With many states still on lockdown and school districts across America actively debating how to reopen in the fall, many questions abound. When will things return to normal? When will we cease to fear exposure to this insidious virus? When will we give up our masks, stop hoarding toilet paper, and start to stand less than six feet apart?

History is dotted with moments in the past where people facing other diseases were gripped with similar questions, some of which mirror aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

One disease worth remembering for that reason is the tidal wave of virus that swamped New Orleans, much of the south, and other parts of the United States throughout the nineteenth century—yellow fever.

Midway through his first term as U.S. President, Thomas Jefferson wanted a treaty with France that would allow the United States free passage through the Ohio valley, across the Mississippi river, and to points further west. So in 1803 he dispatched James Monroe—who later served two terms as president himself—to Paris. There, Monroe was to negotiate with Napoleon Bonaparte and his representatives. Would France consider granting such rights of passage? Better yet, could the United States purchase a piece of France's massive territory—a small part of Florida perhaps?

More than 41,000 people died from yellow fever in New Orleans throughout the nineteenth century

What Monroe negotiated instead, far exceeding his mandate, was the Louisiana Purchase—buying the whole of France's territory in North America, approximately 827,000 square miles of land, for $15 million (just over $340 million today)—including the city of New Orleans, an important commerce city considered to be the jewel of the territory. Following Monroe's transaction, opportunity seekers flooded into New Orleans, its population exploded, and it became the second most popular U.S. destination for immigrants after New York City. But many of the newcomers when they arrived found only viral disease and death. Over the next century, more than 41,000 people died from yellow fever in the city.

The 1878 yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans was by no means the worst outbreak the city had ever seen. Nor was it the last. But it was huge and devastating, impacting the entire region and inflicting massive economic losses. There are a lot of parallels with COVID-19 in that alone.

But what is most illuminating to us about the New Orleans yellow fever outbreak of 1878 is the question of when things return to normal after an epidemic. The lesson of that particular plague is that sometimes they never really do.

A Strange and Frightening Disease

To the nineteenth century imagination, yellow fever was a strange, frightening disease. Nobody understood how it was transmitted except to say one sick person somehow infected others.

At the time, the (incorrect) prevailing theory was that it spread like smallpox—through infected clothing, blankets, and other "fomite" objects or surfaces. But it was hard to make sense of other perplexing aspects of the disease, such as its transmission pattern.

Yellow fever was mostly endemic to urban areas. It did appear in rural areas, but was much less common there [PDF]. Cases occurred annually, and serious outbreaks happened every few years, but in a seemingly random and unpredictable way. During some decades in the 1800s New Orleans had multiple major outbreaks—in others, none. Its seasonality, on the other hand, was like clockwork, hitting New Orleans in the summertime and disappearing in the fall.

If what they didn't know about the disease bothered them, what they did know terrified them

At the time, nobody could explain this seasonal pattern or why the virus struck cities worse than rural areas. But if what they didn't know about the disease bothered them, what they did know terrified them. Yellow fever was universally feared throughout the south in the 1800s because it caused severe malaise, a frightening jaundice, turning the eyes and the skin yellow, it filled the stomach with black bile, and it killed in troves. So serious was the threat of yellow fever in those days that life insurance policies in the nineteenth century often contained language that voided payouts to anyone who travelled through yellow fever country in the south.

In major outbreaks, thousands of people would die, businesses would be devastated, and the "saffron scourge," as yellow fever has sometimes been called, could kill up to a third of the population in some neighborhoods. During the summer months throughout the nineteenth century, residents of New Orleans would routinely retreat from the city to plantations or rural homes.

Plague Ships and Shotgun Quarantines

In 1878, several years had passed without a major outbreak of yellow fever, but that year the disease struck New Orleans with vengeance. In June, 1878, the steamship Emily Souder had stopped off in Cuba on its way to New Orleans, and when it docked in the city, people started dying.

