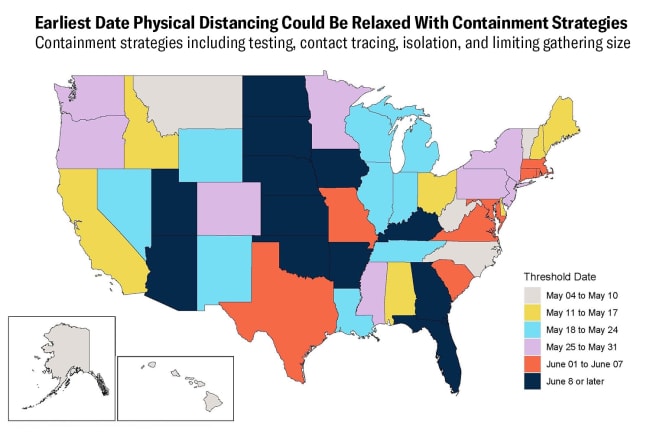

As the beginning of the school year falls upon us in the United States, education during the pandemic is looking like a lose-lose situation. The COVID-19 predictions are worsening: during the fall and winter, the risk of transmission is expected to double, with deaths approaching the 300,000 mark by December 1 according to the latest forecasts by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, where the three of us work. Nearly half of U.S. states are likely to need to lockdown again this fall to avoid a surge of COVID-19 patients in their hospitals.

Understanding how forgoing in-person school could affect students has taken on new importance

Keeping children and staff safe in a school setting seems less and less feasible, yet the consequences of not opening schools are stark, especially for the most vulnerable children. For many children, lack of school may translate to falling behind academically, food insecurity, and/or increased risk of falling victim to domestic violence. As many schools choose to start the year online or via a hybrid model—according to data from roughly half of the country's districts—understanding how forgoing in-person school could affect students has taken on new importance. Yet COVID-19 cases in children have been rising, and a recent JAMA study suggests kids, in particular those five and under, could drive the spread of the pandemic.

So should the kids go, or not go, to school? Either way, will they be alright? Will we as a society be alright if they go or don't go? Let's say schools do reopen (as those in New York plan to, for example): what could that mean for school staff and for those people the staff come into contact with? Finally, what are some ramifications of not sending children back to school? How, for example, will children dependent on school meals for nutrition fare if schools are closed this fall (and longer)? What will caregivers who are unable to work from home—and who may need to work in order to provide for their children—do if schools don't reopen?

To answer these questions, we looked at evidence from four states taking different approaches to the question of reopening schools this fall—Vermont, Florida, Georgia, and IHME's home state of Washington.

Vermont, Florida, Georgia, Washington: A Tale of Four Policies

Vermont, Florida, Georgia, and Washington present four approaches to the question of how to reopen schools this fall, if at all. While Vermont and Florida have thus far opted to emphasize in-classroom learning, Georgia and Washington are taking localized approaches, allowing each school district to decide. This could well mean that some school districts in both states will be fully remote while others opt for hybrid—partly at home, partly in school—models.

Risk is dependent on the degree to which the virus is present in communities

A risk of increased infection is inherent to any approach involving in-person interaction, but that's dependent on the degree to which the virus is present in communities. According to IHME estimates, as of August 20, Vermont had the lowest infection rate in the country at an estimated mean of 1 per hundred thousand. Full in-person school in Vermont is therefore a less risky proposition than in Georgia, where the infection rate on August 20 was an estimated 82 per hundred thousand. The table below shows the total number of estimated deaths and infections on August 20 and December 1 in each state (plus overall US numbers), as well as mask usage in each state and the United States on August 20.

Estimated Deaths, Infections, and Mask Usage in Four States

The scope of COVID-19 outbreaks for four states and U.S. overall on August 20 and December 1, 2020

EDITOR'S NOTE: Sources for the table above include IHME, Premise, Facebook Global Symptom Survey (research based on survey results from the University of Maryland Social Data Science Center), Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), and YouGov.

How closely children can and will observe those guidelines remains a matter of speculation

Mask usage and social distancing (in the classroom or otherwise) can mitigate the chance of infection. Though Vermont and Washington have mandated that people wear masks or other face coverings in public spaces and businesses, Georgia and Florida have not: both states currently recommend masks without mandating them. While all four states have recommended social distancing guidelines—Georgia's guidance advises residents to "stay at least six feet apart" and "limit your outings"—how closely children can and will observe those guidelines remains a matter of speculation.

Underscoring this worry is the recent Washington Post piece about the COVID-19 outbreak at a summer camp in Georgia. The Post notes that "some 260 campers and staff tested positive out of 344 test results available. Among those ages 6–10, 51 percent got the virus; among 11–17 year olds, 44 percent; and among 18–21 years old, 33 percent. The campers did a lot of singing and shouting and did not wear face masks, and windows were not opened for ventilation, although other precautions were taken. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) concluded that the virus "spread efficiently in a youth-centric overnight setting, resulting in high attack rates among persons in all age groups," many showing no symptoms."

260 campers and staff tested positive out of 344 test results available at one summer camp in Georgia

Thankfully, we know that there is a low risk of bad outcomes from COVID-19 in children. However, there is a risk of serious multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Also, infants' risk of dying from COVID-19 is higher than it is for older children—children under the age of one have a risk of dying from COVID-19 that is similar to that of 30-year-olds. In the United States, per CDC data on COVID-19 deaths by age, between February 1 and July 25, 2020, there were only forty-five COVID-19 deaths in children aged fourteen and under. But just because we haven't seen widespread death in children due to COVID-19, that doesn't mean kids can't become infected with the coronavirus, carry it asymptomatically or have mild symptoms only, and transmit the virus to others.

Infections in teachers and other school employees are a concern. In Georgia's largest school district, for example, teachers returned to work on July 29 to begin planning for the school year. The following day, 260 school employees were in quarantine. There are more than 100,000 teachers in Georgia and more than 150,000 in Florida, who are placed at risk by sending children back to school in the fall. Even if children (of whom there are more than 40 million between the ages of five and fourteen in the United States, according to Census data) don't get sick, some school staff certainly will. And so could the staff's families, plus anyone they might interact with in poorly ventilated interior spaces.

What about the other option? After all, there could be real ramifications to closing schools, even partially. Could keeping children home from school to prevent the spread of COVID-19 do as much harm (or at least different harm) as good?

Breakfast, Lunch, Economics, and Disparities

To start, there's breakfast and lunch. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) national school breakfast and lunch programs provide vital nutrition for tens of millions of children each year. When children are fed through programs like these, their families are helped financially don't need to provide lunch for them. Moreover, USDA's free meal programs provide a literal lifeline to children experiencing homelessness, for whom school can be a sanctuary.

What are hourly and essential workers supposed to do if schools close?

Then there are the other economic implications related to closing schools, aside from free meals. Across the country, more than fifty million people have filed for unemployment since the start of the pandemic. And per 2019 Bureau of Labor statistics estimates, there are millions of workers in the United States for whom working from home (and keeping an eye on one's distance-learning children) isn't an option, both because their work necessitates being out of the house, and because they have to work to make ends meet: 3 million registered nurses, almost 700,000 electricians, 2.1 million janitors and cleaners, and 3.3 million cooks of all stripes, to name a few, find themselves in these challenging circumstances. What are hourly and essential workers supposed to do if schools close? The health system may also suffer shortages since women make up 76 percent of the health-care workforce, and disproportionately shoulder a greater share of childcare.

Finally, there's the question of whether the great societal experiment forced on the world by COVID-19—whether we can successfully shift to working and learning remotely—will work. Though working from home has proved to be a success in some ways, the jury's still out on distance learning—especially elementary school distance learning.

Black, indigenous, and people of color have also been hit harder by the economic and health impacts of the pandemic

Online learning seems to be widening disparities in education. For example, the Los Angeles Unified School District found that students who were Black, Latinx, non-native English speakers, disabled, low-income, experiencing homelessness, or in foster care were unable to participate in online learning at the same rates as their peers. Many of these children and their families experience systemic racism and discrimination. Caregivers who identify as Black, indigenous, and people of color are disproportionately represented among essential and low-wage workers, posing challenges for supervising their children's learning and affording childcare. Black, indigenous, and people of color families have also been hit harder by the economic and health impacts of the pandemic compared to white families due to long-standing inequities driven by systemic racism. Disparities also stem from lack of internet and access to laptops or tablets, which many districts, including the Los Angeles and Philadelphia school districts, have attempted to address by providing free computers and WiFi hotspots.

Efforts to identify pandemic-friendly education are taking shape. Increasingly, affluent families are hiring private tutors and forming "learning pods" with other families, which is likely to widen educational disparities (there are also reports of some parents seeking out private schools for in-person instruction). What is the potential for more equitable innovation within the public school system? Some are advocating for moving school outdoors to lower the risk of infection. According to the New York Times, this practice was adopted in New York City in the early 1900s to reduce the spread of tuberculosis. As many restaurants have expanded outdoor dining on to the street, could classrooms follow suit? School districts in Seattle, Massachusetts, and Detroit are considering it.

The available evidence suggests there is no easy answer

With no quick end to the pandemic in sight, there is an urgent need to develop safer alternatives to school as we know it. The broader our evidence base, the better we can understand how to approach issues like schooling during COVID-19. Regardless of the direction decision-makers choose to go in for school this year, the available evidence suggests there is no easy answer. Even as our scientific understanding of COVID-19 and its impact on children advances, it is challenging to weigh the pros and cons when it comes to education. This is all the more reason for policymakers to ensure that all children are given equitable educational opportunities both now during COVID-19 and once the pandemic has passed.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The authors are employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which produced the COVID-19 forecasts described in this article. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.