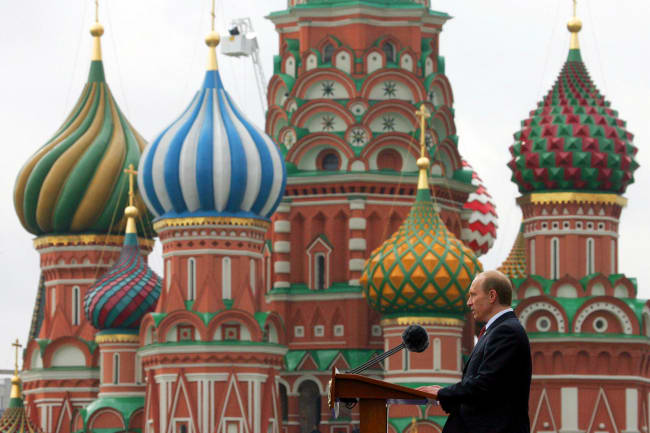

So he's all in. President Vladimir Putin's dramatic COVID-19 vaccine announcement this week—not only has Russia bypassed all other competitors in the race for first approval, but one of his daughters has already received two doses of the vaccine—is appropriately raising eyebrows in the global scientific community. It's a tricky risk-reward calculation by a leader desperate for a big political win.

No safety or efficacy data have been published, let alone peer-reviewed

The headlines in the West have rightly worried about the extent to which Russia's accelerated vaccine development timeline has sidestepped key elements of the standard approval process. It appears that only a few hundred people, mostly from the military, have participated in clinical trials of vaccine prototypes over the last two months. No safety or efficacy data have been published, let alone peer-reviewed. Russia's claim that the vaccine candidate produces antibodies is promising—but not sufficient to demonstrate safety and efficacy. The obligatory third phase of clinical trials involving tens of thousands of carefully recruited and closely monitored subjects is apparently being curtailed, dovetailed with early public delivery to health-care workers, teachers, and other government employees.

Prominent voices in Russia's own scientific community are sounding warnings about the vaccine's safety. The Russian Association of Clinical Research Organizations, an industry group that includes international partners like Bayer, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Novartis, has urged the Ministry of Health—in writing—to postpone registration of the vaccine until proper final-phase trials have been completed.

Russia's government lays claim to 47 different COVID-19 vaccine candidates—but only two are serious

The Russian government lays claim to forty-seven different COVID-19 vaccine candidates, but only two are serious: the one just registered, from the Ministry of Health's Gamaleya Center, whose pedigree dates back to 1891, and the other from Vector, founded in 1974 as the Soviet Union's premier biological weapons lab—and later transferred in a civilianized incarnation to Rospotrebnadzor (the main consumer affairs regulator). The vaccine race, with Gamaleya apparently leading Vector by about a month in the development timeline, follows institutional combat between the two earlier in 2020 over production of COVID-19 tests. Throughout January, Vector held a monopoly on possession of strains of the virus, blocking other labs from developing test kits. The Ministry of Health responded by withholding patient records from Vector.

Ultimately a combination of flawed testing technology and bureaucratic morass forced Vector to change tack, and a wide range of other public and private laboratories were ultimately permitted to work with samples and develop tests. But the gauntlet was thrown, and Putin has reportedly exploited this competition by exerting pressure on each lab to outpace the other.

Russia's propaganda machine pulled out the stops in launching a 7-language "Sputnik Vaccine" website

It's not hard to understand the motivations behind Russia's vaccine strategy. Ever since the humiliation of the Soviet collapse thirty years ago, Russia's been in search of opportunities and venues to reassert its position as a preeminent great power. Leading the way out of a once-in-a-century pandemic, especially as the virus starts to decimate low- and middle-income countries in Latin America and Africa, could boost Russia's reputation in ways it might not have imagined even a year ago. Russia's propaganda machine is pulling out all the stops, most recently with the launch of a "Sputnik Vaccine" website in seven languages—be sure to turn up the volume and push the "play sound" button as the page loads for full effect. The site purportedly aims to combat the "misinformation campaign launched against [the vaccine] in the international media."

Russia has a rich history in virology and vaccine development. In the 1950s, Soviet collaborators were essential to the initial production and testing of Albert Sabin's oral polio vaccine.

The Soviet Union was essential to the initial testing of oral polio vaccine in the 1950s and the eradication of smallpox in the 1970s

The Soviet Union donated more smallpox vaccine to the World Health Organization than all other countries combined during the eradication campaign in the 1960s and 1970s, and its freeze-drying technique provided stability for the vaccine at high temperatures, enabling its use in tropical climates. Russian scientists tout the durability of that legacy: Russian labs have continued to focus on virology while the rest of the world has taken a turn toward molecular biology, and they can tap into a decades-old industrial base for mass production of vaccines. They claim that use of an existing platform already approved for earlier Ebola and MERS vaccines has given them a head start, though WHO still lists those only as "candidate vaccines."

