I stood in my driveway as the sun began to set on the outskirts of Lusaka, leaning on my vehicle after a long day, my phone pressed to my ear. The donor executive on the other end was repeating herself. I had asked for clarity. "We have decided to rescind the grant," she said for a second time. "The funding is being withdrawn." I had just moved from my position as Chief Medical Officer for the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) during the Obama administration and taken over as CEO of large Zambian NGO supporting hundreds of thousands of people with HIV and providing other health services. Losing a major funder was hardly the start I'd imagined.

The novel coronavirus pandemic has raised the stakes for all of us, and has made the local capacity to deliver health care all the more critical

Yet the events that followed this call were the key to unlocking the progress I hoped to make for the organization and the health of those we served. In order to improve oversight, we initiated a top to bottom review of our financial controls, management, and governance, we developed a roadmap that would help my new management team clear-up tax and labor issues, establish necessary controls and transparency, and recruit partners aligned with our mission. The work gave me valuable insights into key gaps in donor support for local organizations, and I gained the deepest respect for the ability of local partners to create lasting public health impact. Lessons we should heed today more than ever. The novel coronavirus pandemic has raised the stakes for all of us, and has made the local capacity to deliver health care all the more critical.

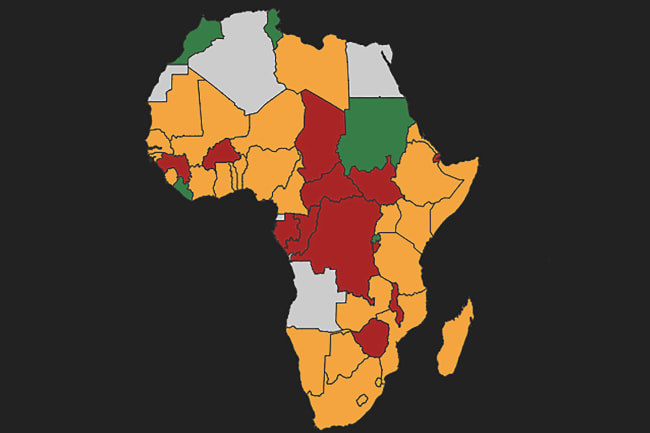

The U.S. government has made direct funding to local partners, including central and local governments and NGOs, a key part of its policy agenda for overseas development aid. And for reasons of social justice and longer-term development, local partner investments must be front and center as the United States and other donors increase support for the global response to the coronavirus.

PEPFAR has established an ambitious goal of providing 70 percent of its program funding to local partners

The first decade of PEPFAR provided experience demonstrating it was possible to shift substantial funding away from large international organizations and toward local entities. A similar approach was later adopted more broadly across USAID accounts and targets for local partner funding were increased, although not ultimately met. Now, PEPFAR has established an ambitious goal of providing 70 percent of its program funding to local partners. PEPFAR's local partner definitions allow for funding to governments, parastatals, unaffiliated local NGOs, and "spinoff" affiliates of international partners based on specific criteria—a range of options that provide strength in their diversity of capacities and support.

Potential Benefits of Working Through Local Partners

There are good reasons to work through local partners wherever possible, although there remains a need for strong and supportive international partners for the foreseeable future—particularly those whose local offices are largely run by local staff and those offering highly technical public health and management support.

Using local partners may save money by avoiding certain costs incurred by U.S.-based partners

Local organizations and staff usually have a better understanding of their environments and the strategies to engage communities in sustained pathways to improved health outcomes. And I have often witnessed how the longstanding connections these organizations have with local community and political leaders constitute the difference between success and failure in overcoming major barriers to health program implementation. Some suggest that using local partners may save money by avoiding certain costs incurred by U.S.-based partners, although this is uncertain because these savings may be initially offset by start-up/management costs both by the organization and donor.

Often overlooked, however, is the importance local organizations from a longer-term development perspective. Providing direct support to local partners achieves the greatest combination of local benefits—not just in terms of programs delivered, but institutions built for long-term sustainability- the kind that enable local careers to be built and fostered. These organizations over time enhance the local "stickiness" to keep people focused on public health gains in their own communities—a vital bulwark against the exodus of healthcare workers, public health experts and researchers in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa. Local organizations also often provide an unsung role in supporting the human rights and right to health of vulnerable, and in some cases criminalized groups—those most in need of a steady long-term partner to walk with them on the path to health and well-being.

Local organizations often provide an unsung role in supporting human rights and right to health of vulnerable, and in some cases criminalized groups

Strengthening local organizations also leverages U.S. investments in several ways. First, by making these organizations more attractive to other donors—for instance, after strengthening our management, our Zambian organization went on to receive funding from numerous European governments and new private donors. Second, a growing cadre of capacitated local organizations gives governments options for social contracting—an approach that is critical to achieving greater sustainability and equity of services for those often left behind—and that is on the critical path to achieving control of the HIV epidemic and universal health coverage (UHC). And lastly, and perhaps the most important for public health emergencies such as the novel coronavirus pandemic, local partners are a permanent resource able to pivot efficiently to support urgent national needs.

Why am I confident in the future of local organizations?

My experiences supporting local partner transitions while working in the State Department along with my four-year stint helping a large African organization achieve excellence gives me enormous confidence in the public health capacity present in many low- and middle-income countries. This confidence is a function of my experience recruiting local board members including chartered accountants, public health experts, researchers, and legal minds, and hundreds of staff with expertise in public health innovation, service delivery, diagnostics development and laboratory science, clinical trials, and management functions. There are of course many commonly discussed challenges facing local institutions and their funders, including risks of corruption that are prevalent in some regions—yet the task now is to mitigate those challenges, not avoid further localization.

Local partners are often left adrift when it comes to overcoming complex challenges at mid-later stages of their development

What more needs to be done?

More urgent than the pace of transition is the need to ensure transitions to local partners are being done well (the transactional costs of failure are high), and that successes are sustained. And to do it well, funders need to get serious about the "how." And central to the "how" is the ongoing availability of support for management functions such as finance, accounting, internal audit and governance—the strengthening of which provide not only for improved organizational performance, but also effective risk mitigation. Existing resources are usually focused on evaluating pre-award "capacity" of organizations or their function in their first year of operation. Yet, local partners are often left adrift when it comes to overcoming complex challenges at mid-later stages of their development, and there are opportunities to be more responsive to their needs.

First, funders should couple their programmatic funding with investments in local organizations' management and internal governance. We experienced an absence of support when our audit firm in Zambia highlighted financial issues spurred by U.S. government regulations. The U.S. agency providing funding could only point us to regulations that needed to be followed and lacked experience with operationalizing them in a complex financial system—yet denied our requests to use funding to hire a consultant. Although we obtained support through private donors, most local organizations lack those types of connections. Lack of support for institutional strengthening hampers many organizations from reaching their full potential, and invites opportunities for fraud and abuse to go undetected.

Donors should study how venture-capital funds provide needed services to their portfolio companies, and adapt successful approaches

Second, the United States and other funders must ensure that their own project teams include experienced managers, financial and accounting specialists, and others trained in essential operational and administrative functions, not just technical public health experts. Helping local organizations build capacity will be difficult if funders themselves lack expertise in organizational management, finance, and other internal functions. In addition to intensifying traditional approaches to the provision of technical assistance to organizations, new models such as those used in the private sector should be considered. For example, donors should study how venture-capital funds provide needed services to their portfolio companies, and adapt successful approaches such as giving local grantees "bat-phone" access to consultants with expertise in finance, accounting, and law.

Flexible approaches such as this may be particularly helpful during the coronavirus response as organizations pivot rapidly to address urgent needs and must negotiate changes to grants, contracts and agreements. Building these networks from the start is important especially when international staff may need to leave due to security or health threats. Nascent local organizations supporting health and development are likely to yield many societal benefits—arguably more than the average start-up company—and it's in our societal interest to support them at least as well.

Finally, donors should increase their risk tolerance and anticipate some challenges as local partners work to build capacity. Few endeavors in complex, resource-limited settings go perfectly, and yet few donors want to hear bad news about their grantees. But for local partners to achieve long-term success, funders must plan for—and plan to ride out inevitable hiccups and occasional backsliding. The donor community should applaud and appreciate local organizations, including government entities such as district health offices that have taken on risk to move to "prime award" status. Accountability is absolutely essential, but funders will not succeed if they revoke resources from local partners in response to every stumble.

They will collectively achieve greater impact and sustainability with these investments by ensuring more responsive support to local organizations

As the global response to the novel coronavirus pandemic proceeds, all hands are needed on deck and in addition to government and civil society leadership, both international and local organizations will play essential roles. Local organizations are particularly well positioned to leverage their permanent presence, and I expect that we will see many examples over the coming months of these and other partners going above and beyond to support the world's most vulnerable people. The United States and other donors must make transformative investments to support vulnerable countries as they work to contain the coronavirus and mitigate its devastating effects.

They will collectively achieve greater impact and sustainability with these investments by ensuring more responsive support to local organizations as they pivot to meet rapidly changing local needs.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Charles Holmes serves on the Board of Directors of the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia.