While some parts of the world settle into some type of normalcy at the half-year mark of the coronavirus pandemic, Zimbabwe has to cope with a continuing public health catastrophe as well as COVID-19. The "#ZimbabweanLivesMatter" hashtag calling for global action on unfolding events in the country has been trending on social media. A spike in COVID-19 cases is occurring against the backdrop of a failed health-care system. The situation is compounded by economic instability with a currency that is rapidly losing value, widespread hunger due to drought and political unrest with ongoing calls for protests against the government's mismanagement.

Nurses in Zimbabwe currently earn less than $30 per month, and a single COVID-19 test in the country can cost about $60

From July 28 to August 3, 2020, 1,371 COVID-19 cases were diagnosed, the largest number of cases in one week since the start of pandemic—adding more than a quarter of the total number of cases—4,075—since the first case was identified on March 20. Overall, only 64,634 PCR tests have been conducted. As of August 4, Zimbabwe had conducted Four tests per one thousand people in comparison to fifty-two and six tests per thousand in South Africa and Kenya respectively. Zimbabwe is lagging behind, mostly due to inadequate test kit supplies, long test delays in the public sector, and expensive tests in the private sector. The cost of a single test in the private sector is approximately $60 while a nurse in Zimbabwe currently earns a salary equivalent to less than $30 per month. In addition to this, the procurement of personal protective equipment (PPE) has been marred with allegations of gross corruption. While inadequate testing means that the country does not have control on the virus' spread, many other issues are adding to and exacerbating the impact of the epidemic and have ignited a rapidly unfolding humanitarian crisis in Zimbabwe.

Politics and Corruption are Hampering the Public Health Response

In July, internationally renowned journalist Hopewell Chin'ono uncovered irregularities in government processes for PPE supply to the tune of $60 million. He was subsequently arrested for "inciting public violence."

Vice-President Chiwenga has no medical background, which leaves concerns about his capabilities for the post during this time

Still, this discovery most likely led to the removal of Minister of Health and Child Care Obadiah Moyo on July 7 for misconduct. Just prior to this, Agnes Mahomva, the permanent secretary of the ministry, was reassigned in May. Moyo's removal and Mahomva's reassignment left a huge, glaring vacuum in the leadership of the health-care sector just when direction and decisive action to curb the spread of COVID-19 was needed the most. Both posts were vacant until August 3 when, air commodore Jasper Chimedza, was appointed permanent secretary and Constantino Chiwenga, the vice president of the country, was appointed minister of health and child care on August 4. Worryingly, both Chimedza and Chiwenga held senior posts in the Zimbabwe Defence Forces prior to these appointments. Vice-President Chiwenga also has no medical background, which leaves concerns about his capabilities for the post during this time.

The government has alleged that in order to curb the spread of COVID-19, strict and prolonged lockdowns must continue. On July 22 the president of Zimbabwe announced another indefinite lockdown ahead of planned protests on July 31.

On July 22 the president of Zimbabwe announced another indefinite lockdown ahead of planned protests on July 31