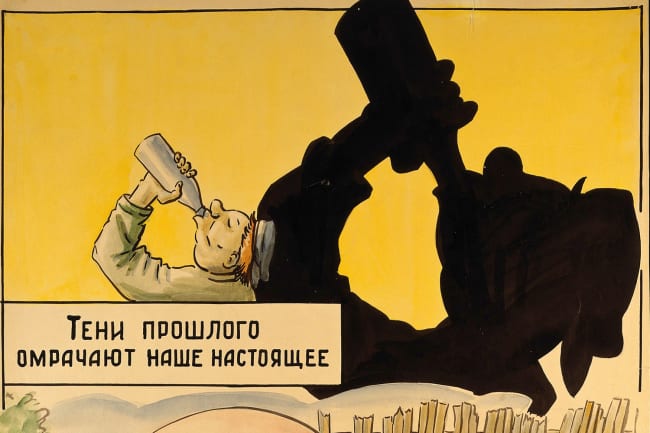

Much of that capacity, however, hasn't recovered after being hollowed out by economic collapse and brain drain in the 1990s. Instead, post-Soviet Russia has a history of premature claims representing, at best, wishful thinking across a wide range of scientific and technological areas, from a long-promised AIDS vaccine to generation-skipping superweapons.

Many Soviet-era vaccine plants still fail to meet international standards

While the Putin regime has invested significantly in pharmaceutical research and production over the last ten to fifteen years, governed by a "Pharma-2020" strategy aggressively designed to replace imports with home-grown products, many Soviet-era vaccine manufacturing plants still fail to meet international standards. Certainly there are brilliant scientists working on vaccine development in Russia. But there just isn't a track record of Russian-produced innovative drugs or vaccines getting regulatory approval for Western markets. There's no history or reputation for meeting export-level quality standards.

During the current pandemic crisis, though, all bets may be off.

Philippines' Rodrigo Duterte announced he is ready to take delivery and to be the first person to receive the vaccine in public

Desperation is driving potential customers to keep all possible options open, so that Russia's claim of wide interest in its vaccine—from more than twenty countries, including India, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, and even some preliminary inquiries from American companies—is plausible. The Philippines' President Rodrigo Duterte has already announced that he's ready to take delivery and to be the first person to receive the vaccine in public. With the United States hoarding COVID-19 treatments and refusing to participate in international vaccine distribution arrangements to facilitate access to lower-income countries, Russia could score some serious public relations points through offers of free or affordable licensing and production agreements.

But Putin's audience may not be primarily international. Being first out of the gate with a vaccine could go a long way toward recapturing Putin's aura of indispensability at home. Unlike some other heads of state, he hasn't enjoyed a coronavirus-related "rally 'round the flag" bump in public approval over the last few months.

Propaganda trumpeting Russia's vaccine victory has blanketed its state-controlled media for weeks

Most Russians perceived his initial pandemic response as passive and anemic, a sharp contrast to the decisive actions taken by some sub-national leaders, including Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin. Putin's trust rating fell to a new all-time low in July. Propaganda trumpeting Russia's vaccine victory has blanketed its state-controlled media for weeks, but it appears there's still a lot of persuading to do. A mid-June national poll [PDF] by the respected Higher School of Economics in Moscow was revealing. It found that fewer than 16 percent of Russians plan to be vaccinated immediately; 7 percent will wait a few months; 11 percent will decide over the course of the next year; 4 percent are holding out for a foreign vaccine; and fully 38 percent say they will never be vaccinated against coronavirus.

The Vaccination Plans of Russians, According to a Major Poll

Uncertainty reigns amid high hopes for a vaccine and a backdrop of general distrust in official data

A considerably less scientific study—an online poll run by a national tabloid over the last week—produced results that were partially more reassuring, with half of respondents saying they'll take the vaccine straightaway, but 9 percent claimed that COVID-19 doesn't exist and 6 percent backed a conspiracy theory about vaccines as delivery systems for microchips intended to monitor our behavior.

Only 31 percent of Russians trust what the government is telling them

These results aren't surprising against a backdrop of generalized distrust in official data. Another national poll conducted in July found that only 31 percent of Russians completely or largely trust what the government is telling them about the pandemic, while 65 percent say they only partially believe official news or don't believe it at all. It doesn't sound like this is a population ready to serve themselves up as test subjects for an experimental vaccine.

The bottom line: If Russia's product is safe and if it actually works, that's great news all around. Multiple constituencies around the world would benefit from a buyer's market, with robust political and economic competition among multiple providers of safe, effective COVID-19 vaccines.

It would be tragic if Putin's "Sputnik moment" turns out to be a fizzled publicity stunt that erodes trust in science and costs Russian lives

But cutting corners, as Russia's clearly doing, would be quite a gamble even for a country with an internationally competitive pharmaceutical industry and pre-existing innovative vaccine program. For Russia, the potential downsides are even more significant. If its vaccine doesn't work as advertised, the reputational damage, both within and outside the country, would be immense. Preconceived notions that Russia's not ready for prime time would be confirmed, under a global spotlight. The tangible epidemiological risks are also enormous. Premature rollout of an ineffective vaccine would increase the vulnerability of Russians and other potential users to infection if they wrongly assume they can ease up on physical distancing, mask wearing, and other public health measures. Anti-vaxxers would have a field day with high-profile adverse events following administration of an unsafe vaccine, probably depressing uptake when a credible vaccine is eventually released. It would be tragic if Putin's "Sputnik moment" turns out to be a fizzled publicity stunt that erodes trust in science and costs Russian lives.