Facing criticism of the federal government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic, President Donald J. Trump made an unexpected Twitter announcement on immigration on April 20. The United States would immediately suspend immigration for green card holders to protect "the jobs of our GREAT American Citizens" and, as the following presidential proclamation outlined, conserve "our healthcare system at a time when we need to prioritize Americans." The problem with the new policy: numerous studies show that far from hindering America's economy, immigrants greatly contribute to it. And as medical and food shortages threaten communities across the United States, policymakers will best succeed with solutions that support the immigrants who underpin the security of our medical and food supply systems.

Policymakers will best succeed with solutions supporting the immigrants who underpin the security of our medical and food supply systems

Opportunistic targeting of immigrants and migrant workers is not confined to the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided fresh cover to governments all over the world for the same old discriminatory policies. Hungarian President Victor Orbán, who has spent the past decade consolidating his power and stoking fears about Muslims, refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers, has used the pandemic to drag his country further into authoritarianism and blamed undocumented migrants for the spread of coronavirus. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's lockdown announcement, issued with only four hours warning, resulted in thousands of displaced migrant laborers swarming train stations to seek safe return to home villages. Many still languish in cities, abandoned by the economy that depended on their cheap labor until it was inconvenient. And in Malaysia, migrant workers and even their children have been imprisoned due to COVID-19 suspicions.

The United States also runs on migrant labor, and in the midst of a raging domestic pandemic, our medical system would likely collapse without immigration. One in four doctors in the United States are immigrants and 17 percent of health-care workers are foreign born. More than twenty-nine thousand health-care professionals are Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, or Dreamers, as they are popularly known. Despite a critical shortage of doctors and nurses in the United States, the Supreme Court is expected to announce in June their decision on potentially shutting down the DACA program, which could put thousands of health-care workers at risk of being deported—in the midst of an unprecedented public health emergency.

One in four doctors in the United States are immigrants and 17 percent of health-care workers are foreign born

Even with the Trump administration's decision to exempt health-care professionals from its recent immigration ban, foreign-born doctors still face endless green card backlogs or bureaucratic hurdles. Just last week, Julia Iafrate, an intensive care doctor fighting COVID-19 in hard-hit New York City, found out her green card application had been denied, even as she risked her life to treat American patients. And immigrants serving in critical nonclinical hospital jobs as janitors, clerks, and food service staff also face tremendous danger to serve the public good, while being paid minimal salaries. America's medical staff shortages could be better addressed by improved immigration policy, fair wages, and paid sick leave, not cheap xenophobia or sentimental ad campaigns.

Even if an American is lucky enough to avoid a hospital visit during the pandemic, it's hard to ignore COVID-19 at their local grocery. As the United States starts to experience food shortages, policymakers will also need to recognize that immigrants play an outsized role in securing the U.S. food supply. Some 53 percent of farm workers are born outside of the United States, and many are undocumented and vulnerable. Although the Trump administration deemed farmworkers as essential workers in March and exempted them from immigration bans, other policies undercut their safety and ability to do their jobs. The U.S. Department of Agriculture's April attempt to lower the wages of farm workers on H2A visas, who are already severely underpaid for their work, combined with the lack of health protections for migrant workers, will do nothing to secure the food supply. Workers could have to leave their jobs due to sickness, or simply decide they do not want to continue risking their lives for such low pay.

Some 53 Percent of farm workers are born outside of the United States

Did your local Wendy's run out of hamburger meat this week? Meat processing plants have also emerged as COVID-19 hotspots, with as much of 80 percent of their workforces made up of immigrants and even refugees who fled conflict to now work in heartland state meatpacking jobs as "modern slaves." Instead of implementing robust workplace protections that address COVID-19 health risks, the Trump administration invoked the Defense Production Act on May 1, mandating that meat processing plants stay operational, making workers choose between their jobs and exposure to the novel coronavirus. Policymakers cannot allow a social contract to stand that says your work may be deemed essential while your health and safety are not.

America could learn from other countries that the lack of a social safety net for migrant workers quickly becomes a problem for everyone in a pandemic. Perversely, nationalistic anti-immigration policies, ostensibly designed to improve the well-being of citizens, only threaten public health.

Perversely, nationalistic anti-immigration policies, ostensibly designed to improve the well-being of citizens, only threaten public health

Singapore, which initially responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with successful policy measures, soon floundered as the novel coronavirus resurged among Singapore's migrant population, who live in dormitories that house as many twenty foreign workers in a single room. By excluding foreign workers from its social safety nets, Singapore put its citizens at renewed risk. Here in the United States, the recent $1,200 stimulus check and expanded unemployment insurance excluded any family members who file joint taxes with undocumented immigrants—despite undocumented immigrants paying billions of dollars in federal taxes every year, many working as essential workers on the front lines of the COVID-19 crisis. These desperate families are now showing up to food banks in lines stretching for blocks, with spillover effects ahead for struggling state budgets.

If the United States hopes to weather the pandemic with a stable medical system and food supply, Congress must act to protect the immigrant workforce—even if the Trump administration will not. On May 5, bipartisan Senate leaders introduced a promising new bill to dedicate fifteen thousand employment-based visas to immigrant doctors and twenty-five thousand visas to foreign-born nurses. The Healthcare Worker Resiliency Act [PDF] would help the U.S. medical response to COVID-19, providing needed reserves as countless health-care workers contract the virus and hospitals manage staffing shortages.

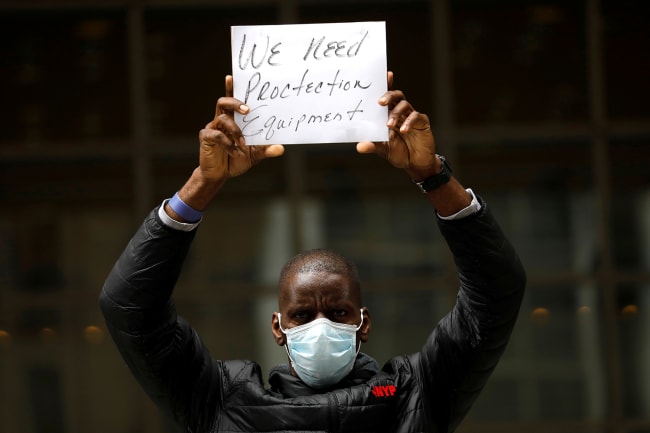

If meat processing plants are essential, employers should be required to provide protective equipment, paid sick leave, and workers' compensation

Congressional leaders should also legislate new emergency workplace protections for meat processing and migrant workers, where employees work elbow to elbow, unable to socially distance. If meat processing plants are essential, employers should be required to provide personal protective equipment, paid sick leave to employees, and workers' compensation to employees who contract the coronavirus at work. State Department H2 visa changes to wave in-person interviews for lawful seasonal farm workers are a positive development by the Trump administration, but these already-vulnerable workers also need access to health care and the ability to take paid leave when they become ill, instead of infecting their coworkers. Additional funding is also needed to support the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and other state agencies that protect worker safety, so oversight authorities can adequately respond to local workplace outbreaks.

COVID-19 has laid bare the United States' own unspoken economic caste system, revealing how easily essential workers can be abandoned for the sake of political expediency. Restricting immigration or closing borders will not help America's pandemic response—our house is already on fire. On April 27, CBS reported that 20 percent of all cases of the novel coronavirus in Guatemala were found among people the United States had recently deported and who had contracted it here.

Should human rights and economic arguments not win the day with American policymakers, maybe fear of running out of food or nurses will

In April, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson praised the two immigrant nurses who helped save his life from COVID-19, saying, "It's hard to find the words to express my debt." Still frail from his recuperation in a National Health Service intensive care unit, Johnson recognized what the Trump administration has not: that immigrants critically support our national response to COVID-19. Should human rights and economic arguments not win the day with American policymakers, maybe fear of running out of food or nurses will.