Dr. Mary Travis Bassett is known for her leadership of domestic public health institutions, including New York City's Department of Health from 2014-2018 and New York State's health department in 2022. But she spent formative years at the beginning of her career on the medical faculty of the University of Zimbabwe, teaching and working alongside a young cadre of public health practitioners who had returned to rebuild the newly independent nation.

She spoke with Think Global Health about how race shaped her upbringing and her interests, and how her time working in Africa influenced her thinking about public health at home.

□ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □ □

Think Global Health: How central was race to your personal identity growing up?

Mary Bassett: It's been quite a central, for very personal reasons.

I'm mixed race. My mother is a person who is classified as white, and my father is Black. He came from Virginia — he's now deceased — and the state of his birth and his upbringing fought the legal right to marry interracially all the way to the Supreme Court. The laws against interracial marriage weren't overturned until 1967, the Supreme Court decision [known as] Loving.

My father was very committed to having us understand his own background. He was what we would call a "peasant," if we use that word in the United States. His family were farmers, and he was determined that we remained connected to his family. But my parents never traveled there together until after the Loving decision. So in my childhood, I was aware of race from the very beginning.

As a young child, and I don't know quite how old I was, maybe I was ten, I remember being told when we went to town that I should identify one of my father's sisters, one of my aunts, as my mother, if anybody should ask me where my mother was. Because my mother traveled with us, but without my father.

So I just remember, as a child, how anxious I felt that I might do the wrong thing and get my family into trouble. In that sense, race was central to my identity.

The other part of it was my parents were civil rights activists. So I grew up learning about their efforts. My mother would rent apartments for Black families; she went to see whether the apartment was available to her as a white person, and then the black family would go, and it wouldn't be available to them, and then they would have a basis to challenge [it legally]. So I can't think of a time when I wasn't aware of the levels of exclusion that the United States has pursued based on race.

As a child, I felt anxious that I might do the wrong thing and get my family into trouble. In that sense, race was central to my identity

Dr. Mary Bassett

Think Global Health: Do you think it influenced your early academic and professional choices?

Mary Bassett: I decided to become a doctor after I worked as a census taker in Harlem, before I went to college. In those days, the census was conducted with a satchel on your shoulder and long forms and short forms, and you sat with your pencil at people's kitchen tables. And I saw people with what I considered obvious health problems. I was very aware that the community where I was being welcomed to kitchen tables was a Black and Latino community. So it was observing what looked like medical neglect, or lack of access to care, that made me want to become a doctor.

And as a young person, of course, Africa was becoming independent. And I was an avid supporter of African liberation struggles —to which by the way, the United States never contributed a single penny to—and I guess that was how I came to be interested in and work in Africa.

Think Global Health: What were the circumstances that took you to Zimbabwe?

Mary Bassett: I went to Zimbabwe after I'd finished all of my training. In the United States, training to become a medical doctor is interminable: first you go to college, then you go to medical school, then you do hospital training, and in my case, I did a chief residency, and then I did a fellowship. So, at the end of all that, I really wanted to change up my life. And I was ending a marriage. But I also felt that I was being channeled into a neighborhood of doctors and lawyers, and I wanted something more interesting than that.

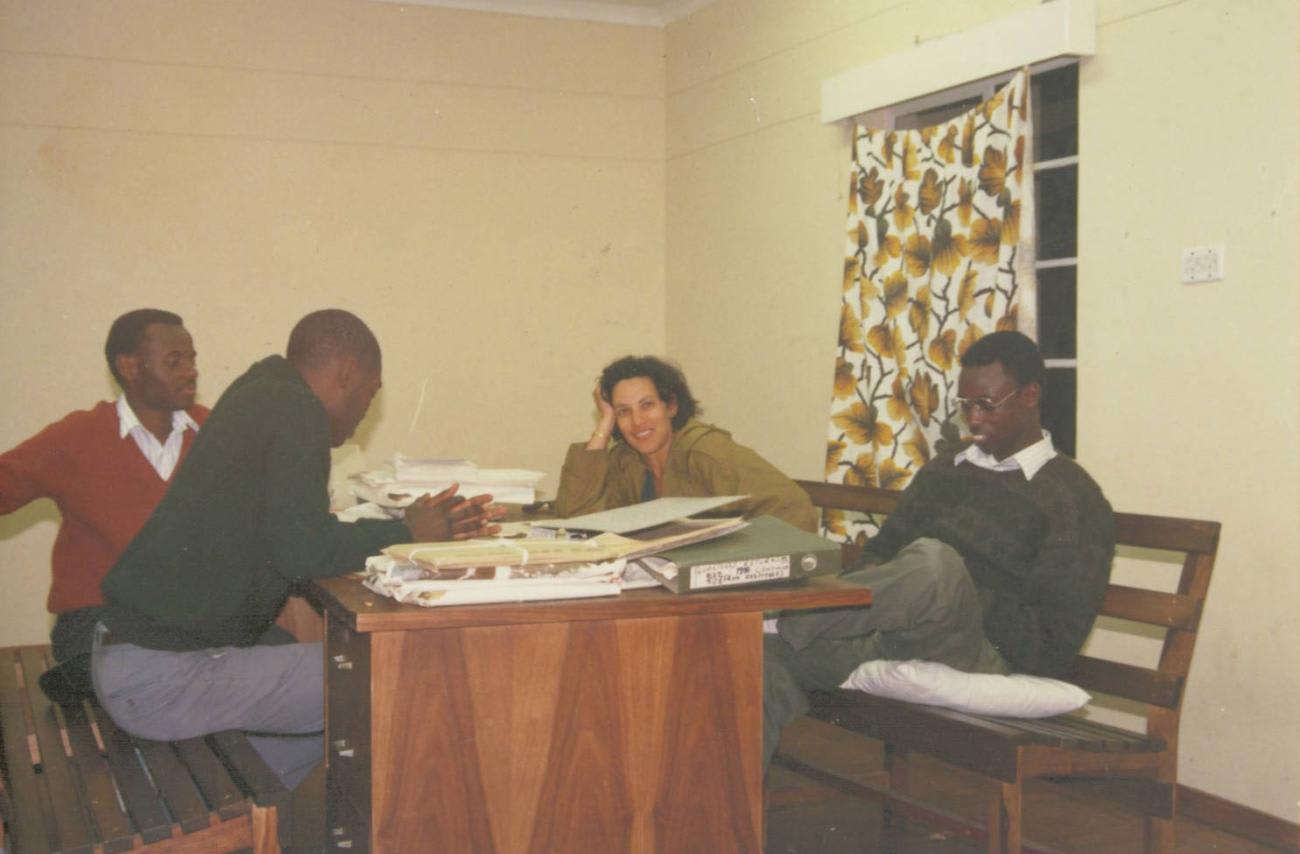

I had a friend whose parents were working at the University of Zimbabwe—they joined the faculty immediately after independence, when Zimbabwe called for people to come help—so, I applied for a posted job, and much to my surprise, I was offered a post as a lecturer. I thought I would go for two or three years and come back — I had a good job lined up at a very well-respected university—but when I got to Zimbabwe, I was swept up by things. I ended up staying there nearly twenty years.

Think Global Health: Could you expand a little on how you got swept up?

Mary Bassett: For a period of time, Zimbabwe had one of the highest performing health systems in Africa.

It had been a settler colony. Like South Africa, the white population built a country for themselves, a fine university, fine government-funded schools. It was, in a way, a kind of socialism for white people. Because the public sector that was designed to serve the white population was really outstanding, but it was not meant for the Black population, which was by far the majority.

[The liberation struggle, by which it attained independence in 1980], was very bitter — the estimates were that 20,000 people lost their lives. But [the country] had a lot of assets that were now available to the Black majority. At the same time, it was determined to serve a far larger sector of the population than these assets had been designed to serve.

It really embraced the notion of primary health care, as articulated in the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration (which, by the way, I had public health training but had never heard of when I went). It had embraced the notion of village community workers. And the Ministry of Health was staffed mainly by Zimbabweans who'd returned to the country with advanced training. So it was just an incredibly exciting time, because they were determined to meet the health needs of the nation themselves.

And the university was not an ivory tower — it was a country that couldn't afford an ivory tower — so we were in the process of retooling the curriculum so that the medical students were exposed to rural health care. The department that I was in was focused on building an urban component that focused on clinics and what I would describe as townships. I felt very privileged to have been accepted and been part of it.

