The relentless march of COVID-19 across the world demonstrates how pandemics can have disastrous consequences for health and the global economy. That's why funding pandemic preparedness is an important and necessary long-term investment we should make, now more than ever. Investing in pandemic preparedness is essential for health security and requires international cooperation. Furthermore, research and development aiming at discovery, development, and delivery of key tools that will slow and prevent pandemics is critical.

…having national response plans, resources, and the capacity to support operations in the event of a pandemic…

WHO definition of pandemic preparedness

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines pandemic preparedness as "having national response plans, resources, and the capacity to support operations in the event of a pandemic." Pandemic preparedness includes programs that aim specifically at preventing issues that arise from pandemics such as a shortage of personal protective equipment, hospital capacity, and vaccine testing. The International Health Regulations, an agreement across 195 countries that includes rules related to identifying and sharing critical information about epidemics, defines steps that its member countries should take to be prepared for global health events.

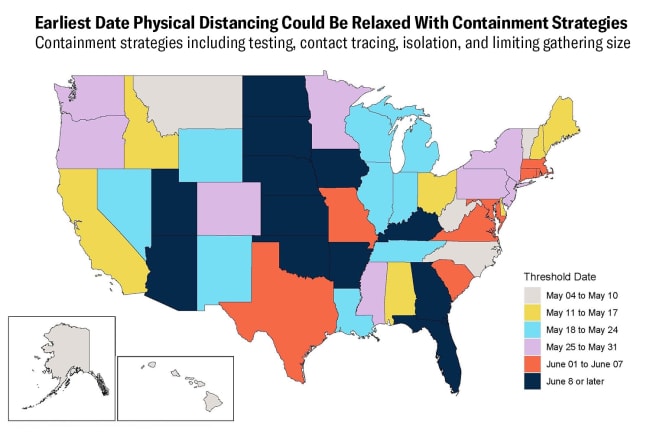

A prime example of a country with national efforts at pandemic preparedness is South Korea. Having learned from its experience with an outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015, the country was better prepared than most when COVID-19 arrived. South Korea has an infectious disease surveillance system in place that provides investigation and management guidelines for a number of different types of infectious diseases. Widespread testing, tracing, and isolation of cases, along with government advisories on physical distancing, were key for getting the disease under control. Thanks to its pandemic preparedness, the South Korean government contained the virus, and also managed to avoid applying the stringent lockdowns seen in other countries such as Franc, Italy, and the UK.

Who Funds Pandemic Preparedness and Should This Be More of a Global Effort?

While all nations have a role to play in funding pandemic preparedness, health security, and global public goods, not every country is able to invest the same amount. Globally, 83 percent of government spending on health occurred in high-income countries, while some countries such as Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo have total government spending (across all sectors) of less than $100 per person, according to new research from the Institute for Health Metrics (IMHE) and Evaluation and its collaborators. Expecting countries to contribute equally to these critical health investments (which have global consequences) is not realistic. This is where development assistance for health can and should play a key role. Development assistance for health includes the financial and non-financial contributions that aim to improve or maintain health in low- and middle-income countries.

Development Assistance for Health, 2019

Pandemic preparedness makes up only a small portion of development assistance for health.

