I am an emergency medicine doctor in New York City. I am in my third year of a four-year residency training program at Weill Cornell Medicine and Columbia University Irving Medical Center. In the last two months, as the city became the global epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, my parents, former patients, close friends, and just about anyone I have ever known or loved have all reached out to me to show concern and ask me about my experience. I have received a flurry of calls and long emails at odd hours and at random times between marathon shifts. It has been difficult to fully express what I'm feeling, so I have begun to fill my personal journal with thoughts and emotions. This is a selection of excerpts.

1. The War Zone

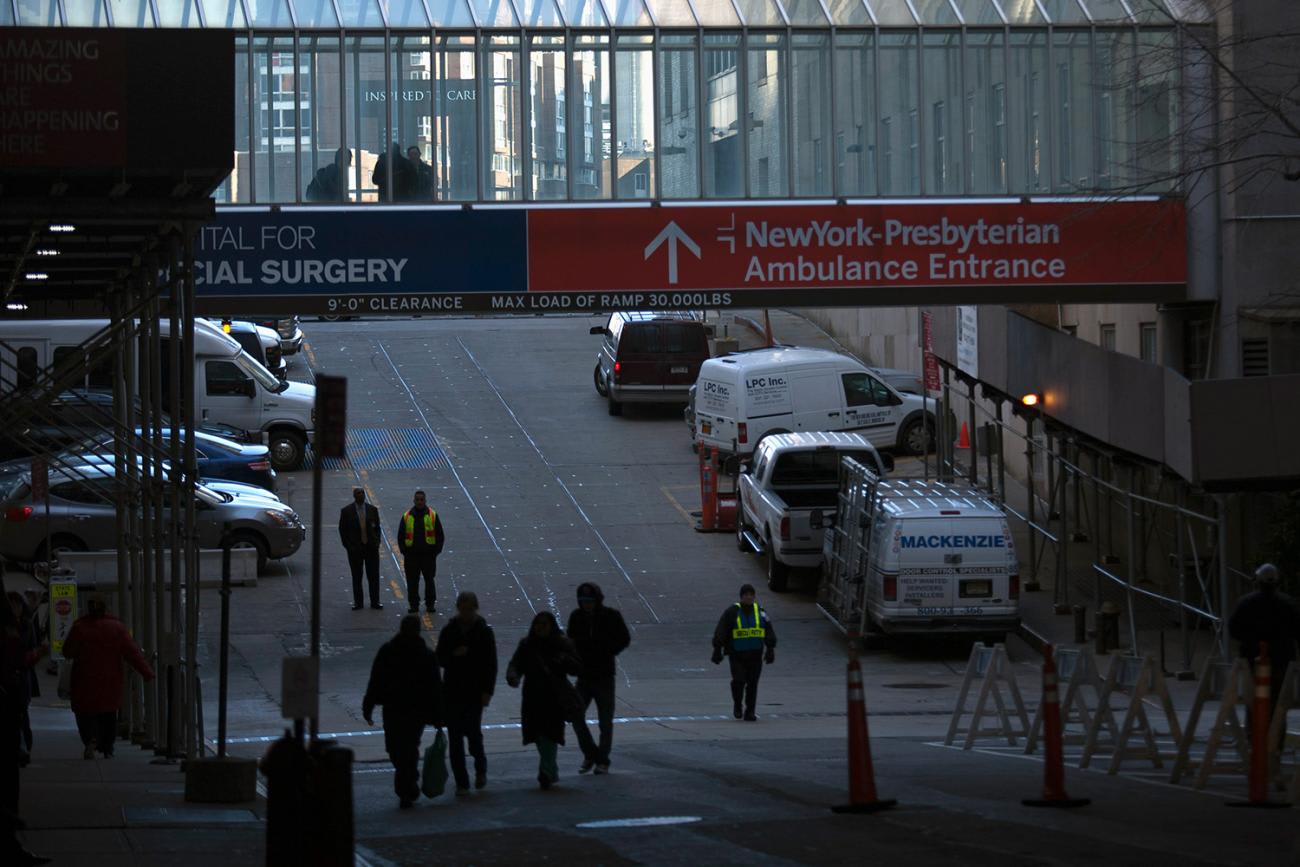

It's 1:55 p.m. The entrance to the ER is surrounded by sirens and dozens of ambulances. A refrigerated truck is being filled with dead bodies without body bags because the hospital has run out, and the morgue is full. This grim reality sets the stage for my upcoming twelve-hour shift.

Less than five minutes into a disaster of a shift, I mutter to myself: "This is armageddon."

I have yet to drop off my shoulder bag when the piercingly loud alarms announce the arrival of a person in "respiratory distress." I run around the ER in search of surgical masks, gowns, and sanitizers, while dodging nurses in the crowded hallways who are scrambling to grab the last remaining oxygen tanks and ventilators. Everything is empty. On my way to EMS triage, multiple nurses pull me to get my attention for their critical patients. We are frantically juggling fiery embers of illness before they turn into a blaze, but I have to get to the inferno that awaits me. An elderly lady struggling to breathe presents with dangerously low blood oxygen saturation. She is too gravely ill to provide any resuscitative wishes. I desperately try to identify her next of kin while the nurses sprint to find a room for her. All the while, the alarm for respiratory distress goes off again and again. Less than five minutes into a disaster of a shift, I mutter to myself: "This is armageddon."

Minutes later, I learn that her daughter is nervously waiting in the lobby. My first words are "your mother is critically ill and I need to know immediately if she would want CPR or to be on placed on a ventilator." The urgency in my voice causes her to cry instantly. Distraught, she asks "do you know long she would be on the ventilator or if it will help?" I didn't know. She mutters, "I don't think she would want this." While she was still processing the news, I am forced back to the ER to put out more fires. Increasing a patient's oxygen in one room. Up-titrating medications in another. Urgently paging my intensive care consultants.

The urgency in my voice causes her to cry instantly

Thirty minutes later, I remember I haven't updated the daughter. I feel like a monster for leaving her outside in tears anxiously waiting for any news. I apologize, offer tissues and water, but am still disgusted with myself that I couldn't counsel her. She requests to hold her mother's hand, but the best I can do is let her wait outside the room. She breaks down sobbing. The nursing home hasn't let her see her mother for the past month, she says. I am heartbroken. I want to ease her grief, but I can't even hug her due to risk of exposure. The nurses need me again to assess other critical patients. I have to go do my job, but I can't shake the feeling that I am not fulfilling my duty to my patient's daughter. I feel helpless. I chose emergency medicine to save lives and comfort people in times of need. Am I failing as a doctor and more importantly as a human being?

I realize what makes the ER a war zone isn't the chaotic environment, the inadequate protection, or the incessant alarms that feel like bombs, but rather the mental and emotional battles we are facing every moment.

2. "Don't be a hero"

It's an unusually cold Tuesday in late March. On my way to the ER, I notice people staring in apprehension. To most, my hospital scrubs mark me as a mobile COVID-19 infection risk.

Is it just a matter of time before I succumb to this virus too?

My patients today include a nurse, FDNY firefighter, and a young asthmatic paramedic. All three are young, previously healthy, and now very sick. Tragically, the twenty-nine-year-old paramedic dies. Shocked, I step outside the ER for a second. My medical school friend happens to call me to tell me that a former classmate a year below us has also died. After a long pause, I tell him I will call back. I need time to process the news. But just moments later, I learn that one of my closest friends, a doctor, has also been hospitalized, and then I discover that a close co-worker, a nurse, has died. Is it just a matter of time before I succumb to this virus too?

I have ten missed calls from my mother. When I finally return her call, she peppers me with questions, and I find myself on the defensive. She asks, "Son, are you ok?" There is a level of fear and panic in her voice I have never heard before. "The news said the cases and deaths are rising! Do you have the proper protective gear? Can you ask for days off? You make essentially minimum wage! How much more are you going to sacrifice, your life?"