Think Global Health: You used the word "privilege," and obviously, there are layers of power when there's nationality, race, class…

Mary Bassett: Gender.

Think Global Health: How do you think your experience there was affected by those things—both what you saw and how you were seen?

Mary Bassett: People did not consider me Black. If anything, they considered me colored. But I was American, mainly. You and I know it's not, but to the world the United States is a white nation, and I was considered American. So that's why I say I was privileged. As an individual, I was accorded membership on the team, so to speak.

Think Global Health: Was that nice?

Mary Bassett: It was great, [for a time]. Then, of course, Zimbabwe was forced to adopt austerity measures, called a structural adjustment program. And things didn't go well for Zimbabwe, and they're certainly not going well now.

Think Global Health: Since you grew up with an acute sense of power and race, do you think that affected how you observed things in Zimbabwe, compared to white Americans who were there?

Mary Bassett: I would think so. The Ministry of Health took the "best" people so the university sort of [got what was] left. When I arrived there were still a lot of people who would have called themselves Rhodesian. I remember somebody pulled me aside and said, "Our students are barely out of the Stone Age. Just be aware of the kind of standards that you apply to these students." It was so racist. And I have to say that I've [since] taught in a number of different settings, and I never encountered stronger students than the ones at the University of Zimbabwe.

Think Global Health: You spent nearly a quarter of your life there. What are the deepest ways that influenced you?

