Until an effective COVID-19 vaccine is produced at a scale needed to immunize the majority of the population, tens of millions of Americans will be vulnerable to severe infection. This includes the elderly as well as working-age adults with chronic health conditions. Those populations together make up roughly 25 percent of all Americans. As COVID-19 deaths and cases decrease in the United States, policymakers will have to make difficult decisions about how to safely open our country. Some states are already beginning to lift restrictions on public gatherings and business closures. Understanding and defining the populations at high risk for severe COVID-19 infection will be essential for protecting the health and well-being of all Americans.

The elderly, and especially those with underlying diseases, will continue to be most vulnerable Americans to COVID-19

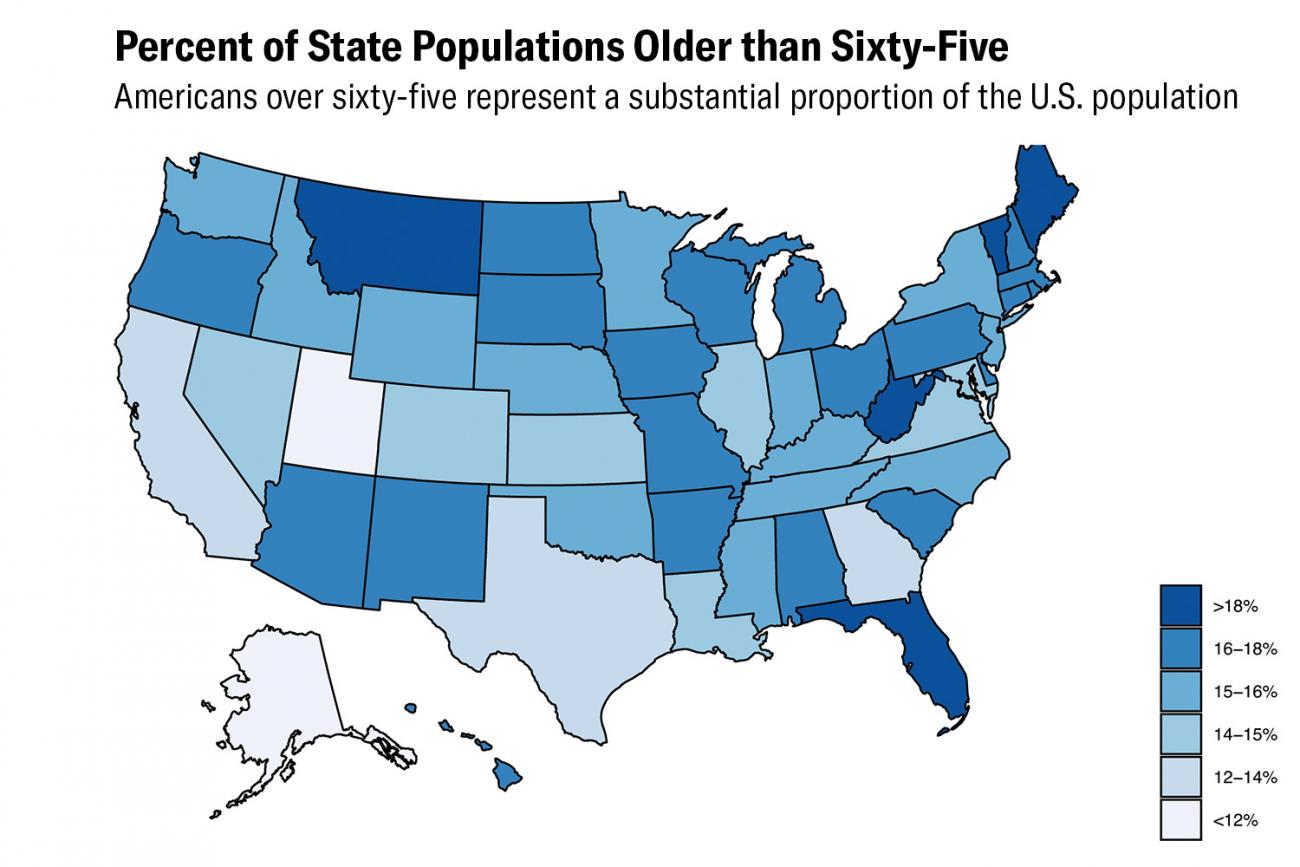

Evidence from the United States and elsewhere indicates that cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and old age are influential risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection. Perhaps the most frequently cited risk factor is old age. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) released data indicating that more than 75 percent of COVID-19 deaths were among adults over 65 years old. As it turns out, about 15 percent of Americans (49.9 million people) are older than 65. Moreover, the incidence of chronic diseases that put people at higher risk of severe COVID-19 infection tends to increase with age. More than 22 million Americans over 65 have cardiovascular disease (44.6 percent), about 14 million have chronic respiratory disease (28.2 percent), and 13.9 million have diabetes (27.9 percent). The elderly, and especially those with underlying diseases, will continue to be most vulnerable Americans to COVID-19. Does that mean that the rest of the American working-age population is at low risk and could be able to return to work and relatively normal life in a month or two? Probably not.

For starters, severe and fatal COVID-19 infections have occurred in all ages and among otherwise healthy adults with no underlying medical conditions. Still, it is useful to know which adults are most likely to have severe infections.

