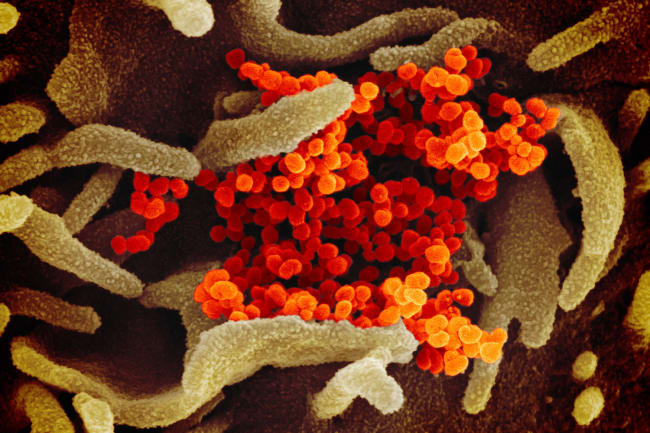

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cuba has agreed to send emergency teams of health care workers to seventeen nations. The United States has added $128 million in funding to fight COVID-19 through global health and humanitarian programs in 120 countries. This is nothing new for either country. Cuba has been known to deploy its health care workers during public health crises for decades, and the U.S. federal government has an even longer, established commitment to funding life-saving work across the globe. However, this unprecedented crisis and its impact both within our country and abroad, underscore the importance of processes and policies that promote collaboration for health, and present an opportunity to ask what lessons the United States can learn from Cuba.

An opportunity to ask what lessons the United States can learn from Cuba

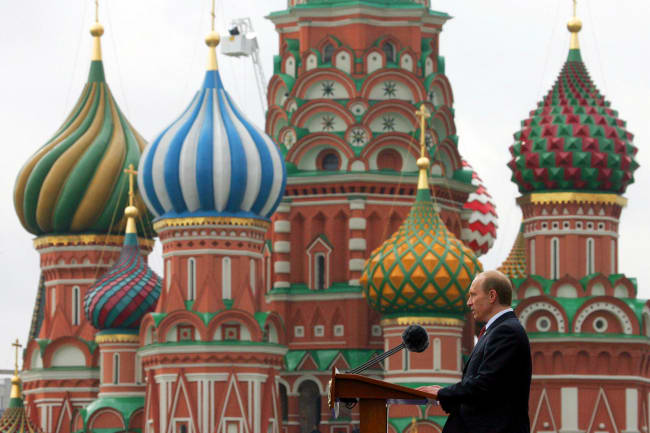

Medical diplomacy is a cornerstone national goal for Cuba, and the country has long championed their commitment to health as a "moral incentive." The small island nation has not only based much of their own health care system on the concept of universal coverage, but has consistently sent their own doctors abroad to other sites during times of need. Notable examples include its response in Chile after an earthquake in 1960, the then-Soviet Union following the Chernobyl explosion in 1986, Indonesia after the 2004 Tsunami, and West African countries to fight Ebola in 2014. The United States also has a long history of supporting its neighbors and other nations during times of need. Eloise Linger, a professor of politics at State University of New York at Old Westbury explained that we employ a "material incentive," such that we expect a "tangible, concrete reward" for our work. Both countries are committed to medical diplomacy, but approach it very differently.

The responses of Cuba and the United States to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and the Dominican Republic, highlight the countries' distinct approaches to global health crises. Cuba trained more than 500 Haitian physicians at no cost, sent more than 6,000 of their own doctors to work, provided almost fifteen million medical consultations, and taught literacy to 165,000 Haitians.

What would happen if the United States expanded its understanding of medical diplomacy beyond funding?

The United States, via the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), sent almost $50 million to Haiti and the Dominican Republic for humanitarian assistance following the disaster. American physicians did volunteer through organizations such as Doctors without Borders, but the federal response was primarily financial—though the United States did employ both economic and human capital in their response to Ebola epidemic a few years later. However, what would happen if the United States expanded its understanding of medical diplomacy beyond funding to focus on true partnership with other countries? Could we consistently combine human capital (e.g., health care workers from another country) and our own financial capital to optimize health benefits and relationships across the globe?

