The Netflix miniseries Adolescence has sparked a global dialogue on toxic masculinity, media, and violence. The series depicts the arrest of a 13-year-old Brit named Jamie, who is accused of murdering a teenage girl named Katie after being influenced by violent and misogynistic social media. The series has had record-breaking success, garnering more than 120 million views only a month after its release. Reviews have called it the "wake up call we've been waiting for" and a series that every parent "needs to watch."

Adolescence fits on a spectrum of products from social impact entertainment to social behavior change initiatives, including edutainment. Despite differing definitions of the term, at its core, edutainment combines entertaining storytelling with educational messages. Edutainment is often evidence based in an effort to raise awareness, change attitudes, norms, and behaviors by modeling good or bad behaviors that start a social debate on previously overlooked issues. Edutainment is not new, but with growing digital connectivity it has become an increasingly popular form of promoting prosocial messages on challenging and sensitive topics such as violence.

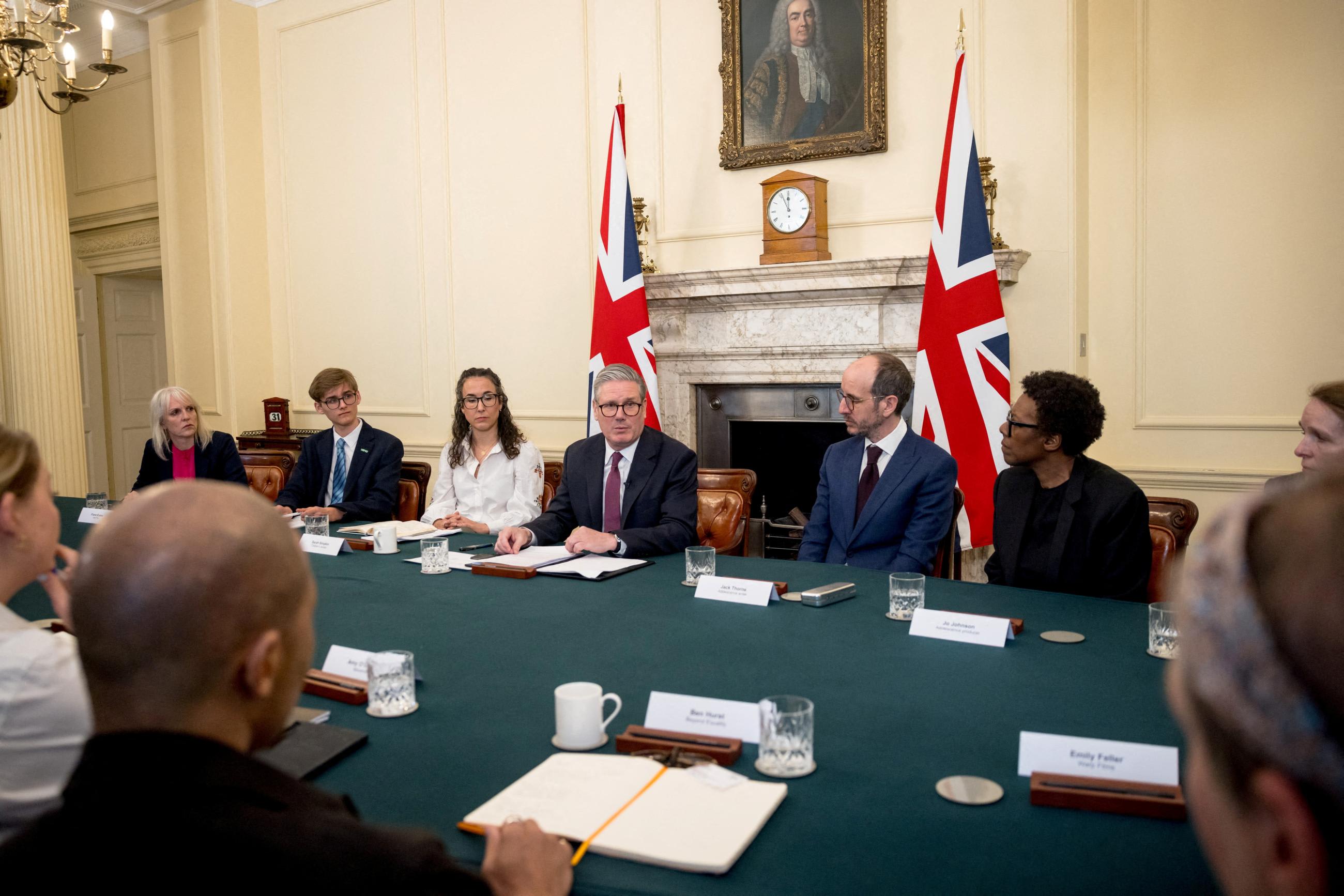

Why is there so much buzz about edutainment? The appeal lies not only in the captivating storylines, but also in the potential for scale. Edutainment can reach millions of viewers at a substantially lower cost than traditional social behavior change efforts. Adolescence conveys this phenomenon by placing issues such as the manosphere (an umbrella term for online communities that promote misogynistic views) within the public and policy discourse—more quickly and more effectively than years of research and advocacy had been able to. The UK government has swiftly responded with conversations and steps to rethink adolescent safety online and in the classroom.

