Today, many people meet their doctors on a screen rather than in a clinic. In 2022, the most recent year with data, nearly 1 in 3 U.S. adults reported having a telehealth visit. Hospitals post glossy headshots, telemedicine visits are often recorded, and physicians explain treatments on social media apps such as YouTube, Instagram, and WhatsApp. But danger lurks behind this online visibility, as it creates a huge repository of images and audio that artificial intelligence (AI) systems can use to mimic a doctor's face, voice, and style.

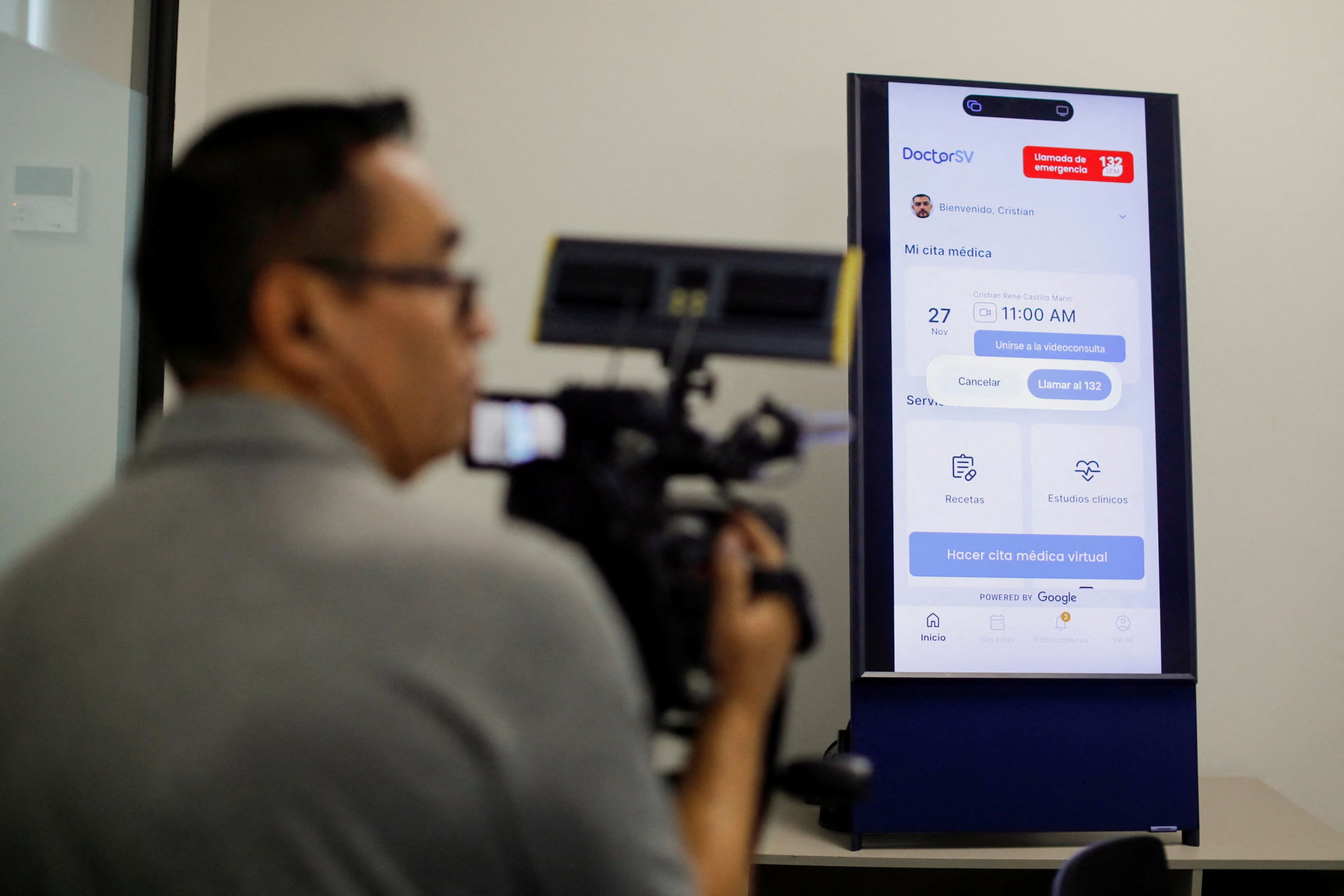

The growing availability of generative AI tools means that anyone with enough content can build a convincing digital "doctor" who looks and sounds like a real clinician. That digital double could appear in a health app, a chatbot, or a social media video, offering medical advice that the real doctor never approved of or saw. News reports are beginning to flag these fakers.

