Discovering the origins of an emerging infectious disease outbreak is a quintessential scientific question—or under normal circumstances, that's how it should be. With the COVID-19 pandemic, nothing seems normal. So what should have been a routine scientific question calling for an objective investigation and an evidence-based conclusion has instead become highly politicized theater on the international stage.

Highly politicized theater on the international stage

History has at least one modern example of a highly politicized debate over infections—during the Korean War, when allegations of biological warfare led to an international investigation in 1952—but there are far more examples of the opposite. China, for instance, never disputed that it was the point of origin of the 1957 Asian Flu pandemic, the 1968 Hong Kong Flu pandemic, the 2002–2004 SARS epidemic and the 2013 H7N9 influenza outbreak. It also has shown no interest in challenging hypotheses that China was the starting point of the 1918 Spanish Flu or the fourteenth century Bubonic Plague.

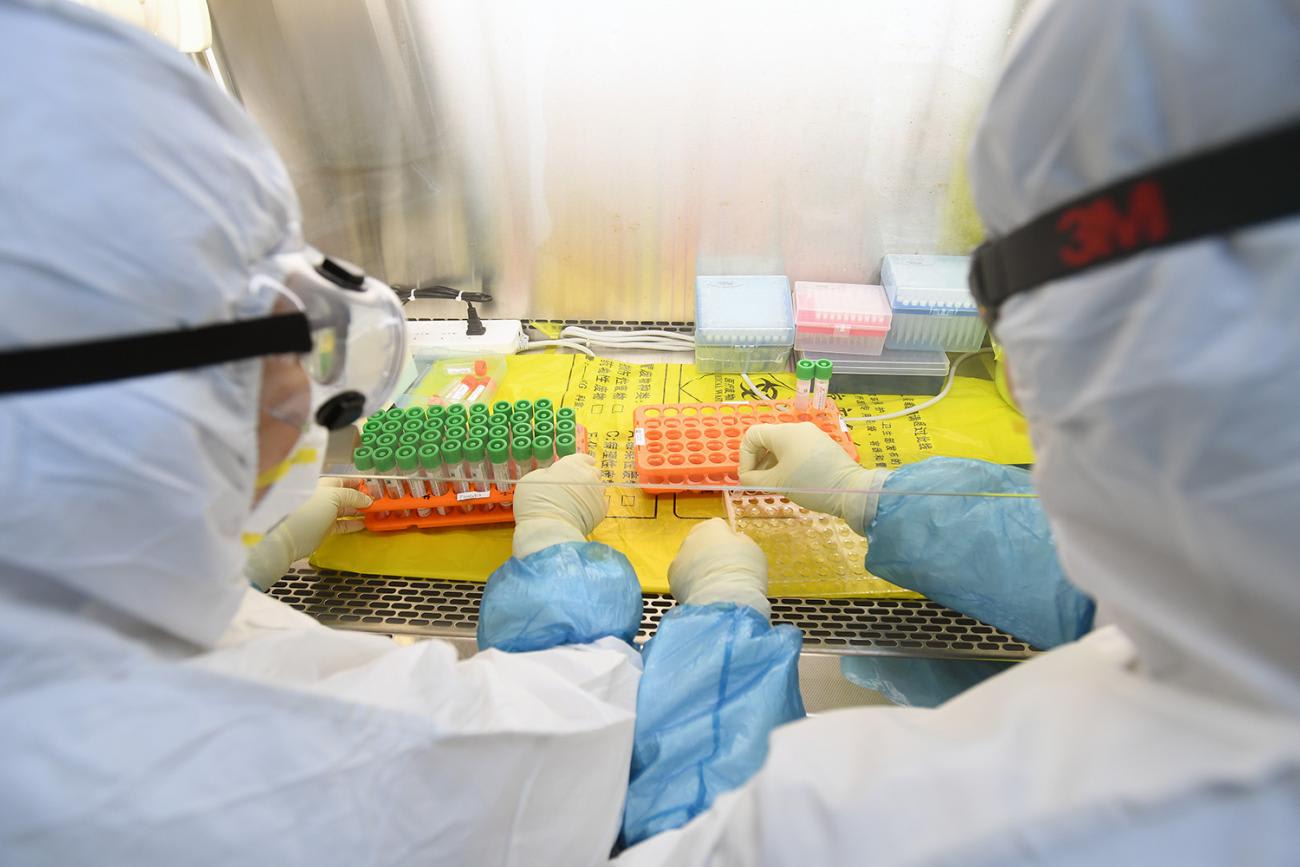

Until late February, China seemed to acquiesce to being the country of origin of the COVID-19 outbreak. Huanan Seafood Market in the city of Wuhan was officially identified as a possible starting point of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Chinese and international scientists also overwhelmingly hold the view that this emerging infection is a naturally occurring outbreak with an animal origin. Overall, despite criticisms of China's mishandling of the early stage of the outbreak, international views of China were not significantly changed by the fact that the outbreak started in China. Few people challenged use of the term "Wuhan virus."

Senator Tom Cotton sent a tweet that made the connection between the virus and a lab in Wuhan on January 30

Beginning in the end of January, conspiracy theories began to surface that the virus was either made as a biological weapon or was allowed to escape from a government lab in China. On January 30, Senator Tom Cotton sent a tweet that made the connection between the virus and a biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory in Wuhan. The next day, a paper authored by Indian scientists and posted on the preprint website bioRxiv implied that the virus might be genetically engineered. Cui Tiankai, Chinese ambassador to the United States, called these allegations "absolutely crazy" and warned that they could stir up racial discrimination and xenophobia. But in early February, similar conspiracy theory suggesting the virus had a U.S. origin and was deliberately weaponized by the United States began to surface in China's social media, the sources of news for most Chinese. Such conspiracy theories, though, remained marginalized and were not endorsed by any leading intellectuals or government officials in China.

On February 17, Zhong Nanshan, the public face of China's COVID-19 containment effort, dropped a bombshell at a government-sponsored press conference by stating that "given the new developments overseas, the disease that was first detected in China does not mean that it originated in China." Zhong did not provide any evidence to substantiate that argument. Neither did he specify what the new developments were.

[The fact that] the disease was first detected in China does not mean that it originated in China

Zhong Nanshan on February 17

According to the WHO situation report released the same day, in almost every country with confirmed cases, a certain number of the cases had travel history to China. Only days later, his claim was echoed by a paper authored by Chinese scientists and posted on the preprint website ChinaXiv, a Chinese copycat version of bioRxiv. The paper challenged the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 originated in Huanan Seafood Market, and suggested that the virus found in the market "should be imported from other places." On February 23, a report from a Japanese TV station suggested that SARS-CoV-2 could have originated in the United States, where some of the 14,000 people killed by influenza might have contracted the novel coronavirus. Zhong's claim, however, was dismissed by Zhang Wenhong, a leading infectious disease expert in China who is well known for his straightforwardness and honesty. But the section of the story containing Zhang's comments that he did not believe the virus originated anywhere other than Wuhan later vanished from the government newspaper China Daily, which published the exclusive interview on February 28. Few at the time recognized that Zhong's claim of a non-Chinese source would soon become China's official narrative on the origin of the outbreak.

In tandem with Zhong's remarks, late February saw the rise of rumors and conspiracy theories in China's social media. A widely circulated screenshot, for example, claimed that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed that the first coronavirus cases came from the United States.

CDC confirms first coronavirus case of "unknown" origin in U.S.

CNN headline that gave rise to conspiracy theories

However, the February 27 CNN headline—from which the statement was translated—was "CDC confirms first coronavirus case of 'unknown' origin in U.S." Most of the conspiracy theories that have resulted since have drawn on information recycled through old news, publications, and grey literature. Some linked the outbreak to rising pneumonia cases in the United States, which were suspected to be associated with vaping. There were some based on findings in publications like the ChinaXiv article. Still others implied that the outbreak might be related to foreign soldiers who were sick during the Military World Games held in Wuhan in October. Still, government newspapers and major Chinese internet platforms, including Tencent and Netease continued to publish articles and interviews to dispel such rumors or conspiracy theories, indicating that blaming the United States as the origin of the outbreak was not the dominant propaganda theme at that time.

As the Pandemic Heated Up, So Did the Rhetoric

By early March, the disease was close to being stabilized in China, while the U.S. began to see its number of cases surging. The contrasting trajectory of virus spread provided a great opportunity for the Chinese Communist Party to systematically push the narrative of the authoritarian state's superiority over liberal democracy, a campaign launched around the end of 2019 but disrupted by the outbreak.

A narrative intertwined with the government's initial mishandling of the outbreak

There was only one problem at the time: the government's narrative would be neither coherent nor convincing so long as China was still perceived as the origin of the outbreak, a narrative, after all, which was intertwined with the government's initial mishandling of the outbreak. So beginning in March, China's social media became inundated by posts and essays that point to the United States as the origin of the outbreak. The overwhelming prevalence and popularity of such claims—many of which were as preposterous as contending that the 9/11 attacks were orchestrated by the U.S. government—was unusual in a country where police are very efficient in discovering and disciplining rumormongers and censors typically remove online posts that are not aligned with official party lines. State media also joined the anti-American chorus by publishing essays or producing headlines that disputed China's role in unleashing the virus. On March 4, a foreign ministry spokesperson cited Zhong Nanshan's comments to contend that China was never proven to be the origin of the outbreak.

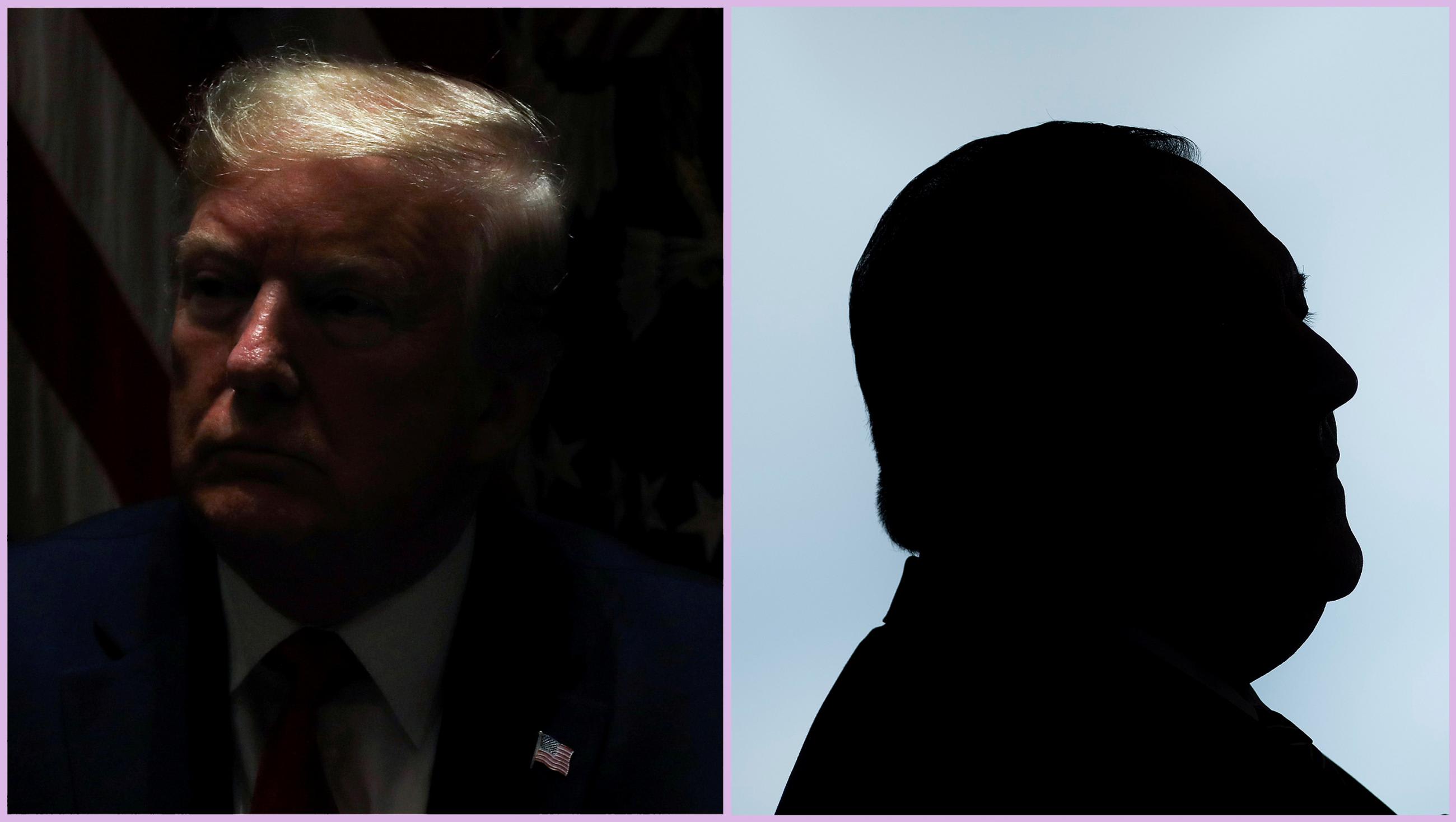

In the meantime, a parallel politicization of the virus' origins was happening in the United States. Top U.S. diplomats and allies of President Donald J. Trump increasingly linked the virus to China. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, for example, repeatedly and deliberately used "Wuhan" to describe the virus, even though the WHO officially named the disease caused by the virus COVID-19 on Feb. 11. According to the Washington Post, he did that in part to respond to Chinese misinformation efforts.

A Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson tweeted the conspiracy theory that the U.S. Army imported the virus into Wuhan

Pompeo's response triggered stronger reactions from China, which condemned his use of Wuhan in naming the virus a "despicable practice." The blame game was played out at a whole new level when a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson tweeted on March 13 to publicly promote the conspiracy theory that the U.S. Army might have spread the virus in Wuhan. He also implied that the outbreak was caused by a biosafety accident in U.S. Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) in Maryland, which resulted in the shutdown of the lab in August 2019. President Trump responded by doubling down on the efforts to point fingers at China. Where previously he was referring to SARS-CoV-2 as a "foreign virus," the president began ramping up the narrative by now routinely referring to it as the "Chinese virus," as he did in a tweet posted on March 16. Three days later, he was found to have crossed out "Corona" from the phrase "Coronavirus" in his notes prepared for his March 19 press briefing and replace it with "Chinese."

President Trump's frequent and deliberate usage of the term was widely criticized as being racist and xenophobic in both the U.S. and Chinese press, but it also triggered a nationalist backlash in China that solidified support of the official narrative exonerating China from any wrongdoing in the outbreak.

Whether or not human beings choose to believe something or pass it on to others depends largely on what they already believe

Cass Sunstein, "On Rumors"

As Cass Sunstein noted in his book On Rumors, whether or not human beings choose to believe something or pass it on to others depends largely on what they already believe. Those who are already convinced that the United States has ulterior motives against China are more likely to accept and spread the rumor of a U.S. origin of the outbreak. That effect is amplified by conformational bias—the tendency of human beings to ignore evidence that contradicts what they think but accept data that supports their preconceived notions. It came as no surprise that Chinese social and state media was awash in the so-called "evidence" that suggests outbreaks elsewhere that were earlier than China's. Under various theories, the United States, Japan, France, Italy, Spain, and Brazil were all suspected of starting the pandemic. "I think 90 percent of those living in the countryside or small cities in China buy the theory that the virus originated in the United States," one Chinese source told me in private. But a significant number of Chinese elites, most of them living in major cities, also fall prey to the conspiracy theories. Many times, even professors at leading Chinese universities or think tanks are thrilled at sharing posts or essays that support China as a non-origin of the outbreak.

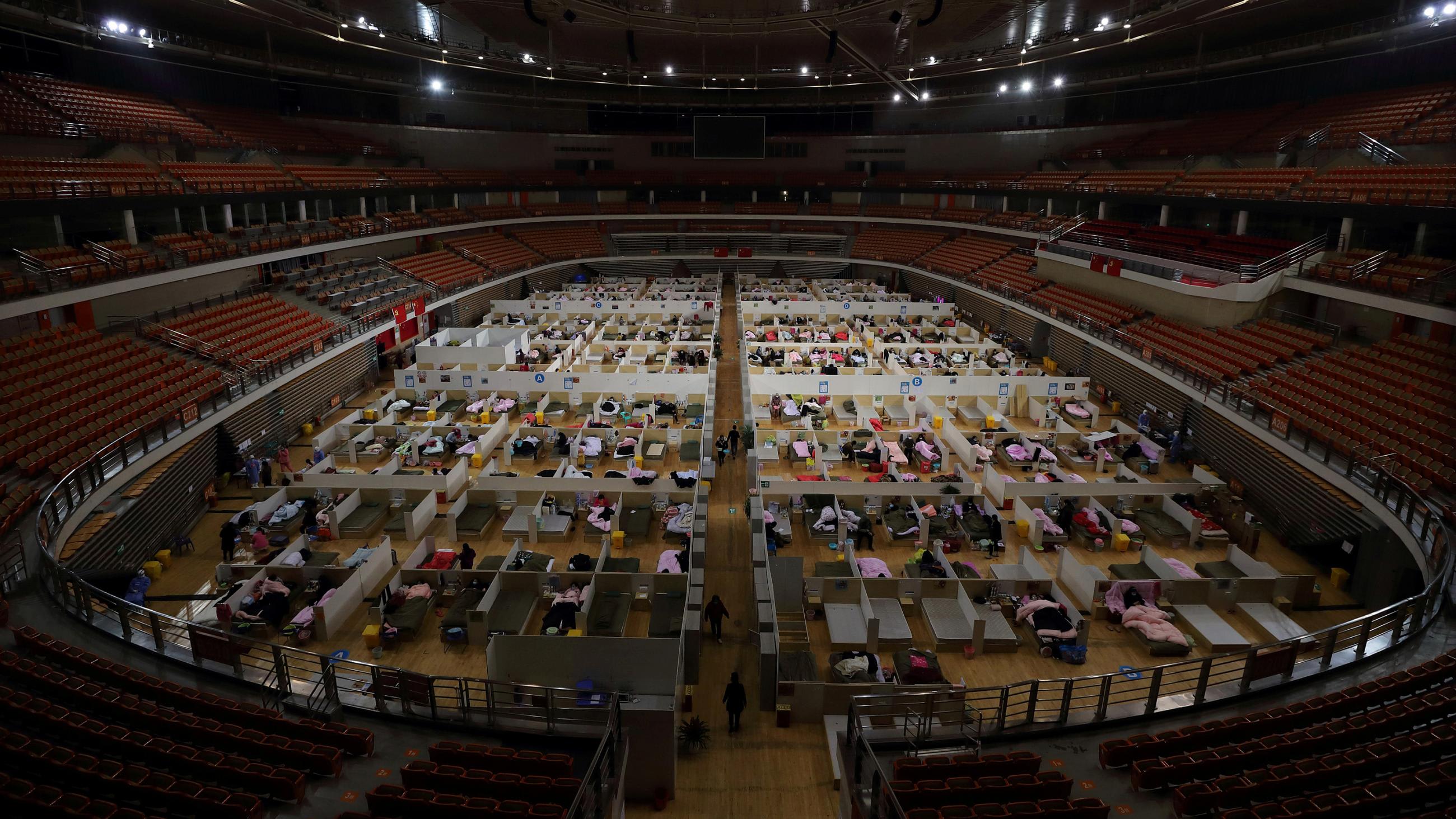

Calls to Hold China Accountable

While the imported-from-outside theory became dominant in China, the rest of the world has maintained that China is the origin of the outbreak. That cognitive gap between China and the international community expanded as China emerged as an early winner in containing the spread of the virus while other countries were still struggling to tame the surge of infections. Beginning in mid-April, there have been growing calls to "hold China accountable" for the outbreak and efforts to seek compensation from China for the human and economic losses incurred by the outbreak. Late that month, Australia became the first country to publicly call for an investigation into the pathogen's origin, despite China's threats of boycotting Australian goods. The proposal soon received support from other countries. On May 19, more than 130 member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) adopted a landmark resolution that requests the director general to work with other organizations and countries "to identify the zoonotic source of the virus and the route of introduction to the human population."

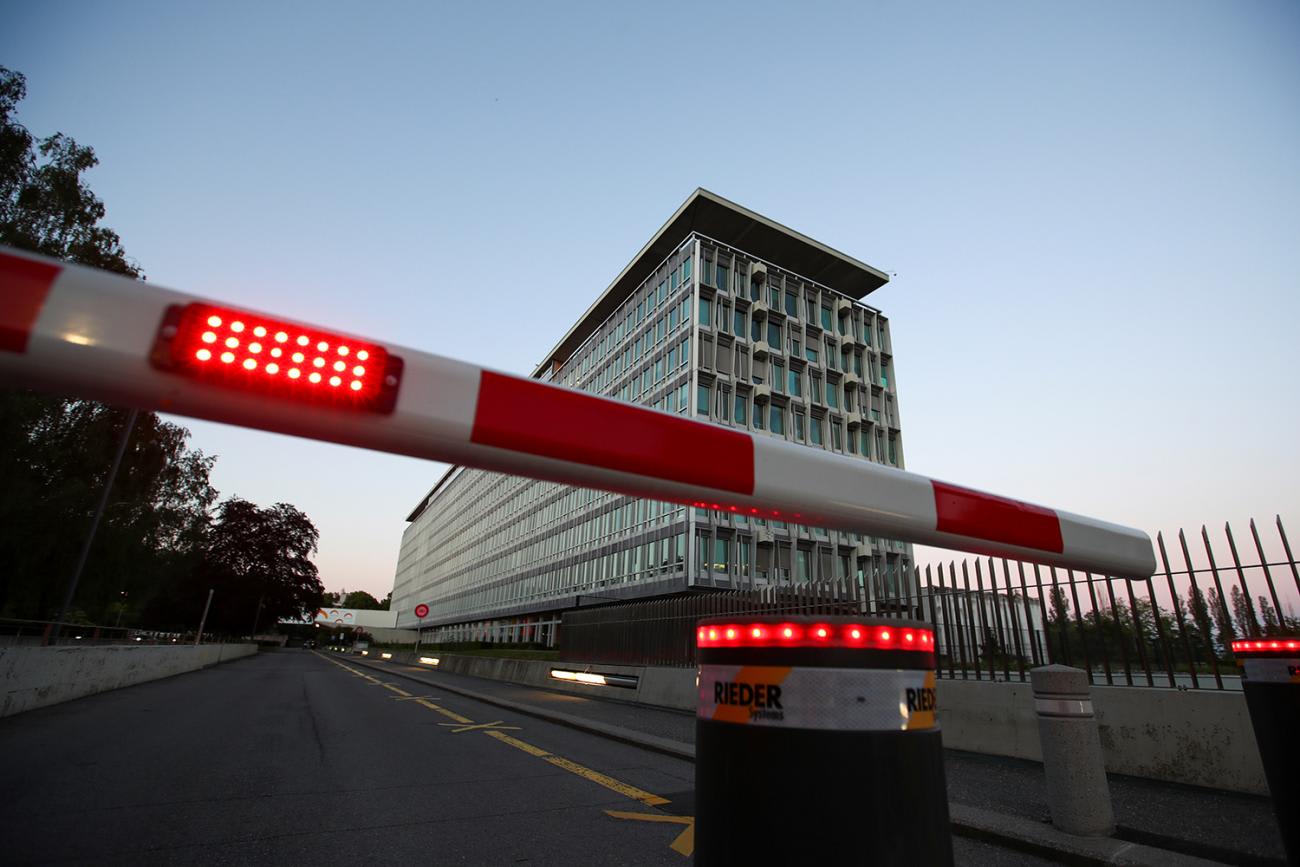

On May 19, the WHO adopted a landmark resolution to identify the zoonotic source of the virus

Amid mounting international pressure, China quietly changed its position over the COVID-19 probe. In early May, the WHO and China were in discussions about investigating the origins of the virus. Despite its initial hesitation, it eventually co-sponsored the May 19 WHO resolution. When speaking at the World Health Assembly, President Xi Jinping expressed China's support of global research on the origin and transmission of the virus, as well as a "comprehensive review" into the global response to the pandemic. This paved the way for sending another WHO investigation team to China. On July 11, the WHO advance team arrived in Beijing.

Beijing did face a policy dilemma over whether and how to host the WHO investigation team. It would tarnish its image as a cooperative and responsible state if it refuses the WHO's request for an investigation. But being identified as the first (and likely the only) country in which to start the investigation strongly signals that China is the most likely candidate for the origin of the outbreak. Not surprisingly, the visit received little coverage in China's social and state media.

The government media reported the visit by verbatim copying the news release of Xinhua News Agency. It highlighted that the issue as "an ongoing process" that may involve multiple countries and places. Clearly, Beijing wants to avoid giving the domestic audience the impression that China is the only country where the probe will be conducted. On August 3, when the advance team ended the trip, it published a short press release that WHO scientists of the team discussed with their Chinese counterparts over "the China component of the global scientific plan of tracing the origin of SARS-CoV-2."

In the meantime, Beijing wielded "sharp power," manipulating information to influence target audiences, to benefit diplomatically from the WHO investigation. The government stressed that it took the initiative of extending the invitation.

China's foreign ministry urged on August 4 that the United States "fully clarify" its "militarization of biological activities overseas."

Chinese diplomats and government media spared no effort to use that opportunity to tout China's "open, responsible and poised" attitude toward the inquiry, while portraying the United States as a country that is neither cooperative nor transparent over this issue. A foreign ministry spokesperson expressed the desire that "all related countries" follow China's example to "adopt proactive attitude in cooperating with the WHO." By making insinuations about the United States, China did not hide its displeasure with Secretary Pompeo's comments on China–WHO cooperation. Misinformation and distraction continued to be pursued to frame the United States as a more likely candidate for the origin of the outbreak. A government newspaper linked the timing of the U.S. decision to withdraw from the WHO to the WHO announcement of dispatching the advance team to China, suggesting that the United States did so to avoid a WHO investigation. Another government-sponsored media outlet echoed the conspiracy theory by questioning the timeline of COVID-19 outbreak in the United States and linking possible vaping-associated diseases and U.S. military labs to the outbreak. In a move that was reminiscent of the Russian insistence that it be allowed to visit U.S. military facilities overseas conducting infectious disease research, China's foreign ministry urged on August 4 that the United States "fully clarify" its "militarization of biological activities overseas."

Doubling Down on the Blame Game

On the U.S. side, beginning in May, the Trump administration began upping the ante by asserting that there was "enormous evidence" that the virus originated in the BSF-4 lab in Wuhan, although those who have looked at intelligence said in private that the evidence was mainly circumstantial. Indeed, even the Australian prime minister, who initiated the call for the international inquiry, said that he had no evidence to support that theory. While the virus is unlikely to be a bioweapons agent, an alternative theory that attributes the outbreak to a virus accidently leaked from a biological lab in the city, remains a legitimate speculation. On July 29, a Wall Street Journal editorial challenged the widely held claim that the virus jumped to humans from animals in the wild or in wet markets, and argued instead that a lab escape is a more plausible explanation. Not surprisingly, Chinese scientists denied such claims.

A Wall Street Journal editorial argues lab escape is more plausible than the virus having jumped to humans from animals

Nearly seven decades ago, China, the Soviet Union and North Korea accused the United States of using germ weapons in the Korean War. U.S. government officials denounced the allegations as a hoax. When the International Red Cross and the WHO ruled out biological warfare, the Chinese government refused to accept the verdict and asked instead the Soviet-affiliated World Peace Council to set up the International Scientific Commission for the Facts Concerning Bacterial Warfare in China and Korea. The commission report confirmed that the U.S. indeed experimented with bioweapons in Korea. In 2016, a report from the Wilson Center concluded that the allegations were "really active fraud and disinformation." This historical episode is illustrative. It shows how difficult it is to conduct a truly independent and impartial investigation when the involved parties cannot even agree on who the jury is.

The WHO investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 outbreak is now sandwiched between China, who is determined not to allow the investigation to undermine its official narrative on the outbreak, and the United States, whose leverage over both the WHO and China is in decline as a result of its withdrawal from the organization and the rapidly deteriorating relationship with China. Already, Secretary Pompeo has said he expected the WHO investigation to be "completely whitewashed."

Simply put, we may never know

In early August, China allowed American journalists to visit the BSL-4 lab in Wuhan. That seemingly symbolic move signaled that future WHO investigation team will have access to the institute, but it also suggests that it would be unrealistic to expect the team to unearth any smoking gun evidence—if it ever even existed—that links the lab to the outbreak. Just imagine how devastating such evidence would be to the Chinese regime. So where did the novel coronavirus come from? In the end, with the origins of COVID-19 having become so politicized in the context of a looming new Cold War, having a truly independent, transparent, and thorough investigation whose findings are accepted by all parties will be a mission impossible. Simply put, we may never know.