Edutainment can reach millions of viewers at a substantially lower cost than traditional social behavior change efforts

Will "all the talk" translate into real change? A review of rigorous evidence, published in April in the World Bank Research Observer, suggests that the answer is yes.

The review looked at causal evidence on diverse forms of edutainment and how it was able to change attitudes, norms, and behaviors related to violence against women and children in low- or middle-income country settings. Looking across 21 rigorous studies, researchers found that overall 71% showed reductions in attitudes and norms supporting violence and that in 11 of the studies 64% showed reductions in violent behaviors.

How does edutainment influence behavioral change? The review identified four main channels, depending on the context and topic. First, edutainment provides an information channel that enables participants to share beliefs and learn about violence topics, such as laws and punishment for perpetrators.

Second, participants could be influenced by an individual persuasion channel through exposure to role models and portrayals of different behaviors that were previously unseen or underappreciated. For example, the portrayal of a strong male character could promote freedom from violence and a loving, gender-equal relationship that may garner interest and appreciation from other men.

Third, edutainment has potential to trigger a norm diffusion channel, in that participants could believe that others in their social networks or communities are simultaneously changing their stance on the same beliefs. For example, a radio show might socialize a new norm that child marriage should be avoided, thereby weakening the social pressure people may feel to conform or comply with the harmful behavior.

Finally, a service linkages channel could promote behavioral change by encouraging individuals to seek survivor services, legal mediation, or law enforcement.

The evidence from these studies was most robust for violence against women and child marriage themes. For example, in rural Uganda, women reported a 25% reduction in experiences of violence eight months after communities were exposed to three video clips depicting self-contained stories of violence survivors. In Vietnam, young men reported lower rates of perpetrating sexually violent behavior for up to one year after participating in a web-based online training titled Global Consent, which included three hours of a serial drama.

Fewer studies were found on female genital mutilation; however, promising initial evidence suggests changes in attitudes supporting uncut girls, including in a study of a feature-length movie in Sudan and a television series in Senegal. Nonetheless, only one study examining a local radio show and drama in Tanzania was identified as measuring behavioral impacts on violence against children. This study found limited effects on both attitudes toward violence and adult use of punishment of children in the household, possibly because of caregivers' limited exposure to the show, indicating a role for further research and testing.

Although this academic progress is encouraging, considerable creative innovation and testing remains for edutainment related to violence and toxic masculinity. Much is still unclear about the design of such media products and their operational features: How intensive or sustained should content and messaging be to sustain impacts? How do we balance the need to develop locally relevant narratives with the desire for at-scale, population-level impacts? What complementary programming, including community engagement and mobilization, is needed to guide narratives or maximize impacts? Which strategies can promote engagement of hard-to-reach groups, such as men and boys, who could be more difficult to attract and captivate with gender and violence themes?

The good news is the edutainment engine is gaining traction and offering numerous opportunities for innovation. Recognizing the power of edutainment for social change, UNICEF has increasingly invested in diverse products that address hard-to-tackle issues. For example, a recently released television series in Egypt, Lam Shamseya, boldly calls attention to child abuse within a "gripping storyline" of a woman named Nelly who discovers that her stepson has faced sexual harassment perpetrated by his father's best friend. The miniseries Vaillante, set in a fictional West African country, explores child marriage and how girls can take back power to seek an end to the practice through the eyes of a young activist, Sadi, whose life intertwines with a 14-year-old and soon-to-be-married girl named Adi. In Lebanon, the Qudwa (role model) initiative is positioned as a key pillar of the government plan to protect women and children from violence and harmful practices, using diverse edutainment and community mobilization tools, including television series, community theater, comic books, and outdoor cinema. The radio soap opera Ouro Negro, tackling diverse forms of violence, has been running for a decade in Mozambique—reaching up to 4 million listeners per episode.

UNICEF's model recognizes that edutainment is only one tool of a social behavior change approach and promotes guided and reflective dialogue through community engagement and mobilization to empower local action toward better societies.

The arts have been used for centuries to raise awareness and inspire social change. Emerging evidence about how edutainment strategies influence behavior can improve their potential to address even more complex and entrenched issues such as misogyny and violence. Looking ahead, edutainment offers ample opportunities for collaboration between artists and scientists: from traditional forms of media to newer innovative models, including video games, virtual reality and social media–driven products.

The private sector has immense potential to produce shows that simultaneously entertain and contribute to a better world. Director Philip Barantini said the Adolescence series was meant to "spark a bit of a conversation" around acts of violence perpetrated by young boys and men in the United Kingdom—but who could have foreseen that it would unleash a global debate? Paired with rigorous evidence in hand, this outcome is promising for future efforts—to be grounded in research and designed with careful intentionality around behavioral change.

After all, as Stephen Graham, actor and writer of the series, emphasized, "we are all slightly accountable in some way, shape or form" for raising a child.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: Views are the author's and do not represent the views of UNICEF. Financial support for the evidence review "Edutainment to prevent violence against women and children" published in the World Bank Research Observer was provided by the Prevention Collaborative, a feminist-inspired network to prevent violence against women and children.