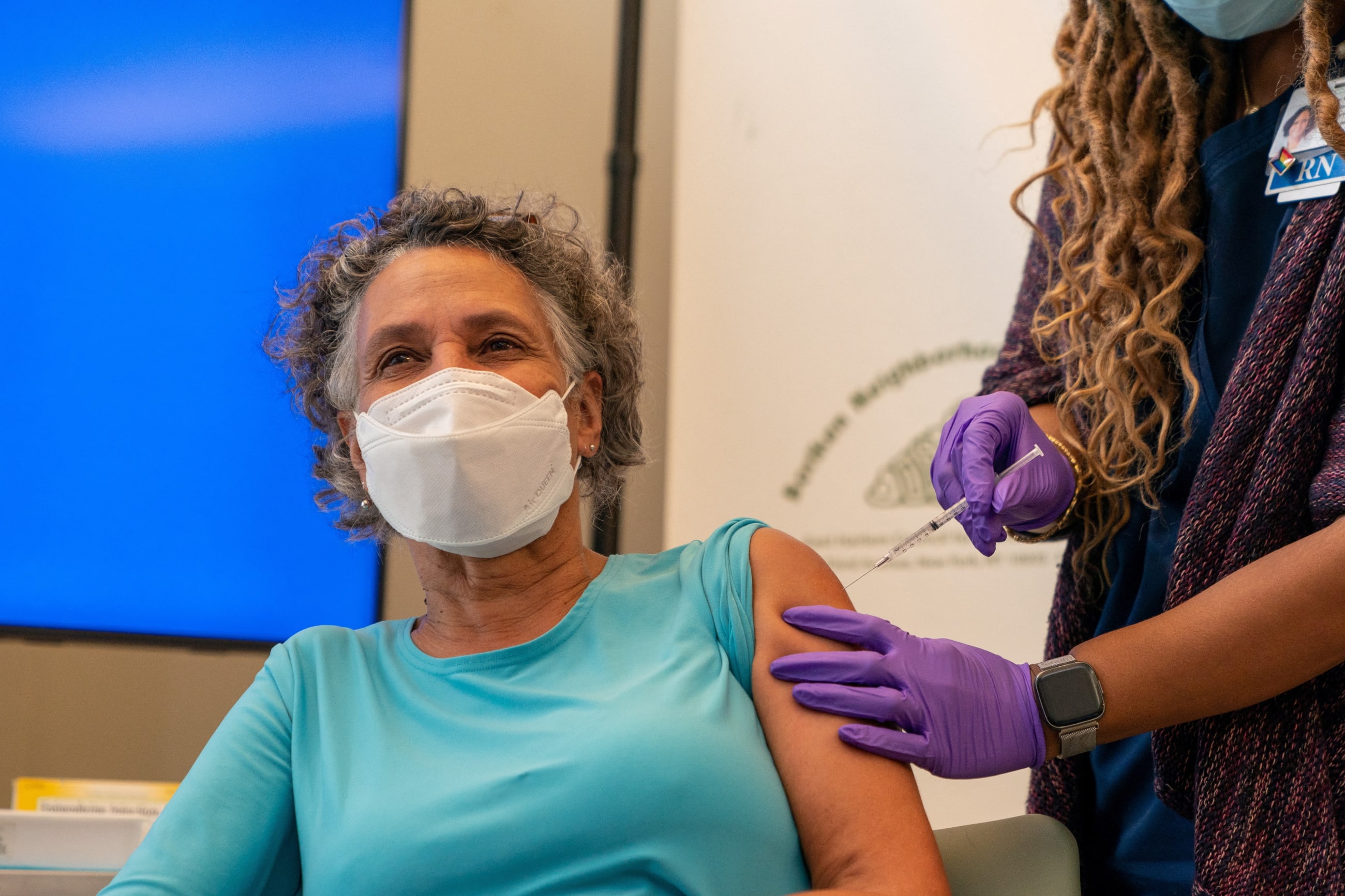

Mary Bassett: The Ministry of Health had halved the infant mortality rate, had greatly reduced the impact of diarrheal diseases, mainly by promoting home treatment with sugar-salt solution. There were huge increases in the proportion of children who were fully immunized. The government, with donor support, expanded clinics, built rural hospitals, really prioritized health.

So I guess the biggest lesson for me is how quickly we can advance health when you have a government that's committed. There are a lot of lessons there for our own country, where public health has certainly not been accorded that kind of prioritization. And, as the decline in Zimbabwe has shown, those advancements are often fragile.

Also, there are wonderful African institutions that should get our support. I watched with great happiness the advent of programs like PEPFAR, which brought effective AIDS treatment to Africa, but was disappointed that more of it wasn't used to strengthen national institutions.

A man in Bangladesh was more likely to live to the age of 65 than a man in Central Harlem

Think Global Health: Do you think that link you felt strongly between America and Africa is the same still today for African American youth?

Mary Bassett: I don't know. Do you remember the image of the people at the Olympics with their fists in the air? African Americans had a global reputation for the Black freedom fight. So that that was part of it. And then it was reciprocated with an interest in Africa. I don't know whether it still is there now.

Think Global Health: Naming racism and advancing equity have been a through-line in your academic work. Was that there from the beginning?

Mary Bassett: I trained at Harlem Hospital, where the people were the sickest I've ever seen anywhere. So it certainly was part of my thinking then. There was a paper that showed that a man in Bangladesh was more likely to live to the age of 65 than a man in Central Harlem. And the man who wrote that paper, Colin McCord, worked in Mozambique for many years, which is where I first met him.

When I first went to Zimbabwe, about half of our medical students were white. Over time, everybody was Black. So it became more issues around class, to be frank, about showing support for students who came from rural backgrounds.

But I don't know a place where race doesn't play a role. It's not the only division in our world, but the ideology of white supremacy underlay the whole colonial project. It had a role in Asia and in Africa. And of course, it was a principal justification for the enslavement of Africans in the Americas.

I've encountered, many times in my working life, people who think that I'm over-focused on racism. Certainly, in our public discourse in the United States, this has become a flashpoint. But the fact is that it's a card that's in the deck. It's there. These are facts. And it would be shocking if they didn't influence our lives and our bodies and our health.

Think Global Health: You came back to United States. Did you ever feel like you had to tap back into things that were here?

Mary Bassett: It's not common for Americans to live outside of the country for many years. I felt very lucky that I was able to move into positions of authority and responsibility.

I went first to work for the New York City Health Department and it was a big change. I was really struck that nobody was talking about race anymore. They didn't even use the word. People would say things to me like "we have a 'diverse candidate' for you." What the hell does that mean? What they meant is somebody who wasn't white, and the language had changed. Nobody ever talked about racism. And when I became commissioner in New York City, there was not a single Black or Latino on the leadership. This is in a city that is more than half Black and Latino. A commitment to excellence cross-walked with whiteness.

Think Global Health: Things changed during your tenure there.

Mary Bassett: I had a majority non-white leadership team for the first time in the history of the Health Department.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This interview was conducted via Zoom and has been edited for length and clarity.