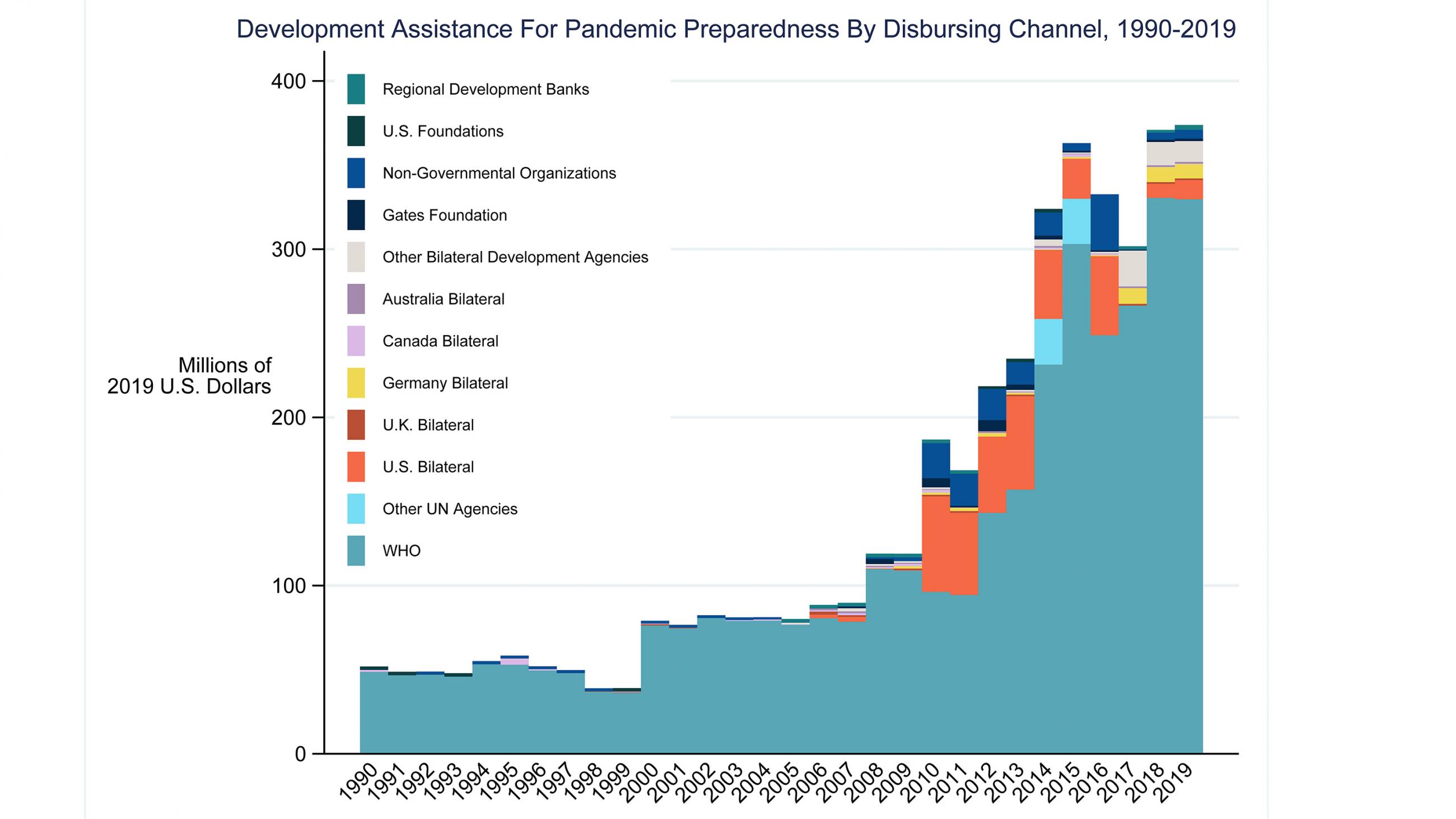

In 2019, the total amount of development assistance for health applied toward pandemic preparedness came to a total of $374 million, which is less than 1 percent of all development assistance, according to the IHME.

Less than 1 percent of all development assistance for health goes toward pandemic preparedness

Some $5.2 billion was spent on strengthening health systems, some of which should have improved countries' ability to deal with global epidemics. An additional $2.4 billion was spent on infectious diseases (excluding funds for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, which collectively received $13.5 billion in 2019). This is shown in the figure above. Those funds may also indirectly impact pandemic preparedness. In total, about 20 percent of development assistance is going to programs that are potentially impacting the ability to contain pandemics and other health emergencies, even though only a small fraction is specifically focused on building capacity to respond to and prevent pandemics.

In the past, the dramatic increases in pandemic preparedness funding have occurred following some major epidemics. This can be seen in the figure below, where there is an increase in development assistance for pandemic preparedness in 2010, after the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and again in 2014 and 2015, after the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The majority of development assistance for pandemic preparedness funding comes from high-income countries and is disbursed by WHO.

The current pandemic highlights the need to build a better-prepared global community by raising the importance of pandemic preparedness and health systems strengthening on the global agenda. These efforts will require commensurate funding. Communicable diseases cannot be contained by national borders, and an increasingly globalized world requires a global response to such diseases.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors are employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which produced the development assistance for health research described in this article. IHME is a partner on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution