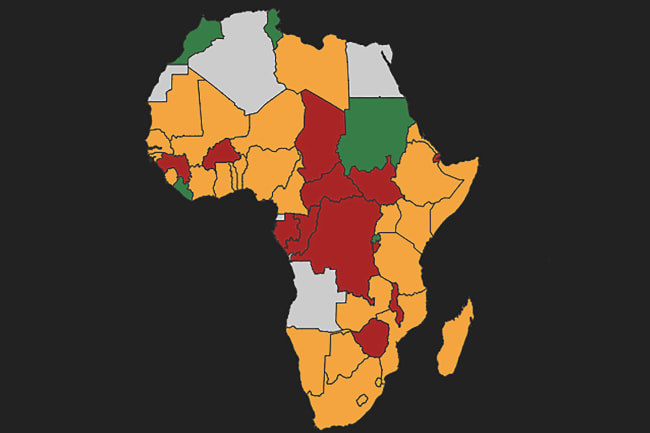

On the evening of Sunday March 15, as the COVID-19 virus continued its destructive advance around the world, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa declared a "national state of disaster." By Wednesday, the number of confirmed infections reached 116 in the country. Across the continent, there were reportedly more than 600 confirmed infections in 33 countries—far more by the time you read this—many hitting with weak health systems and vulnerable citizens already grappling with other serious diseases.

As in the United States, it is not yet clear how severe the pandemic will become in South Africa or across the African continent, but already the numbers of those testing positive for coronavirus are steadily rising.

Seldom has there been a stronger argument for U.S. global engagement to strengthen African health systems

——— Michael Gerson

Our fate in the United States is tied to that of people around the world. As we distance ourselves physically, we cannot forget how we are connected. In the coming months, the United States may bring its own coronavirus epidemic under control with social distancing and other measures. However, if COVID-19 rages in other nations, the United States and the whole world remain at risk. For our long-term safety, other countries must be able to respond effectively. As syndicated columnist Michael Gerson observed last month of the quickly developing pandemic, "Seldom has there been a stronger argument for U.S. global engagement to strengthen African health systems."

Of course, our connection to people in Africa and other continents is not just about the ease with which COVID-19 spreads. It is about our humanitarian concern with our neighbors close to home and far away. That is the spirit of U.S. leadership in global health. The considerable investments we make in tackling long-term epidemics like HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), and malaria have multiple direct benefits for Americans, but first and foremost they are about saving lives and making life better for communities hard hit by disease.

Nearly three million people died of HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria in 2018. People now living with those diseases are likely at elevated risk from coronavirus. There is real concern that COVID-19 could undermine efforts to address these and other critical health priorities by disrupting medical supply chains and putting major strains on health systems. As we marshal a domestic and global response to this current health crisis, it is important to remember that an ultimately successful effort includes protecting other essential areas of public health, including the effort against today's biggest infectious disease killers: HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria.

The presence of these programs in Africa is lending a critical hand in this new, unfolding crisis

For the U.S., pandemic preparedness and response is about immediate domestic efforts and much broader, long-term investments in global health readiness. Programs like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the USAID TB Program, and the President's Malaria Initiative not only fight specific scourges, but they also help support human resources, supply chains, laboratories, data management, and other areas of health systems that enable countries to identify and deal with emerging and persisting epidemics. The presence of these programs in Africa is lending a critical hand in this new, unfolding crisis. The Global Fund, for example, has announced that countries can use some of its grant funding to shore up health systems to better tackle COVID-19.

The presidential campaign is an important opportunity to recognize the connections between the health of Americans and that of people around the world. All candidates for president should lay out their plans for a comprehensive effort to advance America's humanitarian priorities and the global impact on our own health security through integrated efforts against new and deadly pathogens and a stepped-up effort to finally end epidemics, including AIDS, TB and malaria, that kill millions each and every year.

On Monday, Ambassador Deborah Birx, a member of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, noted that, "The HIV epidemic was solved by the community, the HIV advocates and activists who stood up when no one was listening and got everyone's attention. We're asking for that same sense of community, to come together and to stand up against this virus."

Now is the time to recognize that our community is the world.