One question for global health is simple and urgent: Who owns that digital doctor? Sports and Hollywood could supply an answer.

In the United States, long-standing rules in college sports once barred athletes from earning money from their own name, image, and likeness (NIL), even as universities and sponsors made millions. However, legal changes in 2021 opened the door for students to sign endorsement deals and license their image based on the idea that their public persona is their property, not a free asset for institutions.

The growing availability of generative AI tools means that anyone with enough content can build a convincing digital "doctor" who looks and sounds like a real clinician

Actors fought a similar battle. During the 2023 strike, the Screen Actors Guild–American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) demanded guardrails on the use of AI-generated "digital doubles" that created the possibility for studios to scan actors' faces and use a synthetic version of them forever. The resulting protections require consent, clear limits on how a digital replica can be used, and compensation when it is.

Taken together, NIL rules and the SAG-AFTRA agreement point toward emerging norms: identity has value, and AI cannot simply harvest it. Physicians now face the same challenge, with one crucial difference: When a doctor's identity is misused, patients can be harmed, and trust in health systems can erode.

How AI Can Misuse Physician Identity

AI-generated content consists of three patterns that have worrying implications for global health. The first is deep-fake endorsement. A Full Fact investigation found hundreds of deep-fake videos impersonating real doctors and other health figures on major platforms. These fraudulent clips can show a well-respected local clinician praising untested treatments, promoting counterfeit medicines, or discouraging vaccination.

For example, NBC Washington found a chatbot that claimed to be a real doctor and provided a real California physician license number that belonged to a real physician. This content poses a serious threat for communities where people know and trust the impersonated doctor, as a believable synthetic could spread harmful advice quickly.

The second risk is the rise of "digital doctor" avatars. Health systems and technology companies are experimenting with virtual clinicians that look and sound like real staff. In principle, these avatars could help explain test results or provide follow-up instructions in multiple languages. Some hospitals are piloting bedside "virtual care" assistants that can deliver scripted instructions through a humanlike on-screen avatar. However, this shows how quickly a clinician's look and voice could be packaged into a reusable digital stand-in. Without clear rules, a doctor's digital twin could continue to be used by the hospital, startup, or foreign platform even after the real clinician has left or changed their mind about the use of their likeness.

The third risk is invisible AI training. Telemedicine platforms and call centers often record calls for quality monitoring and training, and medical education routinely relies on recorded lectures and training videos for instruction and quality improvement. But those same recordings can also be repurposed to improve or train AI systems.

For instance, "ambient" documentation tools explicitly record clinician–patient conversations to generate outputs, and many vendors have sought access to encounter data to improve performance. The Permanente Medical Group reported 2.5 million uses in one year of these ambient AI "scribe" tools, illustrating how quickly large volumes of real clinical speech can accumulate for system improvement or model tuning. In parallel, modern voice-cloning tools can recreate a person's voice from just minutes of audio, making it possible to emulate a doctor's delivery and bedside manner even when the resulting product is presented as a generic AI assistant.

Furthermore, clinical work is no longer bound to one place: Telemedicine visits can be delivered across state and national lines while the "back end" of care, including cloud storage, transcription, quality assurance, and AI development, is often handled by large vendors and subcontractors that operate internationally to cut costs, scale quickly, and reach new markets. However, once recordings, training videos, or clinician likeness and voice data enter those pipelines, they can be copied, processed, and repurposed in jurisdictions with different privacy and publicity rules, creating downstream risks that spread far beyond the clinic where the content was originally created.

If global health policy does not adapt, physicians' identities could quietly become inputs for AI products in the same way that college athletes' personas once fueled video games and broadcasts.

