This article includes a discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know needs help in the United States, call the national suicide and crisis lifeline at 988.

In early February, a psychologist in Kharkiv working for a humanitarian organization funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) received a call from a client reporting suicidal ideation. Normally, its staff would provide emergency intervention and a long-term care plan to ensure the client's safety. Given the USAID stop-work order, however, the psychologist was unable to intervene. The psychologist later learned the patient had attempted suicide, according to the program's coordinator, who spoke with Think Global Health.

On the conflict's front lines, a soldier in Ukraine's four hundred and twenty-fifth battalion was shot in the knee. After undergoing multiple unsuccessful surgeries, his doctors told him he would be unable to walk again without a U.S.-provided implant. Given cuts to U.S. foreign assistance, however, the implant is no longer available, reported Igor Lavreniuk, the soldier's deputy commander.

These stories represent only a fraction of the Ukrainians left with unmet care after sweeping budget cuts to USAID. According to the Center for Global Development, of the approximate $50 billion in USAID grants cut after Secretary of State Marco Rubio's review of foreign assistance programs, Ukraine—with $1.4 billion curtailed—is the single biggest loser.

"Overnight, all of our programming came to a screeching halt," the humanitarian organization's mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) program coordinator explained. Think Global Health is withholding the names of the organization and its staff throughout this article because of the potential for reprisals.

Ukrainians and humanitarian assistance workers on the ground have felt the brutal immediacy and severity of the cuts

Ukrainians and humanitarian assistance workers on the ground have felt the brutal immediacy and severity of the cuts. But the shifting and chaotic guidance on how to implement them has left aid organizations floundering as they attempt to maintain some continuity in care.

"I'm really proud that I work here and that I help my country in such hard times. We really value what we do, and we'd like to proceed with our work," said a logistics officer for the humanitarian organization, 88% of which staff in Ukraine are Ukrainian. "I'm depending on this humanitarian assistance from USAID, and tomorrow I don't know if I still have a job."

Ethical Quandaries

Faced with uncertainty, public health workers are weighing the value of interventions in certain conflict zones over others, cutting entire offices or programs deemed less critical.

"We're trying to make good ethical decisions with the information we have, but right now there isn't a way to provide services in an ethical way," the MHPSS program coordinator explained. To prioritize continuity of care, she has encouraged her case managers to stop taking on new clients and to seek referrals for their high-risk clients instead.

The monthly average of services the organization provides has in 2025 already dropped by more than 80%, according to the group's deputy director. The organization closed offices in Mykolaiv, Odesa, and Dnipro—and is in the process of shuttering programs in Sumy, a disputed region bordered by Russia. Programming in Kharkiv, which suffered a major Russian offensive in 2024, is on hold. The MHPSS logistics officer, whose role includes arranging interventions in recently de-occupied zones in Ukraine to assess and repair damage, spoke about the difficult decision to shift focus away from the south to sustain efforts on the eastern frontlines.

"We are in a war," he said. "We must react fast."

The moral dilemmas stemming from aid cuts extend to the highest levels of the Ukrainian government, which is forced to balance new humanitarian assistance holes against urgent military priorities.

"You need to take the money from somewhere else, and there's not much you can take the money from," explained Lavreniuk. His battalion, which is responsible for long-range drones and real-time monitoring of battlefields, is already not adequately funded and relies on fundraising to remain operational.

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy's reaction in early February to USAID cuts made clear his stance on the country's priorities: "We aren't going to complain that some programs have been frozen, because the most important thing for us is the military aid and that has been preserved."

Despite ongoing health demands, Ukraine's wartime priorities have shifted away from health care and toward defense, health spending decreasing [PDF] from 11% of the national budget in 2021 to just 4.9% in 2023. Conflict zone hospitals faced with overcrowding and shortages have similarly favored military needs, often prioritizing injured military personnel over civilians, according to Lavreniuk. He anticipates that cuts to humanitarian aid will further decrease the capacity to care for civilians in conflict zones. "Hospitals will face more shortage, which will lead to more death," he warned.

"I Can't Trust Anything"

The MHPSS program received the stop-work order on January 26 as their program coordinator prepared for a trip to Odesa for a field visit. After receiving an emergency notice from the organization's contracting officer, she was forced not only to cancel the visit but also to close the Odesa office and suspend all humanitarian assistance programming across Ukraine. Meanwhile, the department's deputy coordinator had been organizing a training on a mental health supervision model to integrate across Ukraine's social policy and education ministries, but that too was abruptly halted.

In the week following the stop-work order, the MHPSS organization scrambled to close offices, lay off employees, and cut programs. But then, unlike many USAID-funded programs, the group received a lifesaving waiver from the U.S. State Department, technically allowing their programming to continue.

Yet funding remained frozen and the organization quickly began running out of money. On March 7, the MHPSS program received reimbursement for their January and February expenses. But any future funding is unclear—even for the reimbursement of their April budget. Soon after the waiver's creation, Council on Foreign Relations Global Health Senior Fellow Prashant Yadav commented that USAID cuts disrupt global health supply chains, hindering the continued implementation of such lifesaving programming.

"I can't trust anything," the department coordinator explained. "Since the stop-work order, every day feels like multiple days because things change so rapidly."

The State Department has shared these high-stake updates to recipient organizations informally, adding to the confusion. "Some people from the American government communicated to their partners. But for us, there was no such official communication," the MHPSS organization's logistics officer explained, noting that most of the information he received about the cuts to his organization came through word of mouth.

From his perspective, the shifting and informal messaging is tied to the unpredictability of President Donald Trump's foreign policies. "Two weeks ago was one situation, and now it's another. One day, we have money for activities, and the next day we don't," he said.

The dismissal of USAID staff has further obscured the assessment and disclosure of the cuts' immediate ramifications. "I want to see the literal life and death consequences of what's happening," the program coordinator explained. "But because they've been laying off federal workers, no one is left to document anything."

Health Needs After Three Years of War

The humanitarian cuts are unfolding amid a changing health landscape. Andrej Slavuckij, deputy program director for Doctors Without Borders, also known as Médecins Sans Frontières, and former chief of health for the nutrition and HIV-AIDS section for UNICEF Country Office in Ukraine, noted that three years of war have generated chronic health needs that "carry the risk of lifelong consequences if not addressed properly."

These conditions often require physiotherapy, psychological support, and postoperative care—services not widely available in Ukraine before the war, according to Slavuckij. The MHPSS program coordinator added that children have been particularly affected by school closures, family separations, and sleep disruptions caused by perpetual air raid alerts. Veterans often struggle to reintegrate into communities and suffer from substance abuse and depression. Many elderly, disabled populations who were unable to evacuate conflict zones remain isolated from quality health care and have unmet basic needs.

"These are regular people who want to live a simple life," the logistics officer explained. "No place in Ukraine can be considered safe," Slavuckij said.

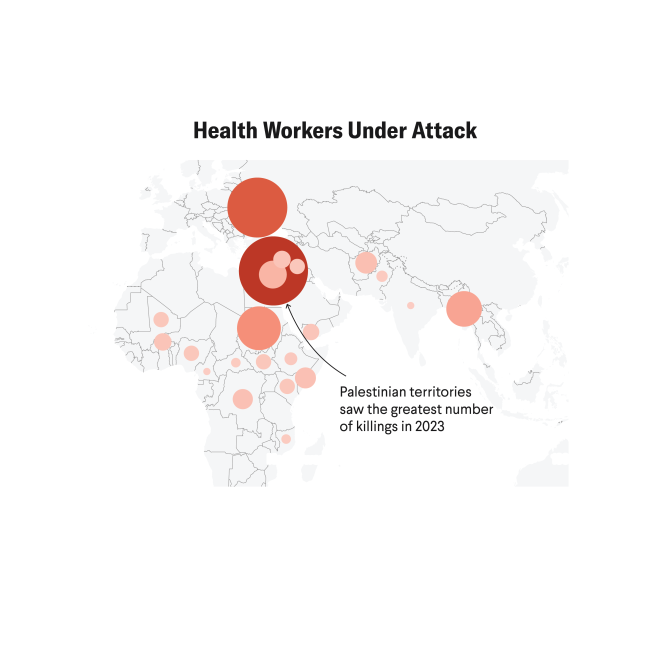

Damaged medical infrastructure limits organizations' ability to address the health needs of affected populations. Confirmed attacks on health-care facilities in Ukraine since 2022 total 2,215, contributing to a Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment taskforce estimate that $14.2 billion would be needed to rehabilitate the health sector in the next decade.

In April 2024, the Doctors Without Borders office in the Donetsk region was bombed and completely destroyed, and mobile teams "could not find a single building with the structural integrity needed to serve as a makeshift clinic" in many towns in conflict zones, according to Slavuckij. Doctors Without Borders, which does not rely on government money for work in conflicts zones, he added, is evaluating the repercussions of USAID realignment, and his comments do not reflect the organization's positions on the cuts.

Filling the Gaps

President Zelenskyy acknowledged his government's plan to examine the holes left by aid cuts and "determine which ones are critical and require solutions now," as they begin to appeal to other sources of funding. But Ukrainian humanitarian organizations already faced unmet aid requests before the 2025 aid cuts. According to the MHPSS deputy coordinator, programs across Ukraine requested $390 million in 2025 from the European Commission—the largest European donor to Ukraine's humanitarian war efforts—but only $140 million, almost four times less than the commission's 2022 Ukraine budget, was allocated.

Assistance workers also expressed doubts about the feasibility of turning to other sources for aid. The humanitarian organization, which has begun targeting European and private donors, learned that it will take months for new donors to adjust their budgets. European budgets have already been allocated this year, so many countries' hands are tied, the department coordinator explained. As of February 17, fewer than 1% of Ukrainian organizations that requested alternative sources of funding had received it.

"I don't know who survives this generally," the MHPSS coordinator stated, worried about the decreasing appetite for global assistance. "The ramifications are unfathomable."