Who knew the phrase "I am an ER doctor in New York" would draw such fear and sympathy

I then have a flashback about my journey to get this far—nearly ten years of higher education, relying on food stamps while serving in AmeriCorps, and now nearly $400,000 in student debt. Who knew the phrase "I am an ER doctor in New York" would draw such fear and sympathy. I try to lighten the mood, telling her I'm the latest brand of city superhero—like Batman in scrubs. In public, when people aren't avoiding me for fear I carry the coronavirus, they are clapping and cheering for me as I walk to and from work. That's what I tell my mother—I am a symbol of hope and strength for the entire community. She responds angrily: "Stop! I just want you safe! Don't you dare be a hero!" In the end, I hold back more than I say. If I tell her how much of an emotional wreck I am, her fear for my well-being would grow exponentially. I can't bear the burden of my family's emotional distress on top of my own, so I bottle up my feelings.

3. A Day Off

A day off. I can finally breathe normally instead of gasping through those uncomfortable N95 masks. I slept more than ten hours, but I am still mentally drained. Images of my colleagues on the front line becoming ill are burned in my brain. I recently intubated a patient who was found to be COVID-19 positive. I am at even greater risk of exposure.

Now I am afraid of being quarantined and forcing others to cover my shifts when we're already short staffed. My heart is racing. What if one of my colleagues catches it and then exposes one of their loved ones? The guilt of being at home and worrying about who will be exposed next is suffocating. The gym is usually my outlet to clear my mind, but I don't even have that. It's crazy to think that the ER is the only place I feel sane now. Is this how our military veterans feel during war? Will I ever recover mentally? Will the survivor's remorse last forever? Will I continue to have flashbacks of people losing their lives?

4. The Underserved

A soft-spoken Dominican man kindly asks, "Doctor, I have waited hours. Do you know how much longer? It's getting harder for me to breathe." I apologize to him because I know that other COVID-19 patients need more urgent attention. Unfortunately, we don't have enough equipment, protective gear, and most importantly, staff.

Doctor, I have waited hours. Do you know how much longer? It's getting harder for me to breathe.

The oxygen machine measures him at 94 percent, but drops down to 90 percent with exertion. I offer him an oxygen machine to take home, but he begins to cry and pleads with me in fear. "I lost my job. Now two other families live with me in a one-bedroom apartment in order to save rent money and we don't have any masks," he says. "I fear getting my wife and six-month old daughter sick. Please keep me in the hospital." There's nothing I can do. I am powerless because the hospital has limited beds. I hand him the few remaining masks I could find, but know it won't ease his fear. I feel terrible and guilty sending him home, but he reluctantly agrees and asks if he could just get a sandwich before leaving. Usually, I am too distracted with pressing needs to provide food for my patients, but I am happy to do this one decent thing. As I grab the sandwich, I realize that if he is out of a job, infected, and living with multiple families, how could he provide food for them? I hand him five boxes of cold turkey sandwiches instead. He tears up in joy and thanks me as if I have handed him a week's worth of food. That is probably the most heroic thing I did today.

5. Past the Boundaries

COVID-19 has been a life-altering experience. No amount of schooling or training could have prepared us for the psychological toll of this pandemic. A few days ago, I cried so much for a loved one fighting for his life that I began to question how much fluid our tear ducts can make. We each cope with the trauma in our own way. My own attending physician and a recently minted twenty-three-year-old emergency medical technician both reached their emotional breaking points and tragically took their own lives.

6. A Cry for Help

I hope that my experiences help raise mental health awareness within the health care community. We've seen the physical symptoms of COVID-19 and are now beginning to see the too often ignored emotional and mental impact.

The cost of this pandemic is much larger than the death toll. We may be honored as heroes for our sacrifices, but we don't possess superpowers that shield us from distress. We are no more immune to mental and emotional suffering than we are to the virus.