Eroding Trust in Health Care

Misusing physician identity affects both equity and trust. In 2024, KFF Health found that only 29% of U.S. adults trust AI chatbots to provide reliable health information. They also found that fewer than half would trust an AI-enabled health tool to manage their care or to use records to provide personalized advice. A year earlier, Pew Research found that 60% of U.S. adults would feel uncomfortable if their own provider relied on AI to diagnose disease and recommend treatments. When fake or synthetic "doctors" circulate online, patients don't just risk receiving bad advice; they also start doubting the authenticity of legitimate telehealth messages and medical guidance. Furthermore, recent cases where individuals sought high-stakes guidance from chatbots (e.g., drug-use or self-harm discussions) and later died have reinforced public fears that AI advice can fail catastrophically.

However, U.S. national surveys indicate a rapid adoption of health-related AI tools, as 66% of physicians [PDF] claimed they used AI in 2024 compared to only 38% in 2023. This raises new questions about physician data, images, and communication styles. Furthermore, regulation is uneven. Although some high-income countries are starting to regulate AI in health care, many jurisdictions still have few or no rules covering digital likeness, deepfakes, or rights of publicity [PDF]. Protections against deepfakes and misuse of digital likeness remain fragmented and nonharmonized across jurisdictions. These limitations could leave a physician in Lagos or Los Angeles who discovers their clone in a foreign health app with no straightforward legal remedy.

A "Physician NIL" Framework

A new framework could rest on five principles.

First, physicians should retain ownership of their professional identity. Their name, face, and voice should not automatically belong to their employer, health ministry, or any platform through broad contract language. Identity should be defined separately from employment duties, and health institutions should explicitly acknowledge that the likeness of clinicians is not a transferable asset. In addition, structured guidance, analogous to NIL education for athletes, could help clinicians understand how their identity can be used and what protections or negotiations are appropriate.

Second, any AI use of a physician's identity should require informed, opt-in consent. That consent should be specific to where and how a digital avatar or voice clone is used and should be revocable if the risks change or if the physician changes roles.

Third, when a physician's likeness clearly increases the credibility or value of a digital health product, doctors should be able to negotiate fair terms, including compensation and limits on reuse, especially for cross-border deployments in settings with weaker regulations, as there are higher risks of misuse, so contracts should include clear safeguards and remedies.

Fourth, platforms, hospitals, and technology vendors should share responsibility for preventing impersonation. That means clearly labeling AI-generated content, providing rapid ways to report deep-fake health content, and avoiding deployments that blur the line between a real physician and an automated system. This will enable patients to quickly verify who (or what) they're hearing from, which protects trust in legitimate telehealth messages and clinical guidance.

Fifth, physicians should be supported in enforcing and defending their identity rights. Clinicians should be encouraged and given practical tools to understand the relevant procedures and dispute pathways in their jurisdiction. Since misuse may only become visible after deployment, doctors should know how to document harms, trigger takedown processes, pursue institutional remedies, and, when necessary, seek legal relief. Institutions and platforms should provide transparent escalation routes, preserve audit logs, and commit to cooperation with investigations so that enforcement is feasible rather than theoretical.

What Global Health Institutions Can Do Now

Internationally, new protections are emerging but remain uneven. The European Union is moving toward mandatory labeling of AI-generated or manipulated content (including deepfakes), and countries like Germany and France already require consent to publicly share a person's recognizable image.

In low- and middle-income settings, scalability should rely on low-cost, low-bandwidth defaults: standard consent language in routine intake forms, simple "AI-generated" watermarks or verified-source markers that survive compression, and reporting channels that work over different messaging formats. A single complaint should be routed to platforms, medical councils, and regulators at once, while frontline training focuses on basic triage (preserving screenshots/ timestamps, checking official clinician directories, and issuing rapid countermessaging via trusted community channels). Regional regulators can further cut costs by sharing model rules, pooled incident registries, and cross-border escalation pathways.

Furthermore, international and national institutions do not need to wait for perfect laws before acting. This can explicitly include identity protection. National medical associations can also state that knowingly deploying tools that impersonate doctors without consent is unethical.

The Stakes for AI and Trust

As AI reshapes health systems, some may feel pressure to use doctors' faces and voices to make digital tools feel familiar and trustworthy. The experience of college athletes and film actors shows both the risks of doing this without guardrails and the power of collective pushback.

Protecting "Physician NIL" is not about rejecting technology. It is about making sure that the identities patients rely on are not quietly turned into assets that can be bought, sold, and cloned without consent. If global health wants AI to strengthen, rather than undermine, trust in care, it must answer one question clearly: Whose doctor is this, really?