Deaths From Yellow Fever in New Orleans in the 1800s

Major outbreaks of the viral disease occurred frequently in the nineteenth century

The outbreak quickly exploded and grew to become one of the most expensive epidemics in American history. It cost the local economy at least $100 million (more than $2 billion in today's dollars)—more than the entire Louisiana Purchase itself—and the human toll was even more devastating. By the time the outbreak dissipated, some twenty thousand people died, and fatalities were recorded from Florida to Arkansas and from New Orleans to New York. A quarter of the deaths occurred in New Orleans.

The outbreak became one of the most expensive in American history

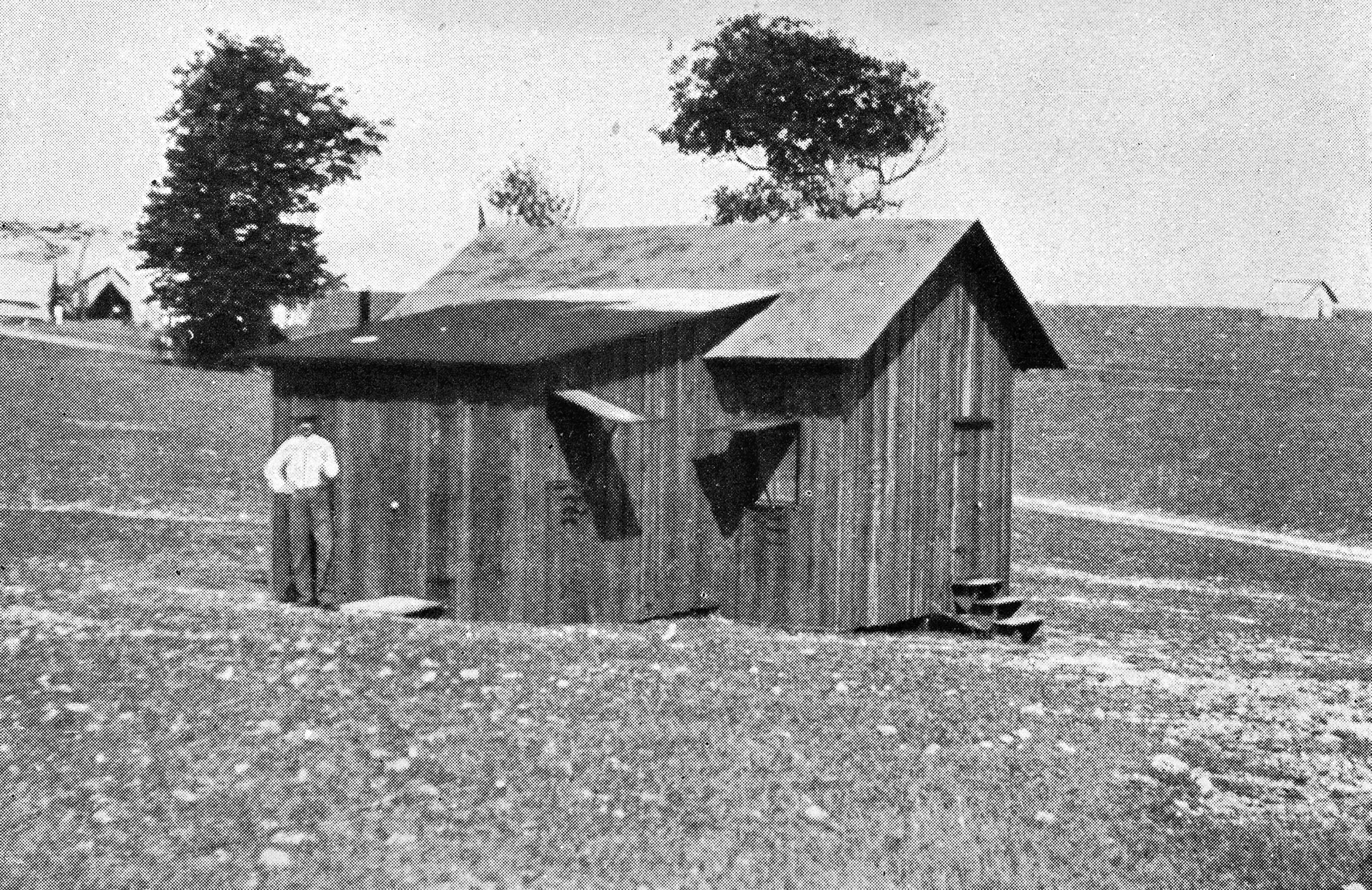

Several aspects of the 1878 outbreak mirror episodes in the COVID-19 pandemic. One was when cruise ships were feared floating incubators of coronavirus and forbidden to dock at ports. The famous plague ship of 1878 was not a grand ocean vessel like the Diamond Princess, but a much more humble riverboat steamer named the John D. Porter. It set out from Memphis, Tennessee, carrying passengers desperate to flee the city, only to be turned away from each port upriver from Memphis by authorities who feared it harbored the disease itself.

Like New Orleans, Memphis was particularly hard hit in 1878, and as was the practice at the time, those who could afford to escape the city did, and in 1878, fully half the city's population fled. Of the 19,000 people who stayed, 17,000 contracted the disease, and more than 5,000 died.

Of the 19,000 people who stayed in Memphis, 17,000 contracted the disease, and more than 5,000 died