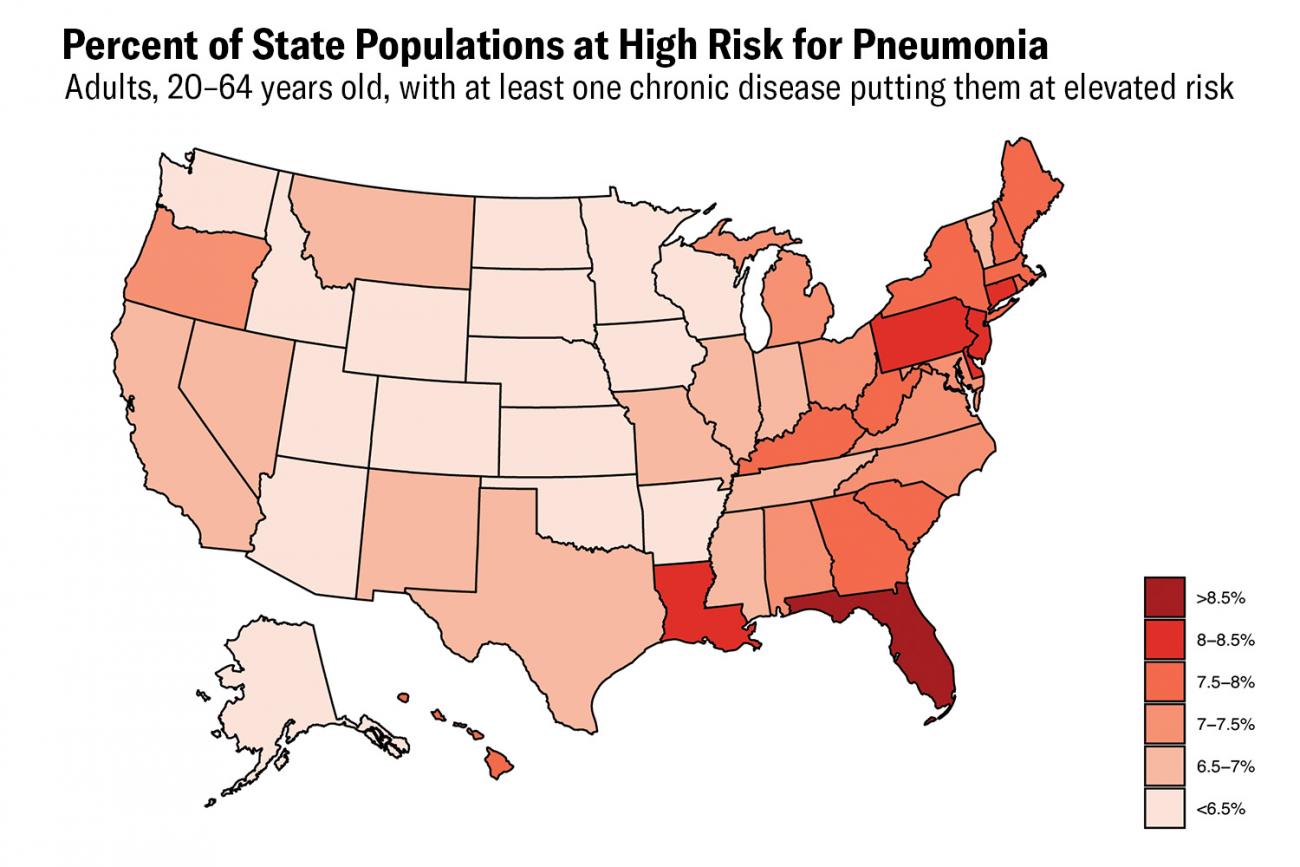

About 7 percent of Americans age 20–64—13,800,000 people—live with conditions that put them at high risk for pneumonia

One approach to defining a high-risk population could be to apply the CDC recommendations on the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. This vaccine protects against the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae, the leading cause of pneumonia mortality in the United States and around the globe. It could be reasonable to assume Americans at risk for bacterial pneumonia could also be at risk for pneumonia more generally, including COVID-19. In fact, many of the underlying conditions that predispose people to severe COVID-19 infection are also relevant to bacterial pneumonia. The CDC recommends pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for all adults over sixty-five and for certain high-risk adults nineteen to sixty-four years old. According to current recommendations, working-age adults (defined here as those nineteen to sixty-four) with hemoglobinopathies (such as sickle cell disease), HIV infections, chronic kidney disease (advanced stages), leukemia, lymphoma, and other metastatic malignancies (cancers), among several other conditions, should be vaccinated with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Estimates from the 2017 Global Burden of Disease study suggest that about 13,800,000 Americans ages twenty to sixty-four live with these conditions, representing about 7 percent of the population in this age group.

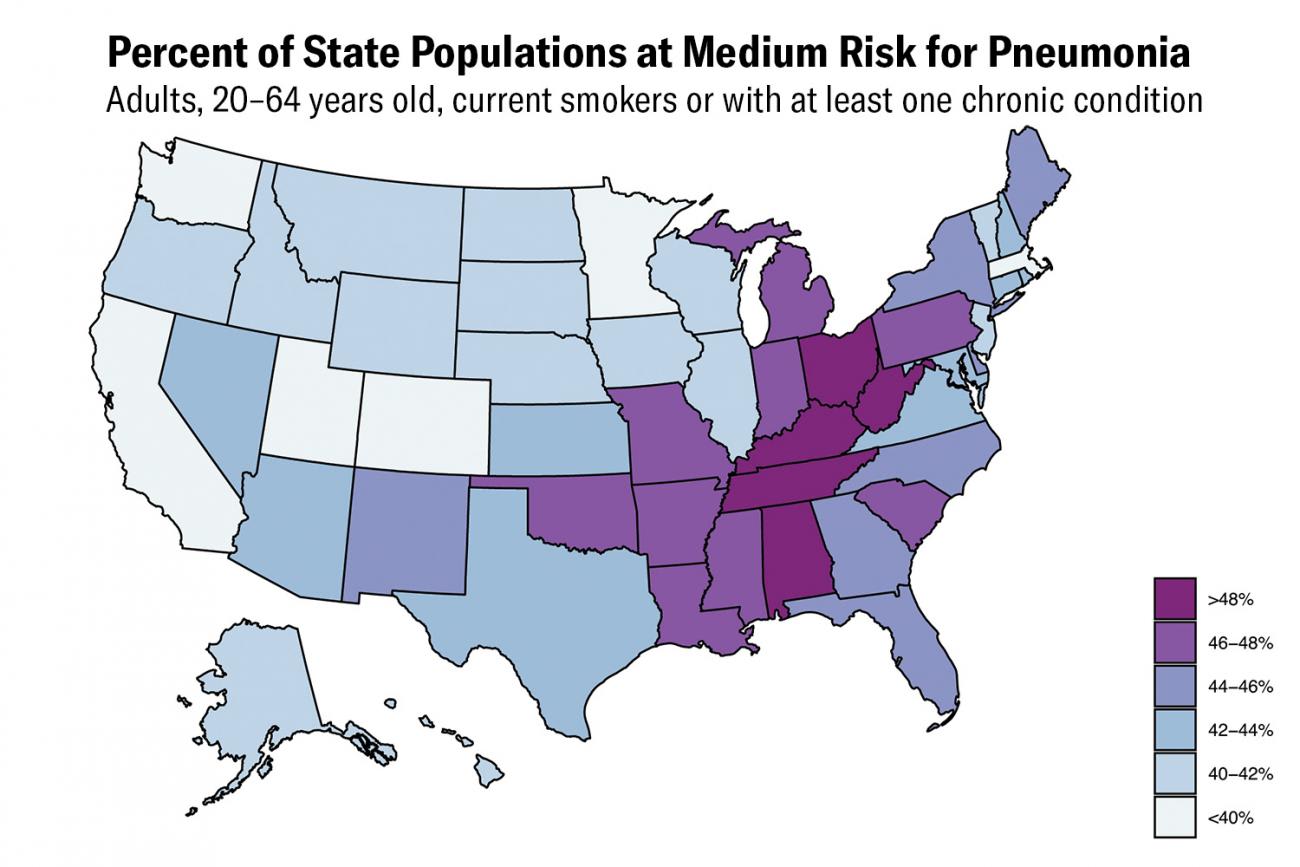

Furthermore, the CDC recommends that adults ages nineteen to sixty-four who smoke or suffer from alcoholism, diabetes, or chronic heart, liver, or lung disease be vaccinated with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. A further sixty-three million Americans with asthma, cirrhosis, diabetes, or chronic respiratory disease are in that age group.

Although these estimates are independent, and some Americans with multiple diseases are considered here, this group of people makes up about 32 percent of the population in the 19 to 64 age group. Finally, an estimated 30.7 million smokers are in that age group, roughly 16 percent of that population. In total, including those with underlying medical conditions and current smokers, this group is about 43.5 percent of the population 20–64 years old, or 83.4 million Americans.

A recent analysis (submitted for peer review) from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine sought to estimate the global population of working-age adults fifteen to sixty-four years old with medical conditions that make them particularly vulnerable. Using a similar approach (i.e., attempting to quantify the prevalence of relevant underlying diseases among the adult population), the analysis found that approximately one-fifth of all adults worldwide would be at high risk. Countries that have completed the epidemiological transition—the shift from infectious diseases to chronic diseases as the primary disease burden—tend to have a larger share of the population at high risk (16 percent in sub-Saharan Africa vs. 31 percent in Europe).

Changes in personal and social behavior and norms could be required for months or years and we collectively must take those steps

The study proposes an idea of shielding, defined as "a measure to protect extremely vulnerable people by minimizing interaction between those who are vulnerable and others." Potential methods of shielding include alerting those at particularly high risk of their status and encouraging them to practice social distancing indefinitely, establish an isolated area of their homes, plan for contactless delivery of food and medical supplies, use face masks whenever outside the home, and plan for provision of care and treatment if they do get sick. These lifestyle changes will be difficult, particularly for low-income adults and adults in countries with fewer medical resources. These high-risk people could also be prioritized, along with healthcare workers, for any eventual vaccine against COVID-19.

Depending on what characteristics are used to define high and medium risk, tens of millions of Americans are high risk for severe COVID-19 infection. A clear picture of who these people are and where they live can help policy makers and public health officials design policies to limit the exposure to this virus, especially high-risk people. Changes in personal and social behavior and norms could be required for months or years and we collectively must take those steps to help protect the most vulnerable people in our communities.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The author is employed by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which leads the Global Burden of Disease Study and the COVID-19 research mentioned in the post. IHME collaborates with the Council on Foreign Relations on Think Global Health. All statements and views expressed in this article are solely those of the individual author and are not necessarily shared by their institution.