Commercial sex workers sat in a circle on the packed earth at their peer leader's home in Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India. With encouragement, the women shared stories with me and a colleague about their experiences in negotiating with their clients. As a research assistant for a doctoral project on the economic costs of HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment funded by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, I asked the women about how they value their time and the services they provided.

Fresh out of graduate school, I was fascinated by this research work and human interactions that I had never experienced in my everyday life. This early exposure to public health research sparked an interest that continues today, nearly 24 years later.

Although I continued in public health, my path has taken me far away from those women in Tamil Nadu to Christian Blind Mission, leading and supporting public health interventions in several countries in Africa.

I find myself increasingly uncomfortable with the idea and its intersections with mission, ambition, power, positionality, and identity

As I reflect on a career that grew from exchanges with peer educators in rural Tamil Nadu to a global health profession in the United States, I find myself reflecting on a popular notion in development: "Our job is to work ourselves out of a job."

Many organizational leaders recite this normative statement because it is seen as forward thinking and progressive. However, I find myself increasingly uncomfortable with the idea and its intersections with mission, ambition, power, positionality, and identity.

Early Successes: Grassroots Collaboration and Context-Specific Solutions

My first paid job involved a project funded by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) and supported by the Foundation for Sustainable Development at the Indian Institutes of Technology, Madras, a top-ranked engineering and research institute in India.

Just over two decades ago, this work was not called "global public health." Because the project was funded by UNAIDS and managed by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, I described my work as "international development."

Although this work was in the towns and villages of Tamil Nadu, I internalized the notion that, to make a decent living in "international development," I should work for an international organization based in a high-income country where I could influence policy and funding. However, I was also aware that the global forces that drove policy and advocacy had tangible effects on grassroots social change. Although I lacked a clear plan early on in my career, I recognized the importance of these collaborations and locally adapted solutions. These foundations could inspire meaningful change—approaches rooted in local expertise and lived realities.

Systemic Barriers: Power Dynamics and Country Ownership

Today I work for a large international organization. Until recently, I was also involved with a volunteer-led network of international NGOs called the Neglected Tropical Diseases NGO Network, or the NNN. Although I have witnessed remarkable successes through collaboration, I have also encountered several barriers, particularly in shifting power—the process of transferring decision-making authority, resources, and leadership roles from international organizations to local communities and actors. This concept is central to the decolonization of global health, which seeks to address historical inequities and empower those most affected by health challenges.

The mission to work ourselves out of a job aims to ensure that services and funds are eventually managed by local governments and organizations. Yet in practice this shift is often hindered by systemic barriers.

Metric- and donor-driven priorities in global health initiatives, such as global infectious diseases interventions, require investments in time, effort, expertise, and capacities to absorb failures that often lie beyond the scale and scope of small, indigenous organizations. Decisions on what is funded, when, through whom, and for how long are often made in places and cities that only influential actors can access.

Recent global policy frameworks are becoming more cognizant of these barriers. For example, the 2021 World Health Organization road map to eliminate neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) by 2030 calls for greater country ownership, emphasizing the need for local governments and stakeholders to lead policy, programming, and spending.

Additionally, initiatives such as the Mwele Malecela scholarship for women leaders and the African Research Network on NTDs (ARNTDs) signify progress in fostering indigenous expertise. For instance, the ARNTDs has empowered African researchers to lead studies on neglected tropical diseases, resulting in context-specific solutions. However, such initiatives often operate on limited budgets and may not be able to match the influence of institutions based in high-income countries in setting research agendas and allocating funds.

These initiatives and frameworks highlight a sector-wide challenge: achieving equity in decision-making and resource allocation while navigating the realities of dependence on funding and leadership that is found in high-income countries.

Personal Tensions: Identity, Purpose, and Professional Aspirations

"What does it mean to work myself out of a job?" is a question that chips away at the core of my identity, sense of self, values, and ambitions. As an immigrant in the United States who first moved here for graduate school and stayed for personal ties, would I be expected to return to where I was raised and compete for domestic public health jobs? What of my colleagues who work in high-income countries? Are we essentially advocating for a return to nativism, undermining the principles of global solidarity and interconnectedness?

Moreover, even if we concede that certain roles rightfully belong to professionals in endemic countries, what becomes of the hundreds of thousands of individuals in high-income countries who are passionate about global health? Should we pivot ourselves to domestic public health, diverting our focus to contexts closer to where we live? Or does this logic extend further, suggesting that all health jobs, global or local, should be filled by those closest to the communities being served?

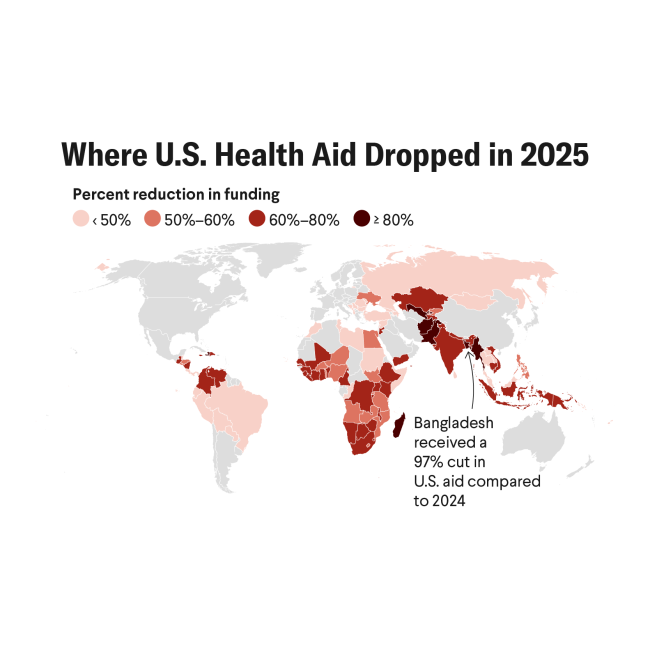

The recent cuts to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) make these existential questions even more immediate. Thousands of global health professionals in the United States have been furloughed or lost their jobs, demonstrating the fragility of international development careers and the shifting landscape of donor priorities. As we navigate these uncertainties, approaching this dialogue with nuance is crucial, acknowledging the real consequences of power shifts while advocating for a more equitable and sustainable model.

A Call for Reflection and Action

The concept of "working ourselves out of a job" demands deeper examination. It is not merely about stepping aside but also about redefining roles to ensure equity, sustainability, and effectiveness. Rather than framing this as an endpoint, we should ask, what roles do we lean out of, and what roles can we lean into?

At a global level, progress is evident in initiatives that prioritize diversity in leadership and decision-making, such as the WomenLift Health Initiative and the Women in Global Health movement. NGOs are increasingly situating senior and advisory roles in low- to middle-income countries, though decision-making power and resources are still concentrated in high-income countries. At an individual level, those grappling with questions of power, inequity, and purpose must reflect on how they can contribute to a more balanced and just global health ecosystem.

My path—as a South Asian woman working in global health—is a product of progress and a testament to the systemic inequities we strive to dismantle. My work is driven by a deep commitment to improving health equity and justice, yet it is intertwined with the privileges and challenges of operating within an inequitable system.

Let us move beyond platitudes and engage in meaningful dialogue and action. Redefining our roles is not a call for redundancy but an opportunity to align our work more closely with the principles of equity and sustainability we all aspire to achieve.