When William Shakespeare's tragic and doomed character Hamlet famously asked whether it was better "to be, or not to be," he articulated the crushing mental strain felt by anyone facing "a sea of troubles"—lines more relevant than ever today. COVID-19 has had immediate, highly visible, and permanent effects on society, including the infections and deaths the pandemic has caused, the suffering and lingering aftereffects faced by individuals who have had the virus, the stress COVID-19 has placed on health systems, and the pandemic's economic devastation, which has led to secondary shocks like widespread food insecurity and people forgoing health care. In addition to these strains on the system, COVID-19 has also placed a huge mental health burden on the individual, which constitutes a sort of hidden, creeping burden.

Nearly nine million U.S. Facebook users shed light on the mental health burden COVID-19

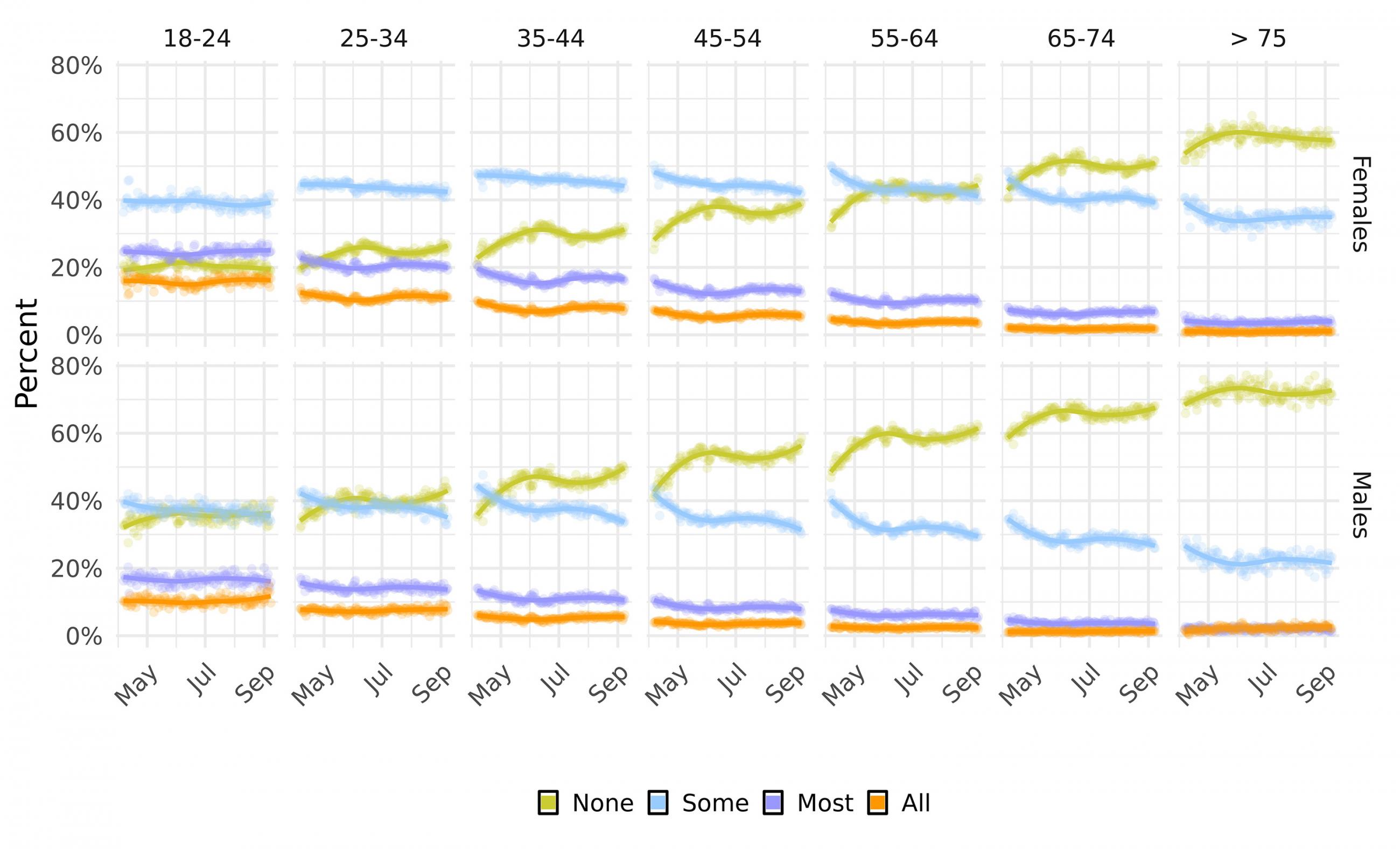

Quantifying the degree to which the lockdowns, social isolation, and stress brought on by COVID-19 have affected mental health has been difficult. However, new data from a survey of nearly nine million U.S. Facebook users sheds light on the mental health burden COVID-19 has caused. For example, during the week of April 15 (when there were roughly 200,000 infections per day in the United States) 38 percent of survey respondents reported feeling depressed some of the time, 9.5 percent most of the time, and 5 percent all of the time—for total of 52.5 percent of users feeling depressed at least some of the time, compared to 47.5 percent of respondents who reported feeling no depression at all.

The survey was conducted jointly by Carnegie Mellon University and Facebook and was limited to Facebook users and therefore may not be representative of the general population (more on that later). And what the Carnegie Mellon/Facebook survey can't reveal are the number of folks whose symptoms are severe and persistent enough that they could be diagnosed with a condition like major depressive disorder, versus those who might simply be reporting (temporary) mental health symptoms caused by the shock and disruption of COVID-19. Nonetheless, this survey received a total of 8.7 million unique responses between April 6 and September 1. As such, it can provide some very important information about everyday experience in response to COVID-19. Such a wealth of data demands our attention.

Some very important information about everyday experience in response to COVID-19

The Carnegie Mellon/Facebook survey data are reinforced by recent peer-reviewed research from around the world. A study published in Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior [PDF] by a team from University of Arkansas-Fayetteville found since the beginning of the pandemic suicidality among vulnerable U.S. populations has increased. They found that Black and Latinx people, females, and those who are younger appeared to be acutely at risk" for increased suicidality as a result of the pandemic (note that the data the paper relied on was gathered in March 2020, and it was written prior to the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the protests that followed). Indeed, per the Carnegie Mellon/Facebook survey, 18.6 percent of females aged 18–24 reported recently being depressed most of the time in April.

Meanwhile, a May 2020 Psychiatry Research [PDF] paper on projected increases in the Canadian suicide rate as a result of COVID-19 concludes that the researchers' analysis—which examines the relationship between increases in the unemployment rate and suicide—underscores the urgency of prioritizing access to mental health care and providing "psychological first aid." Finally, a Community Mental Health study published in June examined the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns across society in India. The researchers found higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety among respondents under lockdown without daily essentials, adding that "students and health professionals need special attention because of their higher psychological distress."

"Practitioners should be prepared for what will likely be a significant mental health fall-out in the months and years ahead," the University of Arkansas researchers noted in their paper.

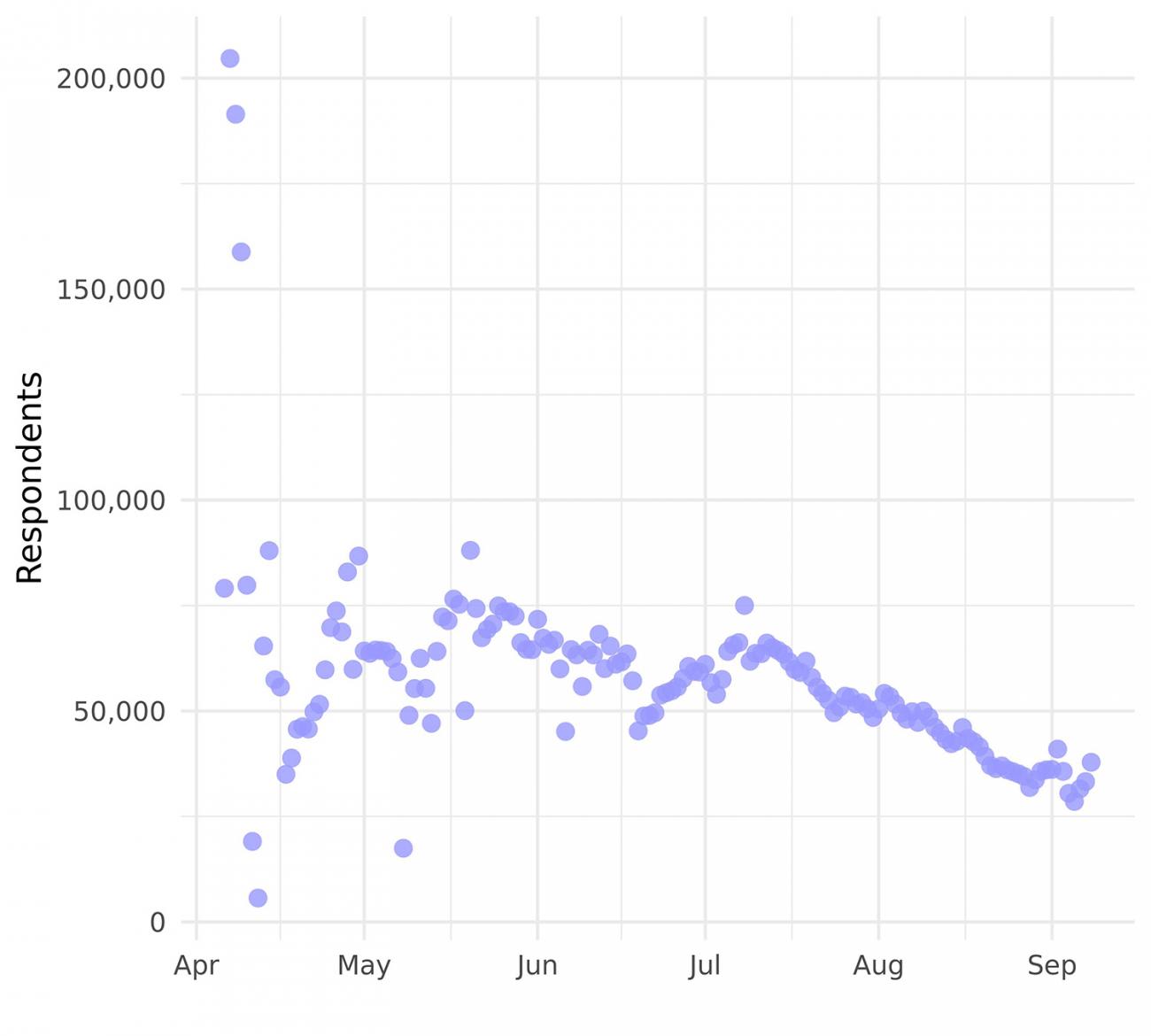

Tens of Thousands Facebook Users Responded Every Day

Given the size of Facebook's audience—1.79 billion daily active users in the second quarter of 2020—it's no surprise that the Carnegie Mellon/Facebook COVID-19 survey cast a wide net. But the survey's sample size remains staggering—it produced a lot of data. The figure below shows U.S. survey responses by date. Though the daily average was 59,000 responses, peaks of 204,000, 191,000, and 159,000 were seen in early April—just when the United States was gripped by the early stages of the pandemic.

But as noted, because the survey was only taken by Facebook users its respondents may not be representative of the general population.

Depression symptoms in the United States are more than three-fold higher during COVID-19 than before the pandemic

Examples of work representative of the general population include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Household Pulse Survey and a September JAMA study on symptoms of depression before and during the pandemic. The latter's participants represent a cross section of U.S. adults (across age groups and racial groups), and the study's findings suggest the prevalence of depression symptoms in the United States was "more than three-fold higher during COVID-19" compared to before the pandemic. Overall, the Carnegie Mellon/Facebook survey "may contribute to a better public health understanding of where the coronavirus pandemic is moving, to improve our local and national responses," wrote the researchers who analyzed the survey.

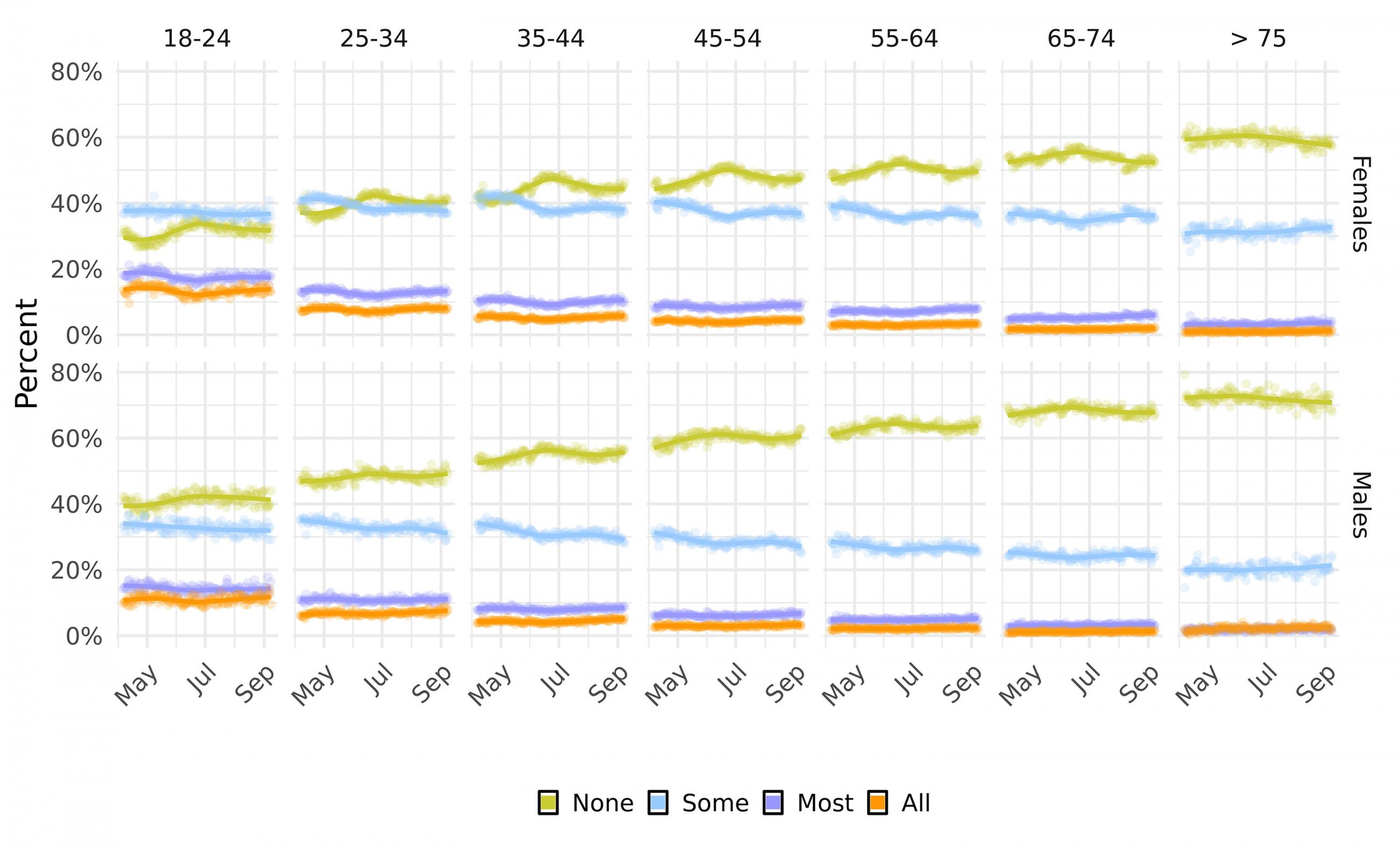

A Progression in Anxiety

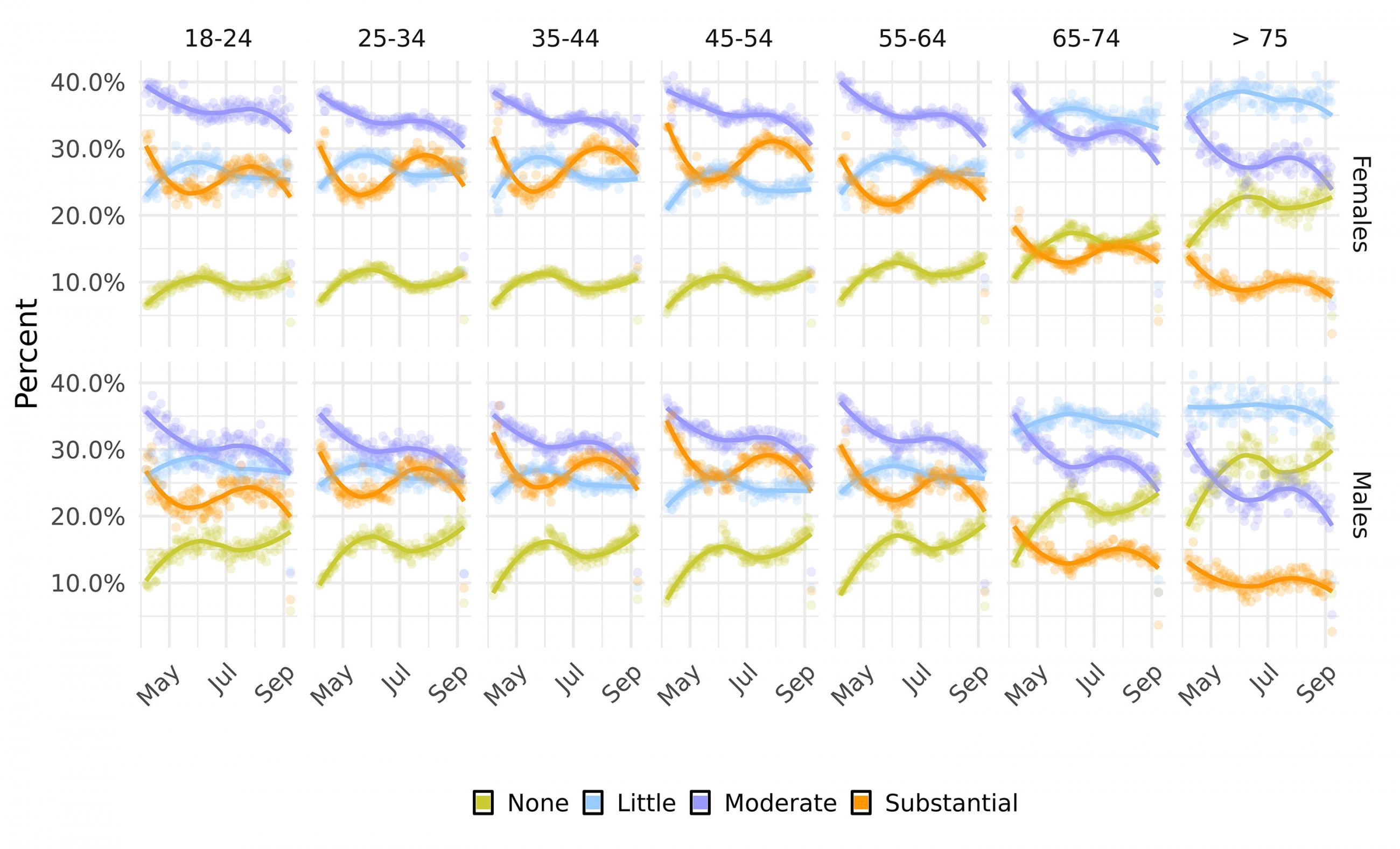

In addition to depression, the Carnegie Mellon/Facebook survey also covers anxiety. The figure below shows the percentage of survey respondents who reported how often they felt anxious, by sex and age group. The data illustrate how different age groups and sexes have been responding to the pandemic. Broadly, younger people and females report being anxious "all of the time" or "most of the time" more often than do older respondents and males.

Anxiety data show a progression in older populations over the course of the pandemic

Additionally, the anxiety data show a progression in older populations over the course of the pandemic, perhaps indicating how we've learned to live with it (or because lockdowns were lifted). For example, in April 40.4 percent of males aged 45–54 reported feeling anxious some of the time and 46 percent reported feeling anxious none of the time. By August, the situation had changed: only 33.9 percent of males aged 45–54 reported feeling anxious some of the time, and 53.7 percent reported feeling anxious none of the time.

Often tied to anxiety levels are one's finances, particularly when money is tight. The survey includes questions related to COVID-19's effect on household finances, specifically the degree to which respondents see COVID-19 as a threat to their personal finances.

Similar to anxiety, the data indicate a telling (if not necessarily surprising) split between younger and older respondents and males and females. Looking at the percentage of females who reported in August 2020 that COVID-19 represented a "substantial" threat to their household finances suggests that older populations have been weathering the pandemic's financial storm better than younger populations.

The Carnegie Mellon/Facebook data reinforce what we already know—or at least suspect—anecdotally: that COVID-19 has had a marked impact on mental health. After all, beginning or ending emails and Zoom calls with some variation of "hope you're well" has become second nature. The question then is not whether COVID-19 will impact mental health but how broadly and how severely.

Rising Attention to the Problem

The good news is that the topic of mental health is being given increased attention, even in the midst of everything else that 2020 has brought with it. For example, on September 29 alone a number of major media outlets in the United States (NBC, CBS Baltimore, Yahoo! Finance) all published articles related to mental health during the pandemic.

And a U.S.-specific Google news search for "mental health COVID" between January 1 and June 30, 2020 turns up about 18.9 million results. But a search for the same term during a much shorter but more recent time period—July 1 and September 30—finds 27.9 million results. Likewise, searching the National Library of Medicine's PubMed database for the same phrase turns up more than 2,500 studies, reviews, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews; more than 2,000 of which have been added to PubMed since June 1.

Growing interest in the media, the medical community, and in society for quantifying how COVID-19 is affecting mental health

Those anecdotes, plus data from sources like the Carnegie Mellon/Facebook survey and peer-reviewed research, point to a clear trend: there is growing interest in the media, among the medical and scientific communities, and broadly in society, in quantifying how COVID-19 is affecting mental health outcomes. We're worried, as we probably should be. How we respond—both now, while we're still grappling with the pandemic, and once COVID-19 is past us—will determine whether COVID-19 leads to setbacks in the fight against mental disorders, or if we can find a way to use the widespread, broadly acknowledged disruption caused by COVID-19 to improve mental health outcomes around the world—and address some of what Shakespeare called the heartache and the thousand natural shocks / that flesh is heir to.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors are employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which produced the COVID-19 forecasts described in this article. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.