"Nobody knows anything" the Hollywood screenwriter William Goldman once proclaimed —illuminating those in his own industry of the uncomfortable truth that expertise is in the eye of the beholder. This is the closest analogy we find to the global COVID-19 pandemic and how it is dealing with notions of expertise. Among the myriad of things this pandemic is bringing to light is how we must re-evaluate the old tropes of scientific expertise—particularly in global health. The novel coronavirus is a precursor to disastrous days ahead as governments and populations make decisions in order to prevent thousands of potential deaths and buffer societies to the economic dominoes that are currently falling one by one.

Decisions to prevent thousands of deaths and buffer societies to the economic dominoes that are currently falling one by one

Speaking at the government's daily coronavirus briefing on the 26th March, the United Kingdom's deputy Chief Medical Officer, Jenny Harries, when asked why the Britain was not following the World Health Organization's (WHO) recommendations for combatting the pandemic virus, said "We need to realize that the clue with the WHO is in its title—it's a World Health Organization. And it is addressing all countries across the world, with entirely different health infrastructures … We have an extremely well developed public health system in this country."

To suggest the WHO's recommendations were, essentially, for "other" countries by invoking the United Kingdom's developed country status is to assert a sort of health-care exceptionalism—and a dangerous one. Ignoring a global pool of expertise that has already shown to be effective at saving people's lives around the globe—not just for this pandemic, but previous epidemics over the years—may be putting British lives at risk.

Ignoring a global pool of expertise that has already shown to be effective at saving people's lives around the globe

One common thread in each national response is decision-making based on the best available evidence wherever it may be found. The World Health Organization, often the easy target of chagrin when global health events of this magnitude hit, has largely risen to the challenge, ensuring that the lessons learnt from one country are at least available for the next country to learn from, and hopefully avoid untold numbers of cases and deaths. Their daily press briefings since the start of the outbreak have been a master class in public health communications messaging—being technically exact and using precise urgent language. This is a unique role only the WHO can fill.

Countries that once prided themselves on being cathedrals to scientific expertise have been shown to struggle to stem the tide of the virus transmission. At the time of writing, the United Kingdom and United States stand apart from other countries in not only their unique approaches to responding to the virus, but also in cases and resulting deaths from the virus.

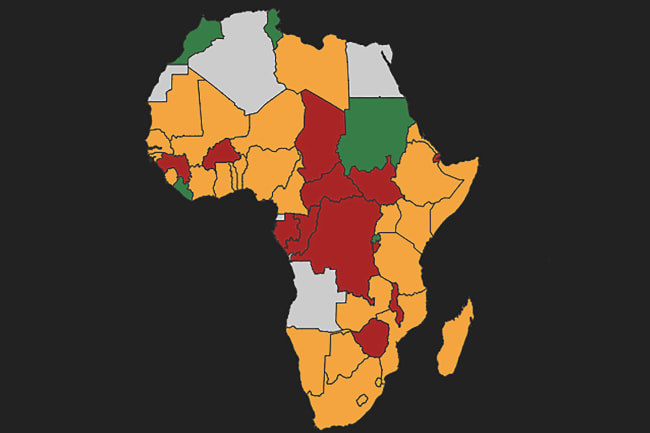

Global decisions get made in Geneva, Seattle, Washington DC, and London by global health actors whose financial resources outmatch local expertise

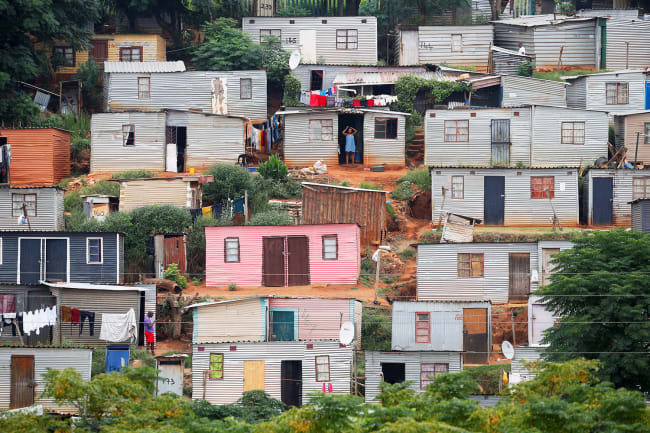

Global health expertise in the global north has always been an abundant commodity that was exported—writ large—to the rest of the world, those "other" countries. Global decisions get made in Geneva, Seattle, Washington DC, and London by global health actors whose financial resources easily outmatch local expertise. I too am guilty of this being based in a research institution in the global north. A recent New York Times opinion piece has called for a "brain trust" of the developed world to focus on a coronavirus strategy for the developing world—a brain trust of the same think tanks, news media, universities, and nongovernmental organizations that have shaped the imbalanced global health debate up until this point. The Times article largely ignores, either knowingly or unintentionally, the work that has already gone on within African borders. In February, only Senegal and South Africa had the capacity to test for the virus. By the middle of March that number was already at forty countries—due, in large part to the efforts of Africa CDC and WHO.

This false dichotomy in global health expertise is nothing new. This has been a recurring trend, with the "decolonise global health" movement among others. But this pandemic is putting it in a spotlight and making it impossible to ignore. And no doubt the discussion will continue. What is needed now is a way to reorient what we traditionally considered global health expertise and institutionalise this reorientation. Expertise is never unassailable and should not be held secure from scrutiny.

Expertise is never unassailable and should not be held secure from scrutiny

Recently, researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine writing in The Lancet recommended that to combat the pandemic, the United Kingdom will need to implement a national program of community health workers for COVID-19 response. A distinctly global south approach. Evidence that a coordinated community workforce can provide effective health and social care support at scale can be gleaned from Brazil, Pakistan, Ethiopia, and many other nations. If there were ever a time to be more community minded, it is now.

There are many more lessons to be learnt from a truly global pool of expertise. As British Prime Minister Boris Johnson was telling its elderly population not to worry and not to go on any cruises, Uganda, for example, had already implemented airport screening for incoming travellers a month earlier—all in the absence of detected cases within its borders. While videos of handwashing stations at bus stations in Rwanda had gone viral.

The lessons are there to be learnt from other countries for those willing to learn them. In a post-COVID-19 world, this will change, for no other reason than it needs to. The virus is also a precursor for a new world to emerge on the other side.