Five years after the COVID-19 pandemic, the global alarm and system for emerging health threats remains underdeveloped. The probability of extreme epidemics is projected to triple, yet delayed reporting (with H3N8 avian flu, Marburg virus), antiquated digital surveillance systems (COVID-19, influenza, dengue), and coordination gaps (mpox) persist.

As the United Nations celebrates the Pandemic Treaty and new funding mechanisms, those achievements are being undermined by shrinking health budgets, the politicization of science, and the looming health impacts of climate change. Governments now are tasked with improving the current pandemic preparedness system before the next health threat emerges.

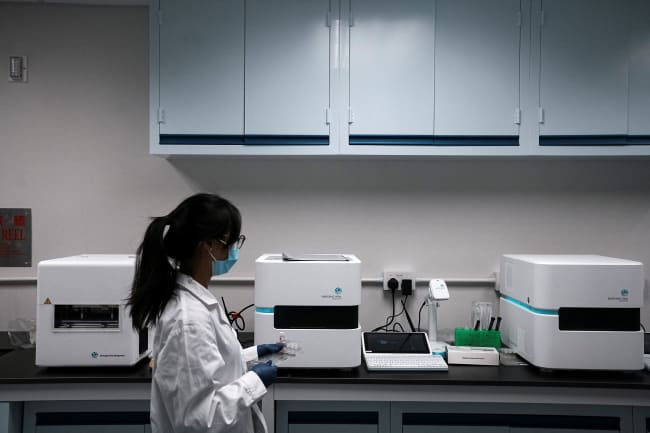

To determine how countries should build a twenty-first-century defense system on a twentieth-century budget, a global group of experts that included doctors, epidemiologists, artificial intelligence (AI) engineers, and economists convened during a closed-door session at the seventy-eighth World Health Assembly. Their conclusion was clear: Governments should stop patching broken systems and start deploying frontier technologies, such as AI, to leapfrog challenges. Analysis during the roundtable identified the major critical information gaps that hobbled the COVID-19 response and revealed how AI can fill them.

Health-related behaviors. To estimate infection risk or forecast an outbreak's spread, officials need reliable data on how people are interacting, such as gathering at points-of-interest (grocery stores and parks) and travel patterns (airports and highways). During COVID-19, public health officials struggled to understand barriers to vaccine uptake and the impact of mitigation efforts. Although platforms such as Meta's self-reporting tool generated vast amounts of data, the insights often arrived too late.

Population mobility. Countries' inability to effectively model global spread scenarios in early 2020 hurt efforts to contain COVID's spread. Migration patterns—whether seasonal, climate-induced, or general—are rarely captured by census data, hampering governments' ability to predict outbreaks or optimize resource deployment, especially across borders. The sophisticated forecasting tools that inform decisive policymaking are only as good as the data they receive.

Contextual risk. To implement broad policies such as mask mandates or school closures, policymakers need to understand their relative costs and benefits within a specific community's infrastructure, culture, and economic conditions. This challenge was critical during COVID-19 because the granular data needed to model these local risks was often unavailable.

Governments should stop patching broken systems and start deploying frontier technologies, such as AI, to leapfrog challenges

Artificial intelligence is poised to fill these gaps by processing diverse and less structured datasets to uncover insights into behavior and mobility. Foundational models, such as Google's Population Dynamics Foundation Model, can predict health outcomes with reasonable accuracy at granular geospatial levels, such as the expected number of diabetes cases or stroke in a particular U.S. zip code. This capability moves society beyond a reliance on slow, traditional surveys and analysis. In areas with low internet use, AI-enabled voice platforms such as Viamo's can provide last-mile indicators of public opinion and health concerns from vast amounts of unstructured language data.

Understanding the public sentiment and experience reflected in digital platforms and unstructured data can help identify the emergence of diseases (such as Google symptom search trends), expose public opinion about health responses (such as vaccine hesitancy), and be used to refine public health messaging.

AI can revolutionize health communication. The ability to deliver tailored guidance to individuals via mobile phones could effectively place a community health worker in every pocket. As users interact with these platforms, they can request and obtain information specific to their needs and concerns. Systematically capturing and analyzing these interactions allows health authorities to segment, customize, and refine messages that are most likely to resonate and account for local nuances.

AI can also optimize workflow and resources. Machine learning models can adapt procurement and logistics in real-time as risk signals evolve, ensuring drug availability and minimizing waste among companies. This frees a stretched health workforce from time-consuming administrative tasks, allowing them to focus on planning and response. These tools do not replace local experts but enhance their efforts and make their work more efficient.

Turning these promising use cases into a global reality, however, requires a concerted push on four fronts.

How to Accelerate Modernization

To transcend the cycle of fragmented pilots and recycled tools, governments need to invest in building the foundational plumbing of resilient systems powered by AI. Common data standards, interoperability, and digital governance should be combined with flexible, blended financing mechanisms that incentivize integration, rather than discourage it.

A lift-and-shift approach for technical solutions can promote local innovation, but countries need better product standards and market networks to scale them efficiently. To accomplish that, governments need to establish secure "sandboxes" [PDF] to leverage AI without ceding data sovereignty and tackle data hosting infrastructure constraints (technical and political). Countries should also adopt data exchange standards, such as Fast Health-care Interoperability Resources (FHIR) [PDF], given that AI models need consistent terminology to function.

Countries should rapidly deploy AI to reduce administrative burden of frontline health workers. Traditional surveillance is time and labor intensive. Although technology for automation and task assistance exists, it is underused. Efforts should focus on minimizing manual effort for data capture and reporting and assisting workflows for surveillance investigations and response.

Raw data should also be translated into actionable insights more quickly. This requires planned analytic pipelines as well as routine identification and testing of novel data sources that fill information gaps in traditional surveillance systems. Countries should focus on using rich data already generated by search engines, social media, mobile networks, maps, satellite imagery, and environmental data. These sources could overtake traditional surveys as societies' primary source of insights on population mobility and behavior. Further, federated machine learning can unlock insights while masking sensitive information.

These insights, however, are meaningless without trust. Governments should use AI to help build consensus across perspectives and tailor audience messages to foster trust in health information, communications, and the data. Behavioral science provides important evidence on effective communications, particularly in polarizing environments, and should be leveraged to address concerns. Public trust will also require clearly articulated and deliberated policies that are dynamic, have routine community evaluation, and maintain critical guardrails for privacy and security. To this end, trade-offs should be explicit, better quantifying both benefits and risks to individuals and subpopulations.

The discussions at the World Health Assembly sounded a clear call to action. Countries have the technology and the roadmap. Now they need the collective will to move beyond isolated pilots and build the integrated, intelligent, and equitable health security system the world desperately needs. The cost of inaction is too high.