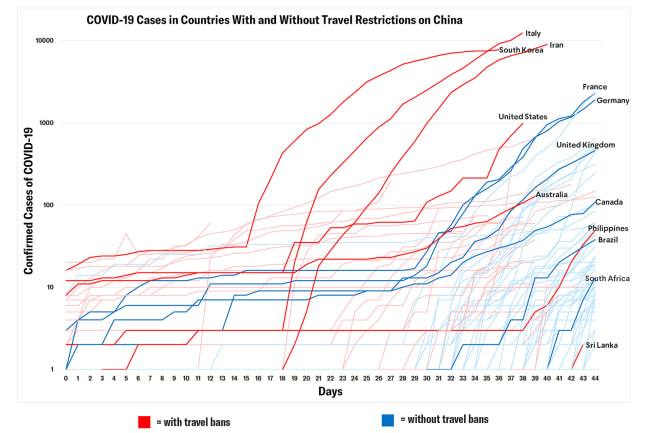

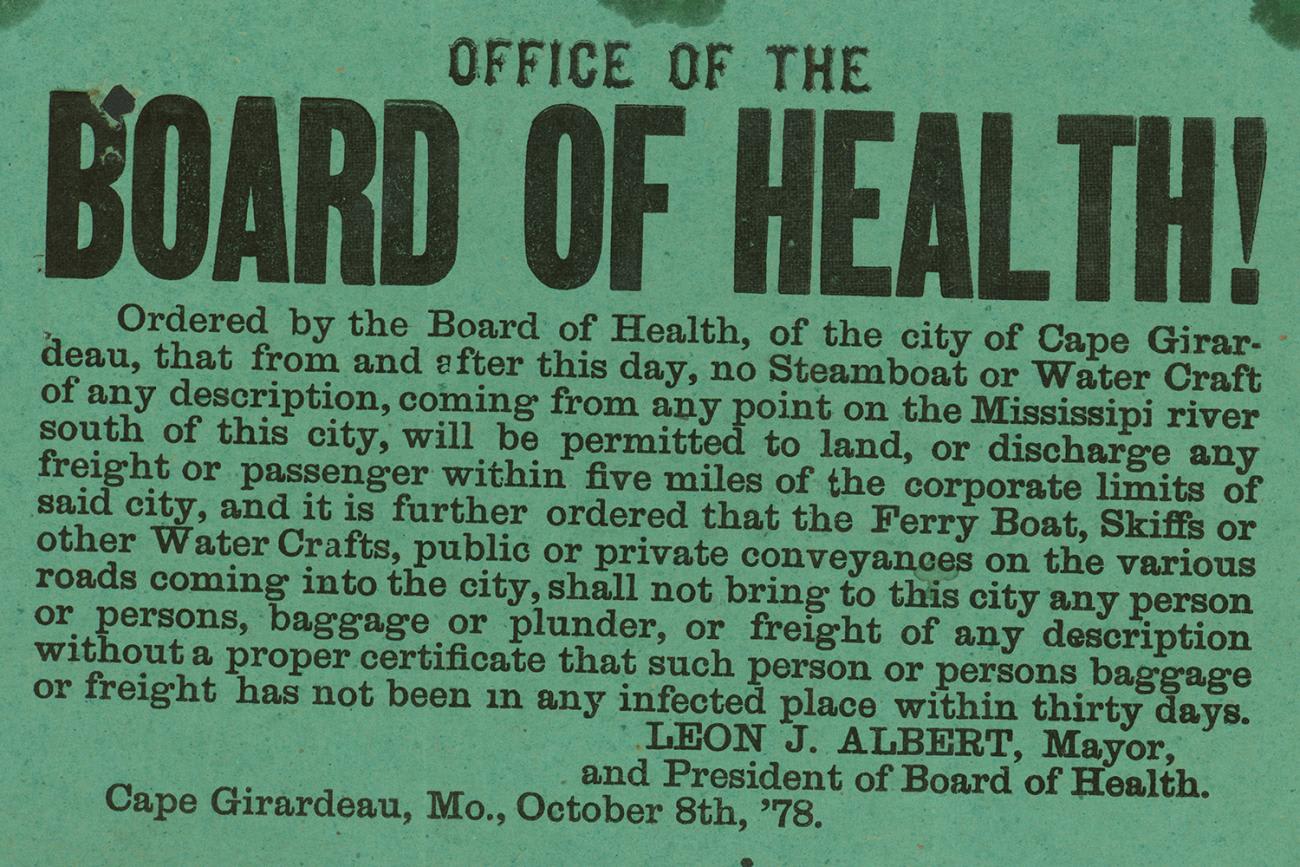

The experience of those ill-fated passengers aboard the John D. Porter was not unique and is another reminder of the response to coronavirus. Containment and quarantine was a common way of dealing with yellow fever everywhere it struck, from the coast of Australia to the islands of the West Indies. In 1878, the U.S. government passed federal quarantine laws—but by then many states, cities, and towns bent on self-preservation were already vigorously pursuing their own travel bans. For the remainder of the century, patchwork travel restrictions became commonplace in the south, and they took on a particularly American flavor.

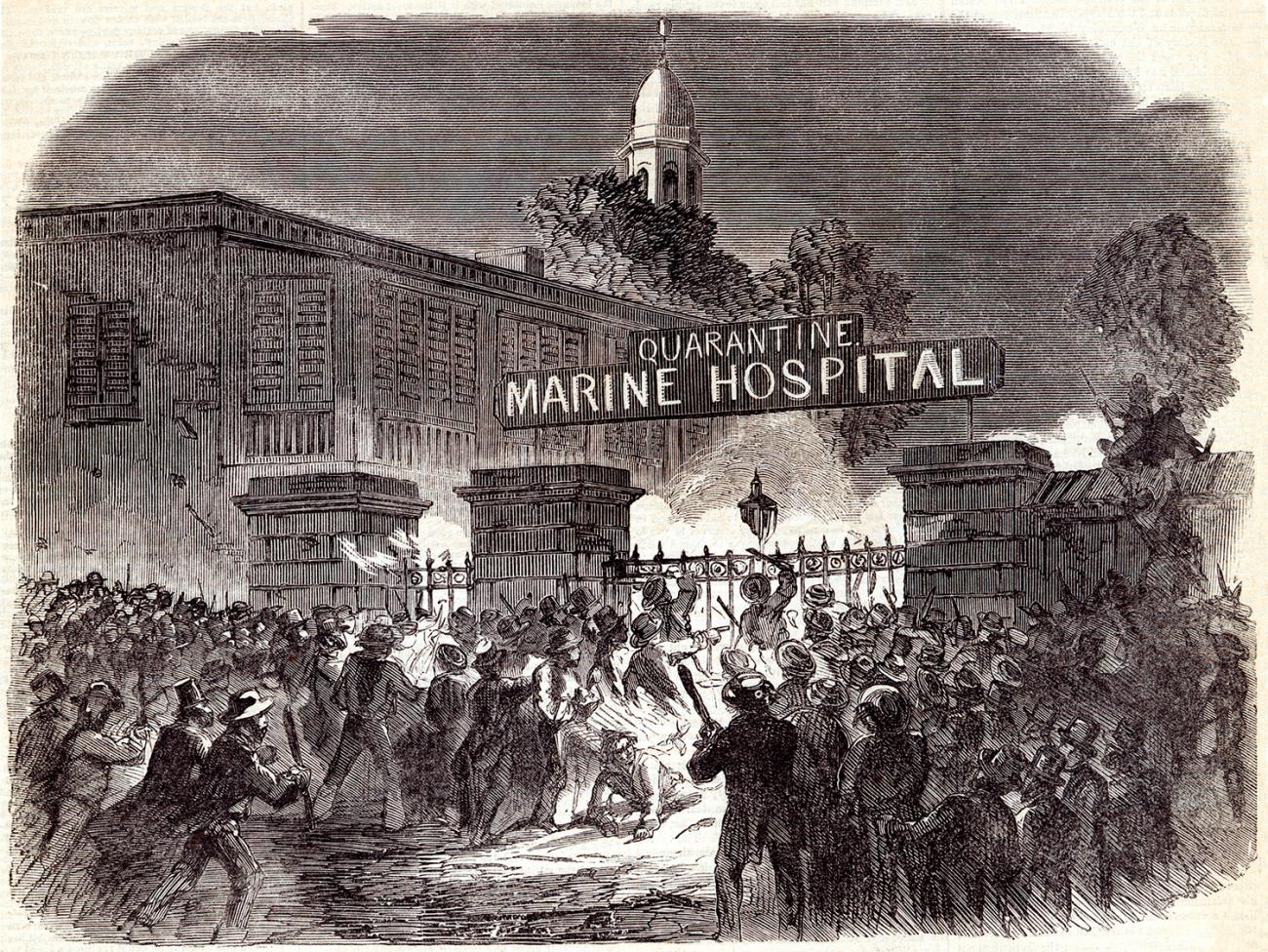

Dubbed "shotgun quarantines" in Chicago Daily Tribune and Washington Post headlines, the new American travel restrictions were generally characterized by two things: prohibitions on all people from entering or leaving an area and armed mobs of deputized enforcers maintaining these cordons sanitaire with the business ends of their scatterguns.

The Lasting Impact of the 1878 New Orleans Yellow Fever Outbreak

The legacy of the 1878 yellow fever epidemic was that it led to health and sanitation reforms, spurred legislation, launched major lawsuits over the legality of quarantines, and started a scientific race to better understand the disease and how to treat it.

The outbreak may have helped lead to the concept of public responsibility for community health—an idea we continue to struggle with today in the debates over bans on public gatherings and mask wearing requirements. It also led to arguments over whether the economic fallout of the commercial shutdowns was worse than the human toll of the disease itself—an issue also hotly debated today with COVID-19.

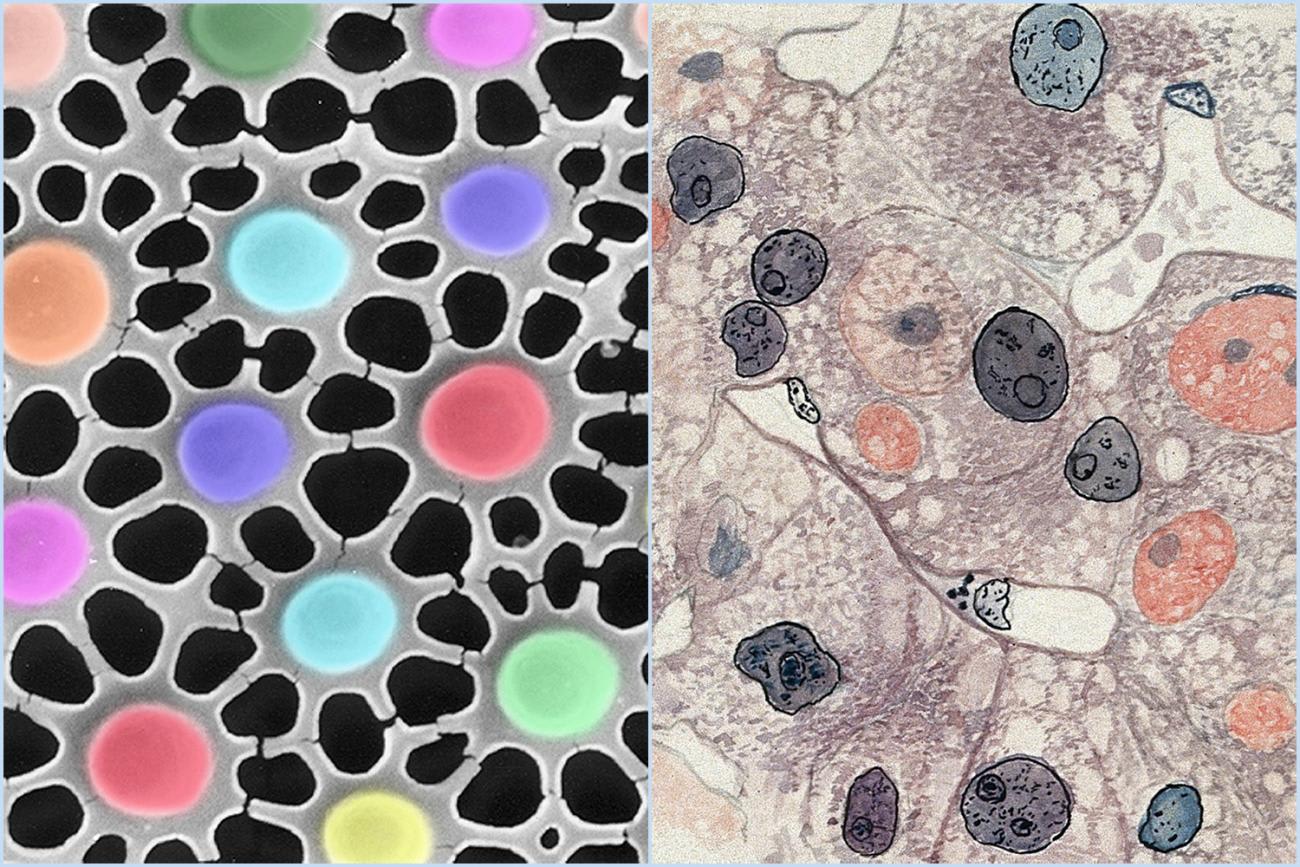

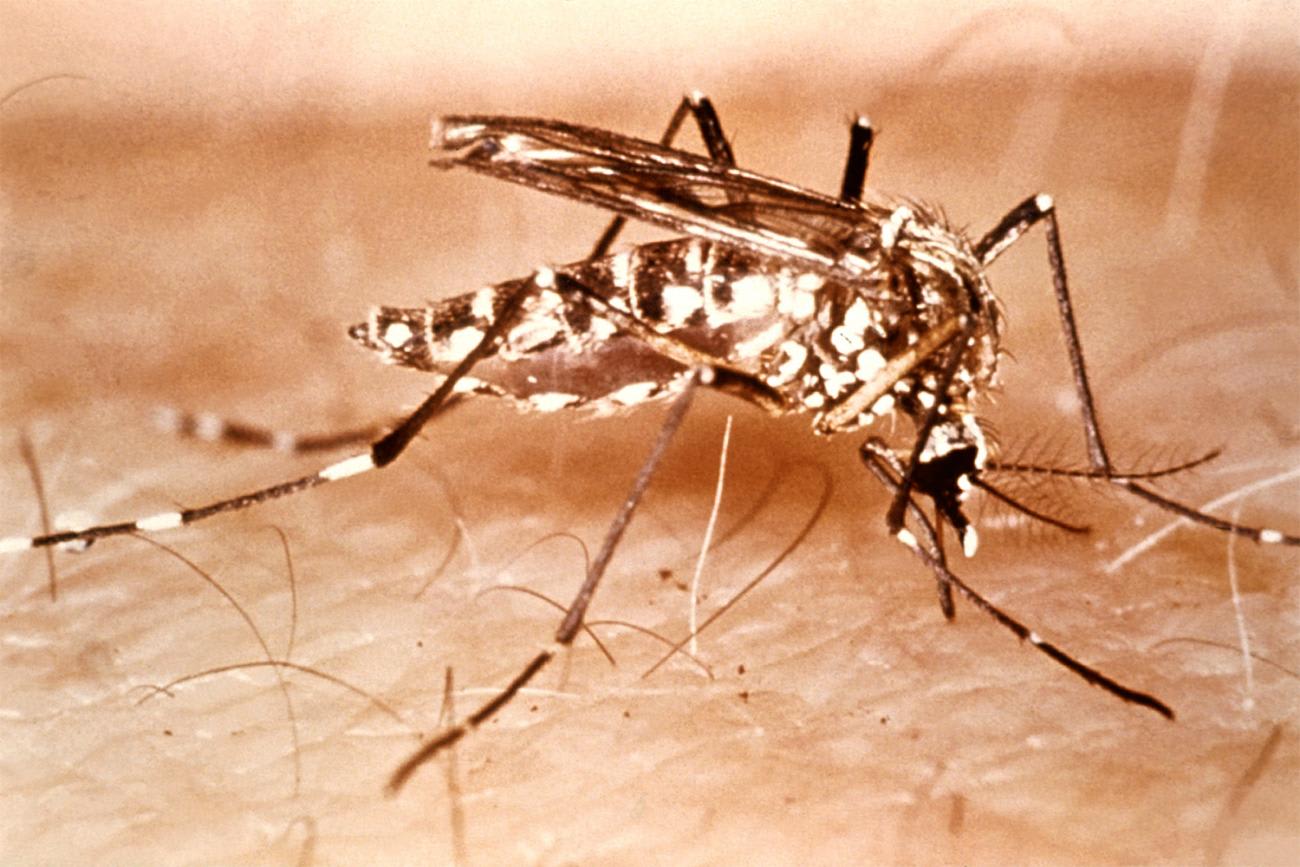

Walter Reed and his team discovered that the Aedes aegypti mosquito was the culprit

But in the end, perhaps the most hopeful parallel from yellow fever may be its last lesson—the happy ending that came more than twenty years after the 1878 outbreak, when Walter Reed and his team discovered that the Aedes aegypti mosquito was the culprit in spreading the disease from person to person. The mosquito connection completely explained the seasonality of yellow fever, since it closely followed the rise and fall of mosquito populations. Mosquitoes also explained the connection between yellow fever and urbanization—the disease was driven purely by population and struck cities merely because they had enough people in close proximity to sustain human-to-mosquito-to-human transmission.

Prior to Reed, others had hypothesized mosquitos were linked, but Reed and his team deserve credit for experimentally demonstrating mosquito transmission. They allowed themselves to be bitten and deliberately infected—tragically killing one member of the team in the process.

Yellow fever continues to kill thousands of people every year in forty-seven places around the world

Linking yellow fever to mosquitos made Walter Reed famous, and his name still adorns a major U.S. medical center outside Washington DC. It also immediately suggested an approach to containing or preventing outbreaks through "vector control" by eliminating pools of standing water that could be mosquito breeding sites. That approach, along with vaccines, is still a frontline prevention method used today in the forty-seven places where yellow fever continues to infect and kill thousands of people every year.

We don't yet know who will be the Walter Reed of today who will lead the science to solve the coronavirus problem, but in the end, what the New Orleans yellow fever outbreak of 1878 shows more than anything is that an eventual elimination of COVID-19 is a real possibility. And hopefully, as the news of successful phase 1 trials of coronavirus vaccines this month would seem to suggest, it won't take twenty years.