More importantly, the question on all of our minds is whether this would work in a pandemic. We must ask ourselves how we can join with other countries to improve their health benefits without hindering our ability to fight the disease, a challenging endeavor today amidst the coronavirus pandemic. Currently, the United States is facing criticism for its requirement of aid recipients to obtain approval from USAID before using U.S. funds to purchase personal protective equipment (PPE). USAID explained this restriction as a protective measure to ensure that the United States had enough PPE for itself first, demonstrating conflicting priorities between diplomatic relations and our nation's health.

As of June 12, 2020, nearly 114,000 Americans have died of COVID-19

To genuinely prioritize the health of the world, we should consider establishing policies and practices that support collaboration over competition. We do not have time to wait. As of June 12, 2020, nearly 114,000 Americans have died of COVID-19 and more than 421,000 individuals worldwide have died. Likely these numbers are gross undercounts of the true lives lost. The United States must leverage its financial capital and relationships with other countries and among its states through procedural improvements and policy change.

What Does Medical Diplomacy Mean During COVID-19 in the United States?

The United States does not have enough health care workers to meet this unprecedented need for health care. The shortages in sufficient personal protective equipment have left health care workers susceptible to COVID-19 and potentially unable to serve on the frontlines. Moreover, this experience has highlighted the bureaucratic obstacles in allowing foreign-born health care workers to join the fight. These obstacles speak to a greater need for streamlined systems for aid provision and use and the underlying policies that facilitate this.

Bureaucratic obstacles in allowing foreign-born health care workers to join the fight

Ethical questions around achieving health justly and equitably have arisen amidst the response to COVID-19. As the virus spreads, it pays no heed to the number of hospital beds in an American town or the already-immunocompromised nature of certain subpopulations. Not every location or individual is as equipped to handle it. The implications of this are complex and unclear, calling for the application of moral principles and public policy theories to guide policies and interventions.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Going forward, policymakers should consider procedural changes to aid the dispersal of resources. Within the United States, New York City overhauled its volunteer system to create a special one that allowed individuals from across the nation to easily serve during the crisis. They even granted volunteers special access to free housing and travel as needed. What if every state had this sort of disaster response? This would allow for rapid and streamlined mobilization of support to areas dealing with challenging circumstances.

What if every state had this sort of disaster response?

What if health care workers could be mobilized to respond en masse to crises outside the United States? Cuba has long sent its doctors to 'hot zones' of medical need during and after crises. The United States has sent funds, and has a growing shortage of health care workers domestically. However, there is potential to partner with other countries, possibly even Cuba, and explicitly designate funds to move health care workers to places in need. This would specifically protect the United States from "brain drain," or the inability to effectively respond to a crisis due to insufficient numbers of health care workers.

Another key area for policy reform is the certification of foreign doctors or nurses. These essential workers encounter long wait times for green cards, restrictive practices on where they can permanently settle, and rules for where they can work while waiting for their green cards. Like a smoother volunteer registration system, this could be an opportunity for designing a more efficient and effective means of allowing foreign-educated health care workers to work in America.

Ethical Considerations

The ethical implications of medical diplomacy are complicated.

Cuba currently employs more than 28,000 medical staff in sixty countries

Cuba currently employs more than 28,000 medical staff in sixty countries, and it has used these efforts to leverage soft power in its relationships with other countries. However, the country also falls short on the ethical treatment of its own work force. Cuba been heavily criticized for its treatment of these providers. Specific concerns include low pay, separation of the health care workers from their families, and denial of basic rights to speech and movement.

If we were to engage in greater medical diplomacy efforts, there would undoubtedly be questions about addressing issues in our backyard first. That is, in President Donald J. Trump's "Make America Great Again" administration, it would likely be difficult to justify and realize actions to support worldwide health. It's easy to imagine arguments for focusing efforts on dealing with problems in our state and country. But the argument for medical diplomacy is even more compelling. Health has never been more important than during the unprecedented, difficult times of the COVID-19 pandemic, and medical diplomacy could be the best route to health security.

Health has never been more important

We are left asking ourselves what we can do to identify who needs help the most. From this, we can ensure that they, be it a country or state, receive the resources to address this need. COVID-19 underscores the importance of these questions by showing the value of and need for international and state-to-state collaboration, especially during times of strife. This need can be met through better processes and policies to allow health care workers to go where they are needed, guided by an ethical rationale for supporting the health of our nation and our world.