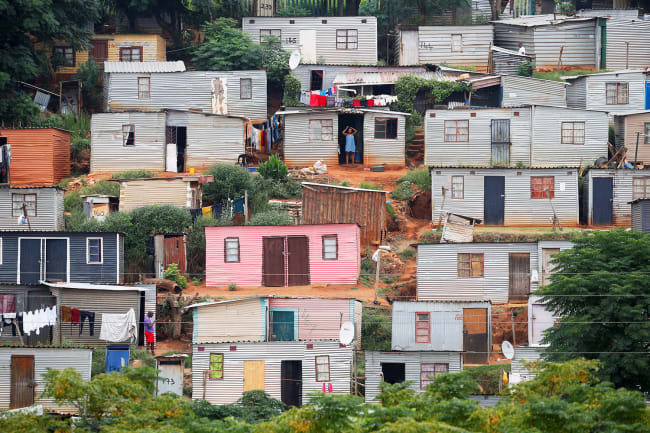

Part of the measures included a ban on intercity travel and a dusk-to-dawn curfew. All non-working people are required to stay home unless accessing food, water or essential health services. The Zimbabwe Republic Police released a circular on July 25 stating that at roadblocks, individuals must produce letters from employers or medical cards/prescriptions. This limits all movement, including for people who want to access health services. The police are working hand-in-hand with the military to enforce lockdown measures. Both groups have been called out for an inconsistent, heavy-handed, and sometimes corrupt approach, including demanding brides from those who break lockdown regulations. These lockdown measures have been criticized for being political rather than having real public health motivations due to lack of data and for their negative impact on an already crippled economy. The majority of Zimbabweans are informally employed. Extended lockdowns hit them hard by directly curtailing their ability to earn money and feed their families. The food security situation in Zimbabwe was already fragile and threatens to worsen with these mandates.

Other Health Services Are Failing, and People Are Suffering

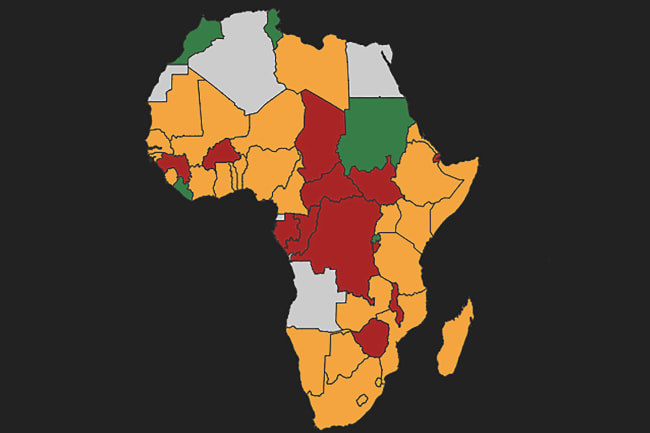

Zimbabwe has had a prolonged generalized HIV epidemic and one of the highest rates of HIV prevalence in the world at 13 percent. Lockdown measures and travel bans make it difficult to access health services, and more than 1.3 million people who are currently living with HIV in Zimbabwe need to regularly obtain lifesaving HIV treatments to stay healthy. In addition to this, tuberculosis (TB) and Malaria are also endemic—and often infect people already infected with HIV.

Zimbabwe has one of the highest rates of HIV prevalence in the world at 13 percent

For the past ten years, Zimbabwe's health system has been degraded because of lack of funding and mismanagement, which has resulted in largely non-functional health-care facilities across the country with limited staff and ongoing drug shortages. Last month, seven out of eight newborn babies died in one night one of the country's largest referral hospital. The limited health services that exist are now beginning to overrun with severe cases of COVID-19, and there have also been reports of both public and private hospitals refusing to admit patients who are COVID-19 positive or do not have COVID-19 results. Within the public sector, results from free COVID-19 test sometimes take more than seven days to be returned. In the private sector results can take between 48-72 hours. This too has led to preventable deaths among people in need of emergency health services with increasing reports of avoidable deaths at home and in hospital car parks.

If left unchecked the situation in Zimbabwe is prone to deteriorate further. We are likely to see COVID-19 cases rise, not fall in Zimbabwe. Doctors and nurses have been incapacitated and on strike since March, demanding fair living wages and adequate personal protective equipment. Only two hospitals, with fifty-six beds between them, are currently treating COVID-19 patients in the capital city. The public sector hospital has been full for weeks. Due to this perfect storm, Zimbabwe risks uncontrolled infections among health-care workers, as seen in other African countries. With less than two doctors for every 10,000 people endangering the health workforce denies us of the few heroes we have left who are fighting against COVID-19 and everything else.

Only two hospitals, with fifty-six beds between them, are currently treating COVID-19 patients in Harare, Zimbabwe

The world looked away, when our economy crumbled and when our children were subjected to hunger in a country which was once called the breadbasket of Africa. It must not look away now when this pandemic rages through our communities and the government enacts human rights violations to cover it up. The global community must intervene. Leaders both within the country and around the world must ensure that Zimbabweans have access to affordable and timely tests, that health care workers are paid and protected, and that all allegations of mismanagement of funds to procure essential commodities are thoroughly investigated and that those responsible are prosecuted.