health facilities by Israel than on credible allegations of the militarization of those facilities by Hamas, that risks undermining perceptions of neutrality. If it appears to devote more attention to attacks against health facilities by Israel than to comparable attacks by the Islamic Republic of Iran against its own population, that too can erode confidence. And if some crises receive sustained institutional attention while others with comparable or greater mortality receive less, questions about consistency inevitably arise.

WHO has performed better than several other UN bodies in this regard. Still, a systematic independent assessment of how the WHO applies principles of neutrality across different conflicts would be valuable—just as one would audit any other valuable activity. Neutrality is a foundational UN value, and strengthening confidence in its consistent application should be a priority.

A Way Forward

These proposals—on accountability, innovation, and trust—are different from the current budgetary retrenchment at the WHO, which has a back-to-basics feel. Rather, they would better position the WHO for the new era of global health, where the organization could support countries' "sustainable self-reliance" more effectively. They also position the WHO to collaborate more effectively with the United States—and potentially to compete with alternative organizations should the "Board of Peace" remaking of global governance ever extend to health. One thing is sure: we live at a time of rupture in the world order, and it will have further implications for global health.

The current WHO director general has acted honorably on these questions as well as with the U.S.–WHO relationship. At the same time, the election of a new director general in May 2027 offers an opportunity to revisit these issues. The ideal candidate would be one who underscores country ownership, revitalizes the WHO's results agenda, promotes the organization as the world's leading scaler of health innovations, makes the WHO the most neutral organization in the UN system, and establishes mechanisms to protect trust in pandemics.

By doing so, they just might bring the United States back into the WHO.